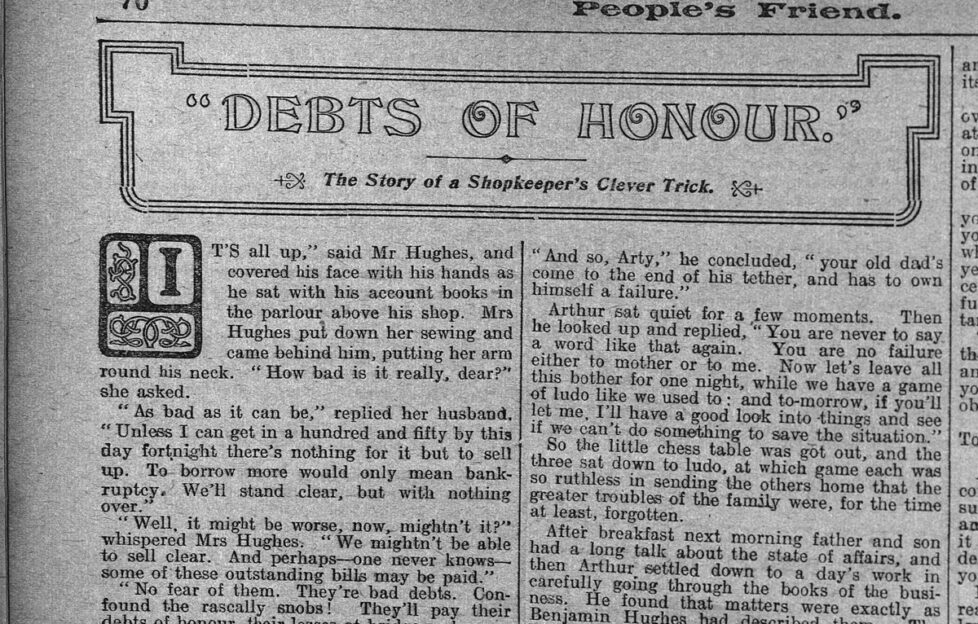

Our latest Reading Between The Lines podcast short story episode is “Debts of Honour” by Humphrey Chalmers, first published in 1913. Read along with the story below and listen to see what the team had to say about it!

“It’s all up,” said Mr Hughes, and covered his face with his hands as he sat with his account books in the parlour above his shop. Mrs Hughes put down her sewing and came behind him, putting her round his neck. “How bad is it really, dear?” she asked.

“As bad as it can be,” replied her husband. “Unless I can get in a hundred and fifty by this day fortnight there’s nothing for it but to sell up. To borrow more would only mean bankruptcy. We’ll stand clear, but with nothing over.”

“Well, it might be worse, now, mightn’t it?” whispered Mrs Hughes. “We mightn’t be able to sell clear. And perhaps—one never knows—some of these outstanding bills may be paid.”

“No fear of them. They’re bad debts. Confound the rascally snobs! They’ll pay their debts of honour, their losses at bridge and races, but the poor tradesman’s bill can wait! And if he presses it’s ‘beastly cheek,’ and ‘insolence’ and they tell one another not to deal with him any more.

“It’s no good, dearie. Nobody taking over the business would give me ten per cent for my book debts. To enforce payment would just ruin a newcomer, and, to tell the truth, half of them could not be enforced, they’ve been standing so long.

“I don’t care so much for myself,” he continued. “But there is you and there’s Arty. He’ll be home for his vacation tomorrow, and I can’t send him back to the University again. He will have to leave without taking his degree.”

“Well, dear,” soothed Mrs Hughes, “you’ve done your best by him. He has had a better education than most young men.”

“I’m afraid it is not much good to him. If he had taken his degree in Commerce he might have dropped into a good situation, but with an unfinished course, who’ll have him?”

“Now sweetheart, don’t look on the dark side. Something will open for Arty, and there will be some little corner for us two old fogies.”

Benjamin Hughes was a furniture dealer in the middling-sized town some thirty miles from London. He had married late in life a woman some ten years his junior. Arthur was their only child, and by dint of many an economy he had been sent to Birmingham University, where he hoped to take the degree in Commerce which is granted by that institution.

The furniture business, however, had been going from bad to worse for a considerable number of years. If the truth must be told, Benjamin Hughes had grown rather too old for the requirements of present-day trade. He had built up a high-class business in earlier, easier times, but now the competition of the big London houses, with their enormous selections and their free delivery fifty miles from town, had taken his best trade from him.

