Picturing The Future

Jinnie couldn't believe Hubert would want to take a photo of a lowly laundry maid...

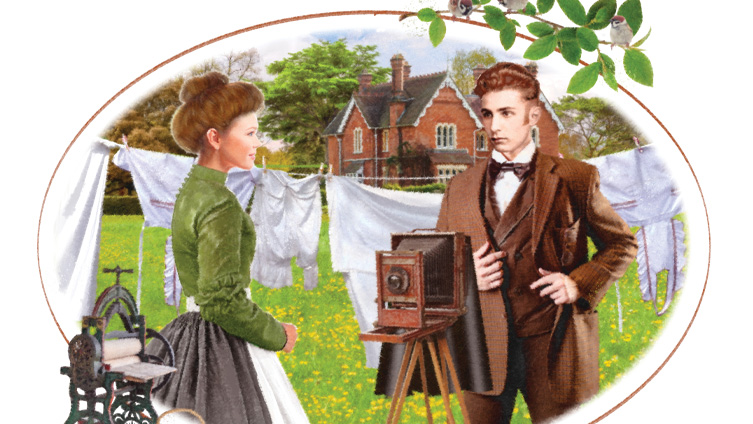

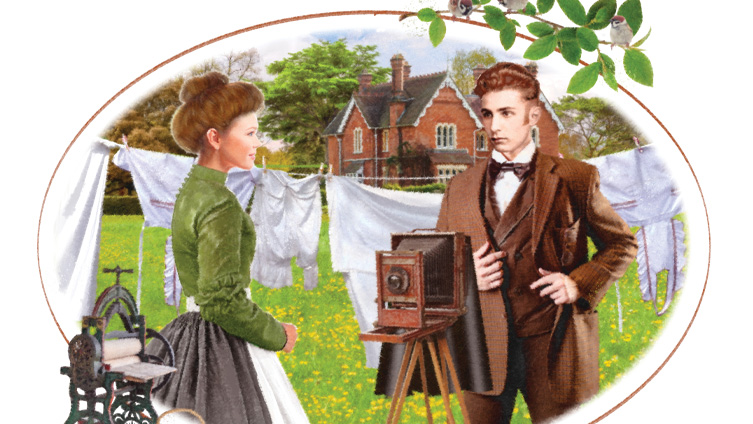

Illustration: Mandy Dixon

Subscribe to The People’s Friend! Click here

Jinnie couldn't believe Hubert would want to take a photo of a lowly laundry maid...

Illustration: Mandy Dixon

HISTORICAL SHORT STORY BY BECCA ROBIN

In this story, set in 1901, Jinnie couldn’t believe Hubert would want to take a photo of a lowly laundry maid…

Jinnie was uncomfortable and wasn’t sure she could hold her position much longer.

Sitting on the bottom of the flight of stone steps leading up to the hall’s main entrance, the lumpy gravel was digging into her ankles and pins and needles were starting to spread.

The Amberton Estate was large and there were a great many to fit into this picture.

Mr Richey, the photographer, had positioned his camera a fair way off.

As well as the indoor housemaids, footmen and kitchen staff, there were also outdoor workers, such as the gardeners, gamekeeper and chauffeur.

As a laundry maid who spent her time in an outhouse, Jinnie didn’t feel she fitted in particularly well with either group.

She took a quick glance around.

From where she sat, she couldn’t see Lord and Lady Parrish at the top of the steps, but could just spot the fancy bird wing hat of their daughter, Lady Venetia.

Unfortunately, as she was looking, Jinnie caught the outraged eye of Mrs Pring, the housekeeper. She quickly turned back to face the camera.

Mr Richey was making his last-minute adjustments. Mr Ferris, the chauffeur, had collected him that morning from his new portrait studio in the town’s high street.

It was important to take this group photograph while the newly laundered staff uniforms were still clean and tidy.

The family portraits would be taken later, doubtless in the hall’s grandest rooms, some of which Jinnie had never set foot in.

Although Mr Richey was young, he clearly knew what he was about. He stepped back and cast his shrewd eye over them all.

“Perfect,” he said in his pleasant, clear voice. “Please stay very still until I say you can move again.”

He disappeared beneath the black cloth shrouding the back of the wooden box on legs.

As he turned a knob, the concertina front went in and out as though the machine were breathing.

By contrast, Jinnie was almost too afraid to breathe. Imagine the terrible telling-off she would get if she ruined this photograph which had taken so long to organise.

Apparently, the slightest movement would cause the image to blur.

From the corner of her eye, she could see that her hands were clearly in view, resting on the folds of her skirt.

She wished she had thought to hide them, but it was too late now.

