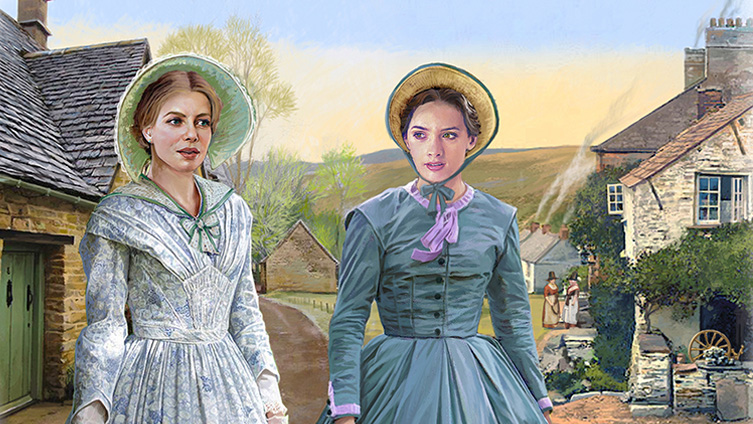

The Bidding Wedding

The fun and frivolity surrounding this Welsh tradition was too much for Harriet to bear...

Illustration: André Leonard.

Subscribe to The People’s Friend! Click here

The fun and frivolity surrounding this Welsh tradition was too much for Harriet to bear...

Illustration: André Leonard.

A ROMANTIC SHORT STORY BY ALISON CARTER

This short story, set in the 1830s, The fun and frivolity surrounding this Welsh tradition was too much for Harriet to bear…

Mrs Jupp was enjoying her visit to Wales very much. The weather was clear and bright, and it was a pleasure to be with Mrs Jemima Hughes, a friend from her schooldays whom she had not seen in years.

“Another walk would be delightful,” she said to Jemima on the Friday morning.

“The fresh air is doing wonders for my constitution already.”

Harriet Jupp lived in a city, and in 1831 Birmingham was smelly, busy and noisy.

Staying with Jemima was making her think that she might persuade Mr Jupp to ask the bishop for a country parish, so they could move somewhere nicer.

The pace of life here was pleasant, and the people (all of them farming stock) appeared to be godly and – on the whole – humble in their manner and attitude.

“We will walk to the little wood up the hill,” Jemima said.

“The lane is well made and I can show you the cottages along the way.”

Jemima was well-to-do. She had married a landowner’s son and had moved to this rural estate when he inherited.

Mr Hughes, Jemima said, employed many of the people whose cottages they would walk past.

“But not all of them are your husband’s workers?” Harriet asked as they passed the first cottage.

“Oh, by no means,” Jemima replied. “Many have a plot of their own.”

“Subsistence farming? My goodness, that is a hard life.”

Harriet had heard from her friend, over dinner the evening before, that a poorhouse was about to open in the nearby town.

She immediately made a subscription to it – she had a strong inclination towards charity and liked to do what she could to assist the deserving poor.

The new superintendent of the poorhouse, also a dinner guest at the Hughes home, had assured her that they were all deserving.

They stopped to take a breath on their walk as the lane began to slope up.

As they stood there, a young man strode up to one of the cottages and stood outside its tiny yard.

“There’s a pole across the gate,” Harriet remarked.

“What could possess anyone to lay a pole across a gate so no-one can enter?”

Jemima had no time to answer, because the young man let out a great shout of fury and three other young men, all in the same farm labourer clothes as the first one, ran up as if out of nowhere.

Their heavy boots thundered on the hard earth of the lane.

“Bring out Sioned Jenkins!” the young man shouted.

His friends seemed to find this very funny, and they roared with laughter.

Harriet tried to see into the cottage interior through its tiny front windows, to find out if Sioned Jenkins was within, and if she was safe.

Did the girl have a protector of some kind against these marauders?

Jemima laid a hand on her arm to stop her approaching any further.

The four young men, one after the other, ran at the pole!