The only business he now did in high-class goods was with those whose chief requirement was long credit; and that was far from being a profitable line for Mr Hughes. Arthur had repeatedly advised his father to go in for a more popular type of business on a cash basis, but Benjamin was too old to change, even if he had been able to raise the necessary capital.

And so the end had come. But how was Arthur to be met on the morrow? The young man was keen upon his studies, and his hopes of distinction at the close of his next session were high. It would be a terrible blow to find that there would be no next session for him.

But there was no help for it, and so, when he arrived the next day, he soon guessed from his father’s constraint and the traces of tears on his mother’s face that there was something sadly wrong.

After tea the story was told, the voice of old Benjamin frequently breaking in the telling. “And so, Arty,” he concluded, “your old dad’s come to the end of his tether, and has to own himself a failure.”

Arthur sat quiet for a few moments. Then he looked up and replied, “You are never to say a word like that again. You are no failure either to mother or to me. Now let’s leave all this bother for one night, while we have a game of ludo like we used to: and tomorrow, if you’ll let me, I’ll have a good look into things and see if we can’t do something to save the situation.”

So the little chess table was got out, and the three sat down to ludo, at which game each was so ruthless in sending the others home that the greater troubles of the family were, for the time at least, forgotten.

After breakfast the next morning father and son had a long talk about the state of affairs, and then Arthur settled down to a day’s work in carefully going through the books of the business. He found that matters were exactly as Benjamin Hughes had described them. The business was only solvent for an immediate winding-up unless the book debts could be got in. But if even fifty per cent of these could be collected it might be possible to launch out on modern lines.

When he had arrived at this conclusion, Arthur sat for a while in deep thought. He had fancied he saw the way out, only he had to reckon with his father, who was too set upon his old ways to agree readily with any revolutionary proposal. He eventually decided to take a bold course.

“Well, what do you think of it?” asked Benjamin as they gathered together round the supper table. “Hopeless, eh?”

“No, I wouldn’t say that,” replied Arthur. “In fact, dad, I think so well of the old firm that I want you to take me into partnership with you. I can’t go back to Birmingham, and I doubt whether I can get any very decent berth for some time. Still, that can wait for a few days. What I want you to do now, dad, is to take mother with you and just run down for a fortnight to Brighton, leaving me in charge. You both need a rest. I’ll mind the shop while you are away, and then when you come back strong and hearty we’ll face the music together.

“And,” he added, “I have an idea it won’t be such a very bad tune after all.”

“But what are you going to do, Arty?”

“Why, mind the shop, as I said.”

“Oh, yes, that’s all very well, but what’s your plan? I hope you’re not going to do anything rash.”

“My dear father, I’ll neither borrow money nor lend it. So much I can tell you. But look here, you’ve spent a lot of money to give me a first-class commercial education. That was an investment, and now the question is: Will you give that investment a chance, or do you think it as bad as these book debts?”

“No but—”

“Now, father, please! I’ll not make things worse, I promise that; but I want a free hand to prove that your money wasn’t quite thrown away at Birmingham.”

With a mother’s simple trust in her only son, Mrs Hughes added her persuasions to those of Arthur, so what could Benjamin do but surrender?

Next morning Arthur stood in the door of the shop and waved his farewell as his parents drove off in a cab to the station. Then he turned and surveyed his charge with all the pride of a young lieutenant when he steps on the bridge to take command of his first torpedo boat. He visited the workshop, directed the assistant in some particulars, and retired into the little glass-walled counting-house for a few minutes, just to revel in the delightful sensation of responsibility.

But he did not stay there long. Emerging, he went upstairs to the house and returned with his typewriter, one of the investments he had made in College. This lie placed on his desk, and after a few minutes’ thought began to tap its keys.

He was a quick typist, but he continued long over his task, and the afternoon found him still at it, with a growing pile of finished letters on one side of him. These epistles differed only in details, so that one may serve for a specimen of all:—

“Dear Madam,—I have the honour to inform you that a friend wishing to make a present to you, has just paid your account of £12 17s 6d, which has been owing to us for four and a half years. In the event of your not desiring to accept this present, we would undertake to refund the money upon the receipt of your remittance. Meanwhile we enclose receipt.