Though she was only eighteen, Jinnie had the hands of an old woman, her bulging knuckles raw from scrubbing and wringing wet clothes.

Mr Richey re-emerged from beneath the cloth and pulled out a section at the side of the camera.

He nodded with a broad smile, a signal that he was ready to take the photograph.

He removed the cap, uncovering the glass eye, and replaced it after a bare couple of seconds.

Jinnie could hardly believe that after all the preparations, it was all over with so little fanfare.

In bright sunshine, that’s all the exposure necessary

Mr Richey explained.

He did take one more photograph of the group as an insurance, since the glass plates he used were easily broken and would need transporting to his studio to be developed.

The sitting over, the group began to break up.

“Time to get back to work,” Dora the under parlourmaid barked, as though it was usual for Jinnie to shirk from her tasks.

“I know,” Jinnie snapped back. She hadn’t meant to, but the unusual events had distracted her from her usual stance of ignoring Dora’s attempts at bullying.

Little did Dora know that Jinnie had endured far worse, growing up as she had in the workhouse.

“You take care, my girl,” Dora warned.

Jinnie rose to her feet and stared her in the eye. A little less certainly, Dora carried on.

“Any more cheek from you and I’ll be telling Mrs Pring.”

Jinnie, who was good at staying out of trouble, lowered her eyes.

Believing her point had been scored, Dora flounced off with her best lace apron strings flying; apron strings which Jinnie had ironed.

Jinnie looked down at her old green blouse, grey skirt and plain white apron. No lace for her.

Mrs Pring had insisted that for the photograph she should wear her hated white mob cap, which she always removed when working because it made her head sweat.

As she turned down the path leading to the outhouses, she took one last look at Mr Richey.

The photographer was very handsome, clean shaven and with dark auburn waves in his hair, but it was his smile which had set the parlour maids ooh-ing and aah-ing.

There was no-one for Jinnie to gossip with, but she wasn’t sure she even wanted to.

Jinnie was a realist. It wasn’t wise for someone like her, someone without any family and in the lowliest kind of job, to engage in silly daydreams about a young man she was never likely to see again.

On Mondays and Tuesdays, a young girl called Hannah came up from the village to help in the laundry and Jinnie enjoyed the company.

She had been the same age when she’d first come to help old Mrs Tulliver, who had since passed away.

Today was a Thursday, and not only was Jinnie on her own, she was also behind in her usual routine due to all the aprons she’d been washing, starching and ironing in readiness for the photograph.

Consequently, twice as much washing awaited her as she would normally have done that day.

There were sheets and towels but mostly it was shirts and underclothes, along with a few dainty blouses belonging to Lady Venetia, which required special attention.

It had all been soaking overnight in two large tubs of soapy water but once scrubbed, the underclothes and white shirts would need to be boiled in the wash copper which Jinnie had already filled with water from the well.

Her first job was to build up the fire beneath the copper to get it boiling, while she separated out the washing that only required a light scrubbing and rinsing.

It was a beautiful sunny day so she would do as much as she could out of doors, away from the steamy laundry.

The mangle was ready and waiting in the little yard with the wooden bucket in front to catch the water.

Once they were pegged out, the clothes would dry quickly, which meant she could get on with some ironing in the late afternoon and hopefully catch up a bit.

By lunchtime, she had made good progress and a line of washing was drying nicely in the buttercup-strewn meadow beside the outhouses.

She asked the gardener’s boy to keep an eye on the boiling copper while she went to the kitchen for food.

A couple of the maids were still giggling over Mr Richey, who, from what Jinnie could gather, had asked to photograph them.

At least that was what they said, if they could be believed.

By three o’clock, Jinnie was back at work, pegging out the last lot of underclothes, when there was a polite cough behind her.

She turned and there he was, Mr Richey, smiling and with his hand outstretched.

Quite scandalously, he was holding the folded, flat pair of bloomers she had just run through the mangle.

“They must have fallen from the pile,” he said. “I found them on the grass.”

Jinnie blushed and stammered out an apology as she tossed the bloomers into her pegging-out basket.

Mr Richey leaned against the gatepost, folded his arms and continued surveying the scene.

She couldn’t carry on with her work, as she felt compelled to hide her red raw hands behind her back.

“I’m sorry if I embarrassed you,” he said.

“I finished taking the family’s photographs earlier, but I am interested in taking other kinds of photographs. Portraits of ordinary people at work.

“His lordship said I might take a few. Would you mind if I took one of you, pegging out the clothes?”

Surely not the bloomers!

Jinnie blurted out before she could stop herself.

Mr Richey looked shocked by her outburst. She clapped her hand to her mouth but then he began to laugh.

After the laughter died down, she found she was still smiling at him.