It was a solid length of wood and firmly fixed at either side, somehow tethered to the wall.

As they slammed into it, they shouted the first young man’s demand until the pole fractured with a loud splintering sound.

“Come away,” Jemima said cheerfully. “It’s going to rain.”

Jemima was apparently not worried by this extraordinary scene, and Harriet began to wonder if her friend had been bewitched by the people of the south of Wales and was out of her wits.

But she was obliged to walk on, looking back twice to see the front door opening and a family of three coming out to stand in the doorway.

The rain did not come, so that afternoon the two ladies ventured out again to visit the sick persons of the parish.

Jemima did not mention the incident at the cottage, and Harriet decided to let it lie.

She was, after all, there in the capacity of a guest.

They were walking back to the house when Harriet heard the sound of bagpipes.

They followed the sound and it led them down the slope of the same lane they’d walked up that morning, to the same cottage.

The pole had gone, and the piper was standing in the spot where the coarse young man had shouted in so very unseemly a manner.

The pipes signal a wedding

Jemima explained, raising her voice over the music.

Harriet had visited Scotland, and was sure that the pipes she’d heard there had been played with more refinement.

“The tune is ‘Gwenllian’,” Jemima went on. “A famous song about a Welsh hero. It’s merry, don’t you think?”

“Could he play it any quieter?” Harriet asked.

“Goodness, I don’t think so. There’s a wedding in the offing.”

A black-haired older woman came out through the cottage door and laid a tankard on the ground beside the bagpiper.

“I recall that it’s her daughter, Sioned, who is to be married,” Jemima said. “The wedding will most likely be tomorrow.”

“Oh, my! What’s this coming now?” Harriet cried.

Up the lane, accompanied by more noise, came a motley, ill-dressed crew of locals.

They carried old wooden crates, and talked so loudly in Welsh as they approached that Harriet was put in mind of London Zoo, which she had visited with her husband.

They really were raucous, some of them swinging purses at their sides, some of them apparently telling, or responding to, jokes.

It seemed to Harriet that many of them really ought to be engaged in honest labour at this time of day, rather than parading in the streets.

A gaggle of girls and young women pushed to the front of the crowd and entered the house first.

When they came out again, older women and men went in.

It was clear that they were depositing inside the cottage whatever it was that they had brought with them.

The last to go in and come out was an old fellow carrying a close stool! Harriet was appalled.

“That man has a commode in his arms!” she exclaimed to Jemima.

One of the other older men made a coarse joke to his companion about the commode, and in English.

Harriet understood it, and decided that it was time to leave.

As they walked along the lane, Jemima explained that similar things would be going on at the cottage of the bridegroom’s family.

Harriet actually heard her laugh!

“It will be more noisy over there,” Jemima explained, “because of it being lads, the friends and family of the groom.

“There may be ale at the groom’s house.”

Harriet was finding it impossible to countenance this behaviour.

How had cavorting like this become the norm before a wedding in Wales?

She had never seen anything like it. A marriage was a momentous thing.

Her marriage to Mr Jupp had been suitably solemn, with a lot of organ music.

There had been a period of sober, quiet reflection before the big day, not an appearance of the Lord of Misrule!

“But in chapel tomorrow?” she asked Jemima nervously. “Surely in chapel . . .?”

“Oh, there’ll be no bagpipes in chapel,” Jemima assured her with a laugh. “No close stools, either, God willing.”

The following morning, Jemima was eager to get breakfast finished.

She wanted to take her friend into the village.

“You see, a wedding here has a lot of . . .” Jemima frowned, searching for a word.

“Perhaps I should not call it ‘ceremony’, but certainly busyness.

“Come, Harriet – I’ve sent the maid for our cloaks. We have to set off.”

Back to the lane they went, Harriet unwillingly.

The antics of these country people were worrying her.

What would Mr Jupp make of the shouting of demands at the doors of innocent girls and what the locals chose to call wedding presents?

The young man that Harriet now knew was the groom was there again.