“We are reorganising our business upon thoroughly modern lines, terms strictly cash, and hope to be honoured with continuance of your esteemed patronage.—We remain, your obedient servants, Benjamin Hughes & Son. To the Honourable Georgina Rossiter-Robinson, Warferry Court.”

Arthur paused once or twice and dubiously considered the above signature. “Well,” he assured himself, “It’s only anticipating events; and, anyhow, if the worst comes to the worst, it will help me to take the blame off dad’s shoulders. But, oh, dad wouldn’t your hair curl if you could only see these epistles!”

In the evening Arthur posted all his letters, read a little, and retired to bed. But it was a long time before sleep visited him. With the night watches he began to doubt the wisdom of his action. What if the debtors accepted their supposed presents with thanks?

Even then there would be little harm done, for he quite agreed with his father that ten per cent was a liberal estimate of the value of the book debts of the firm to any possible purchaser of the business. Truly Benjamin Hughes had been very remiss: but then he had been trained in older, quieter, more trustful methods than those of today.

But suppose Arthur had only thrown away that possible ten per cent, what then?

The age of twenty-one is hopeful, confident, optimistic, often too rashness; but at the same time it is, under conducive circumstances, more anxious, brooding, and pessimistic than any other.

So Arthur tossed and fretted as he thought of the possible loss; anon became sleepy, and started broad awake again at the rosy vision of thirty per cent coming in, forty per cent—perhaps even fifty. His father was probably right when he guessed that his debtors—the stars and would-be stars of the rather vulgar local society of the early twentieth century—while utterly careless of the needs of a mere tradesman, would be punctilious in the discharge of their “debts of honour”.

Anyhow, he had done his best to turn these particular trade debts into debts of honour. He must succeed. Of course, he must!

But yet, perhaps he had miscalculated—oh, confound it!

And he would turn over on his other side for a spell.

In the end Arthur slept: for even worry cannot keep twenty one awake for ever. But he rose in the morning to a sense of impending disaster. He could scarcely touch his breakfast as he thought of how at that very moment his letters were probably being opened and read—and perhaps laughed at.

He entered the shop, fidgeted about, knocked over a mirror and broke it, and retired to the counting-house, where he spent two hours of agony trying to read his morning paper; automatically summing up columns in the books, or simply sitting with his elbows on the desk, holding his throbbing head between his palms.

It was just after eleven that things began to happen. A pair-horsed carriage drove up to the door of the shop, and from the counting-house Arthur could discern the figure of the Honourable Georgina Rossiter-Robinson, as usual rather over-dressed, sitting up very straight and stern-looking.

Whilst he was screwing up his courage to go out to the carriage, the footman descended, and, taking a letter from his mistress, entered the shop. Arthur came forward and opened the missive in fear and trembling.

“I am to wait for an answer in writing,” said the footman.

Arthur read—“The Hon. Georgina Rossiter-Robinson is very much annoyed by the impertinent act stated in your communication. She encloses a cheque (post dated ten days) for £21 17s 6d, and will be obliged by a fresh receipt. She also desires to know the name of the person who presumed to insult her in such a disgraceful manner, and wishes to express her surprise and disgust at your permitting it.”

Arthur darted to the counting-house and scribbled a note, which he enclosed in an envelope with the old receipt, and handed to the waiting footman. The note ran:—

Dear Madam,—We have to thank you for your kind remittance. We shall see that the money is refunded to the donor. We regret that, as the donor desired to remain anonymous, we are in honour bound not to disclose his identity. A fresh receipt will be sent you as soon as your cheque has been honoured by the bank. Regretting that we should have been parties to any act of seeming discourtesy, we are, your obedient servants, “Benjamin Hughes & Son.”

As the carriage drove off Arthur hugged himself. This for a start was not bad. But he had not long opportunity for such thoughts before the tumultuous appearance of Captain Raymond Jarette. This gentleman was also in his way a leader. He hunted much, he was President of the two local Coursing Clubs, tot which he annually presented cups for competition. He subscribed to all local sports, and, in fine, cut a big dash in the town and neighbourhood when he was not in Paris or attending races.

He ramped into the shop and roared, “Hughes! Hughes! Where the dickens are you, Hughes?”

Arthur met him. “My father has just gone away for a short holiday, but I shall be glad to do anything for you in his absence.”

“Here!” cried the Captain, producing Arthur’s letter and receipt, “what blank impudence is this? Tell me what double-blanked scoundrel has insulted me, and I’ll horsewhip the dirt cad! Treats me as a beggarly pauper, does he? Here, take your doubly-qualified, filthy money, and be blanked to him and you.”

Arthur picked up the money—some ten pounds—from the table on which it had been flung:— “Many thanks, sir. I hope you will not blame us for your friend’s action. You see, the bill is very long overdue, and we happened to be very short. However, we shall take care that your friend is refunded.”

“Friend be —! Tell me who he is, and I’ll pitch him into the river!”

But Arthur was suavely strong in his obligations in honour not to reveal the name of the payer of the bill, and Captain Jarette had to retire, exuding profanity.

From that time there was a pretty constant succession of irate customers. Some paid cash, some paid cheques, some offered bills at one month, two months, three months; and Arthur accepted them all where there was reasonable security.

But in every case where the payment of cash was deferred he refused to give a fresh receipt in place of the one sent the previous night (which read:— “Received from a friend as a present to So-and-so”) until the money was actually in the hands of his father or himself.

Just as the shop was shut for the night, the evening post came, bringing a budget of letters. Wrathful letters they were, most of them, but a large proportion contained money, and Arthur gloated over his growing heap of cheques and Post Office orders.

Some of the letters sent money on account, promising to pay the remained within a certain time on condition that the anonymous donor had his money instantly refunded. These Arthur put aside for special reply. Others again simply notified acceptance of the gift, with or without thanks, and some of these came from people whose names surprised Arthur.

Still he took the bad with the good, and dwelt for a little while specially upon a pathetic little note requesting him to convey the thanks of the writer to her unknown benefactor. She was a poor widow who eked out a living for herself and family by taking boarders. She had been forced to renew much of her furniture on credit and soft-hearted Benjamin Hughes had really been very lenient with her, allowing her much more credit than business principles would have admitted.

Arthur understood this. “Good old Dad!” he murmured. “I can’t blame you for being kind to Mrs Wilkes. And I think you’ll forgive me for letting her off altogether.”

He set himself to count up the day’s gains. In cash, cheques, money orders and negotiable bills he had already netted thirty per cent of the outstanding debts.

“What a blessed thing is a sense of honour!” he observed as he turned to reconsider the promises and appraise their value.

Then he sat down to compose a letter to his father:—

“Dear Dad,—I’ve been collecting some of your worst book debts. Up to the present I have been pretty successful. I enclose a number of bills I have accepted. Please endorse them and return, and I’ll get the bank to discount them at once. If I can see aright we shall be well out of the wood in a few days.

“Now don’t come home yet. Get all the good you can out of your holiday, and please trust me a little bit longer. Hoorah for the Commercial Department of Brum! Love to mums— Your loving son, “Arthur Hughes.”

Arthur again slept badly over night, but this time it was because of sheer gladness of heart. He had really done a service for his father and was showing that he was fit for something, after all the money spent on his education.

The following day was a repetition of the one before it, and brought in another twenty per cent of the outstanding money. After that things became quieter, but when, at the end of a week, Arthur wrote to his father announcing that he had realised seventy-five per cent, Benjamin wired that he was coming home to see the miracle-worker.

He arrived with Mrs Hughes just in time to find Mrs Delame Burtenshaw, one of his most hopeless customers, paying in full an account which had been kept going for many years by small payments, which were always negatived by fresh purchases.

Up until then he had scarcely believed his good fortune, but after that he could believe anything. But when Arthur showed him the bank book, and the cheques, orders and cash still waiting to be paid in, he broke down.

“The old business is saved!” he sobbed. “Thank God for Arty!”

Later in the evening he laughed long as he heard the story of how the money had been secured. “But,” he objected at last, “what are we to do next? Our market with these people is spoiled.”

“I’m not so sure of that,” said Arthur. “Anyhow it didn’t pay on the old lines, and they’re all warned it’s to be cash now. But we’ve capital to go in for a new line altogether—more popular and so on. Let me help you, dad, and we’ll see.”

“You’ve earned a partnership I guess, Arty,” said Benjamin. “And if you don’t mind beginning with a poor business of this sort after college you can run it your own way.”

And so it was done and the firm of Benjamin Hughes & Son is now the most prosperous both on popular and high-class lines in the home counties.

Catch up with Reading Between The Lines news and previous stories.