He was a muscular, bold-looking person with flashing eyes.

Just after they arrived on the scene, he began to call out again.

“Rhodri Evans demands to take Sioned Jenkins to chapel!”

He was banging on the window. His friends, lounging against nearby walls, thought it most amusing.

“I want the hand of Sioned Jenkins in marriage!” the bridegroom yelled.

Then the most bizarre thing that Harriet had ever seen occurred.

The door opened and out came seven or eight women and girls, all with their hands pressed over their faces and bonnets low over their brows.

They arranged themselves to stand in a row – a difficult operation because none of them could see a thing.

Beside Harriet, Jemima smiled with satisfaction.

“They mean to deceive him about which is his bride. Observe.”

“They mean what?” Harriet cried.

The young man stamped up and down the line of girls and peered at them for a minute or so.

Giggling was heard.

Jemima began to bounce up and down on the soles of her feet.

“Oh, but he is more deceived even than that!” she exclaimed. “Look yonder!”

A horse, or rather a scrappy, lumbering old pony, emerged from behind the row of cottages, entering the lane further along.

On its back sat another young man that Harriet hadn’t seen before. Behind him, clinging on, was a girl.

“Sioned!” the bridegroom bellowed.

His friends scattered, shouting commands at each other to set off in pursuit, and a minute later another pony and a horse were hurtling after them, two men on each beast.

“They will bring her back, be sure of it,” Jemima said.

She had taken a seat on a low stone wall just as if this were a play.

“This is an abduction?” Harriet said, horrified. “And on the girl’s wedding day! Who is that criminal on the horse?”

Jemima laughed.

“That’s William Jenkins, brother of Sioned. He has no pony, so I think he’s borrowed it from Rhodri.”

“But isn’t Rhodri the groom?”

Harriet sat down heavily on the wall beside her friend. She was flummoxed, silent and appalled.

A quarter of an hour later the party returned: all three horses, the youths and the girl that Jemima claimed was to be a bride.

They dismounted and William Jenkins, his arm around his sister’s shoulders, spoke.

I’m a fool. I forgot to say the bit about virtue.

“At last,” Harriet said under her breath. “Some sanity, some Christian probity!”

William drew in his breath and began to speak in as big a voice as he could manage.

“Sioned Jenkins is a woman of great virtue and is not to be obtained except by one who proves himself worthy of her hand.”

All the men present heartily agreed that Rhodri Evans fitted the bill and Sioned went indoors.

The men were heard to say that they had onion crops to dig up, and they dispersed.

Jemima took Harriet back for luncheon.

“It is a game,” she said as they walked. “A celebration and a tradition.

“The groom must win the bride, and the bride’s family must not let her go easily because she’s precious to them.”

“It’s preposterous,” Harriet grumbled. “I need several cups of strong tea.”

Harriet did not want to go to the chapel to see the wedding that afternoon.

She suspected that every pious bone in her body would be offended by whatever might occur.

Jemima said she must.

“You have come this far in witnessing a bidding wedding,” Jemima insisted. “You must see it through.”

“And what, pray, is a bidding wedding?”

“I’ll tell you all about it afterwards. Fetch your gloves; it will be cold.”

The wedding madness continued outside the chapel, with Sioned’s father and brothers laying ropes across the pathway and making guests pay a penny to pass.

“The pennies are for the happy couple as they start out in life,” Jemima explained.

They stood at the back of the chapel.

Harriet was relieved when the minister conducted a proper marriage ceremony before a more-or-less hushed congregation.

But as soon as everyone was out in the light of day again, the bridegroom was handed the reins of the same scrappy pony.

He hauled his wife up behind him and galloped off with his friends running along behind in the most raucous manner.

Harriet went home with her hosts feeling exhausted by it all. She considered going home early if transport could be secured.

But Sunday, the following day, was blessedly peaceful, with two sedate church services and some reading to calm her down.

On Monday morning, Jemima’s maid was heard in the hallway enthusing about a hand mirror that she had purchased “from the Jenkins bidding”.

Harriet could not help asking Jemima the meaning of this.

“It’s simple,” Jemima replied. “After the wedding, unwanted items may be sold. Sioned Evans must own a mirror already.”

Seeing Harriet’s expression of bemusement, she sat her down with another cup of tea.

“It is a firm and long-held tradition here.

“When a young couple marry they own very little and have low earnings, so everyone expects to contribute.

“A ‘bidder’ goes from house to house inviting folk to the wedding.

“He further asks guests to bring goods or small sums of money for the welfare of the couple.”

“I see.” Harriet nodded.

“Sometimes he carries printed invitations, though more often the words are simply spoken at the door.

“The final thing he asks is that guests should return, as their wedding gift, items and money given to them in the past by the families now holding a wedding.”

Harriet was trying hard to keep up.

Jemima thought for a moment.

“It is a practical system. These offerings form a loan, one might say, with no interest payable.

The loan is agreed and arranged by a whole community, over generations, repeating with each new marriage.

“For instance, Mrs Jenkins, Sioned’s mother, will have given a blanket, a pan or a bucket at a wedding five years ago, and now it is the turn of that older, more settled bride or groom to give back.”

Jemima laughed.

“The fun and frolics are a chance for people with hard lives to enjoy themselves,” she finished.

“There is so much levity, Jemima, when a marriage should be taken seriously,” Harriet protested.

“Examine these traditions and you will see the seriousness they show,” Jemima countered.

“The bride’s family signal their love for their girl when they pretend to keep her from the groom.

“The groom signals his devotion by seeking her out. You see?”

Harriet was beginning to see. She thought about the stream of presents, all from people’s own homes, flowing into the cottage.

Then she thought about the donation she had made to the poorhouse.

It was easy to make, and it kept her at a distance from the recipients of her money.

“May I give the couple something?” she asked.

Jemima was surprised and delighted.

She said they should walk that very day to the new couple’s cottage.

Harriet prepared a little purse of coins and gave it to Sioned Evans when the door was opened.

Sioned seemed unsurprised by the gift, though surprised at the giver, a stranger.

Her husband came up behind her.

“I will fetch the paper that all the gifts have been written on,” he said.

“Neither of us is much good with figures, so perhaps Mrs Hughes can help record the lady’s kind gift.”

“The paper?” Harriet asked.

“Every gift is recorded,” Jemima explained.

“These little records are stored in every house. A bidding wedding is a very particular sort of wedding.”

Harriet raised a hand.

“You must not trouble to make a note of what I gave. I’m visiting from the city.”

“Then you must come in,” Sioned Evans said firmly.

“If you live a distance away I must beg you to write down your address so the gift can be returned when the chance comes.”

“We have spiced ale left over from the party yesterday,” Rhodri said as they entered.

They drank, and Harriet obediently wrote her name and address on their paper.

I have learned a good deal about weddings here

she told them.

The couple showed them what had been donated, and Sioned explained that nobody minded if an item was sold on.

“The purpose is to set us on our feet,” she said, and she smiled at Rhodri.

“We will never forget the presents, and everything will be offered back when the time is right.”

She looked at Harriet.

“I hope you understand that our traditions are honourable.”

Rhodri took her hand.

“We have little, but we are proud people, and loyal to one another.”

“I can see that.” Harriet smiled. “When I return home I will tell my husband all about it.

“Your remarkable customs will be of great interest to him.”

They went on their way, and Harriet packed for home the next day.

She promised to come and visit Jemima again.

“I expect there is more to learn,” she mused.

“Yes, there certainly is,” Jemima agreed

Enjoy exclusive short stories every week inside the pages of “The People’s Friend”. On sale every Wednesday.

Alison Carter

Teresa Ashby

Beth Watson

Alyson Hilbourne

Katie Ashmore

Kate Hogan

Liz Filleul

Beth Watson

Alison Carter

Sharon Haston

Kate Finnemore