That was all right because he was still smiling at her, and his eyes were twinkling.

He asked her to go about her work while he set up his camera.

He placed it in front of one section of the clothes-line which zig-zagged across the small meadow.

The washing looked like a maze of flags of different shapes and sizes, but there wasn’t a breath of a breeze and it all hung still.

“The graceful way you move behind the sheets, you look for all the world like a puppet Cinderella in a shadow show,” he observed.

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen one, sir.”

“Please don’t call me sir, call me Hubert,” he said. “May I know your name?”

“Jinnie,” she said, flustered again.

He continued to chat pleasantly. She guessed he was trying to put her at ease.

She tried her best to carry on naturally and not feel too self-conscious while he studied her movements,

“Actually, were you about to take this one down, Jinnie?” He gestured towards the nearest sheet.

“It is dry, Hubert,” she said, trying out his name.

“Then can you stretch up to remove the pegs and – there – hold that position please.”

It was extraordinary. Fancy someone thinking that such an ordinary, everyday activity was worthy of being photographed.

She froze, looking up at her hands removing the pegs, the way he wanted.

For a moment, she thought she saw what he could see and, suddenly, she didn’t feel ashamed of the way they looked any more.

They were strong, capable hands caught in the act of removing the beautifully clean sheet, against a backdrop of clear blue sky.

Not that the photograph would pick up any of the colours, but she would always recall them.

Already, she knew she would always remember this moment.

“Thank you, Jinnie,” he said at last. “That was excellent and I managed to capture your sweet smile.

“I must go now, to catch a lift back to town with

Mr Ferris.

“Your photograph will be among the official ones I’ll send over in a few days. I hope you’ll like it.”

He waved at the gate and she waved back. Her heart was nearly exploding.

She had never been looked at or spoken to in the lovely, gentle way Hubert Richey had looked at and spoken to her.

Even if they never met again, at least she could cherish the memory of this perfect day in years to come.

Jinnie’s head was in a spin all weekend.

On Monday morning, Mr Ferris went to pick up the photographs, and at lunchtime, the one of the entire household on the front steps was brought to the kitchen for the staff to see.

It was framed, ready for the library wall.

Nobody in the group was smiling. There sat Jinnie on the lowest step, looking small and miserable in her dreadful mob cap.

It didn’t matter, because this wasn’t the photograph she was longing to see.

“What about the others?” Jinnie seldom spoke out in the busy kitchen and the room quietened.

“What others?” Dora said scornfully.

“Mr Richey took other photographs of some of us at work. He took one of me out in the meadow, with the washing drying on the line.”

There were titters around the room, but at the same time she noticed how the maids who had boasted of having had their own portraits taken were both looking thoroughly miserable.

“A photograph of you with the washing,” Mrs Pring said mockingly.

“His lordship couldn’t make out why Mr Richey would want to waste his time.

“If you must know, those other photographs helped start the fire in the drawing-room this morning, and if you ask me, that’s the best use anyone would have for them.”

Jinnie felt as though she had been punched. She couldn’t speak or look at any of them but could imagine Dora’s cruel eyes glinting with merriment at her distress.

She turned and ran from the kitchen and didn’t stop until she was back in the laundry, where she sat on the old stool, buried her face in her apron and wept.

On Sunday afternoon, Jinnie was standing on the pavement outside the photographer’s studio in the high street.

It was six miles’ walk from Amberton Hall to town, but this was her afternoon off.

Of course, the studio wasn’t open, but she was wondering if there was a chance she might spot her photograph on display inside.

The bow window gave a good view and she pressed her face up against the glass, screening out the sharp sunlight with her hands.

The walls were covered floor to ceiling with sepia-tinted photographs.

Most were formal portraits and family groupings, but there were also landscapes with castles, mountains and lakes.

Jinnie started on one side and worked her way around, but her own picture was nowhere to be seen.

She stepped back, disheartened.

Above the window, the name Hubert Richey shone in flourishing, freshly painted gilt letters.

It shone the way the photographer himself did, in her memory.

Then she noticed the card resting against the bottom of the window. Jinnie was able to read and write a little and could make out the words: Assistant Required. Apply Within.

There didn’t seem any point in hanging around, but Jinnie froze as she heard a polite little cough behind her, surely one she’d heard before.

She spun round.

“Hubert!” she cried.

He frowned a moment, perhaps thrown by her Sunday hat. Quick as a flash, she undid the ribbon and removed it.

“Jinnie!” he said with pleasure. “What are you doing here?

Did you like the picture I took of you? I think it’s one of my best ever.

“Oh, Hubert, I haven’t seen it yet.”

A flicker in his eyes acknowledged her tone of despair. He produced a key from his pocket and let them into the premises.

“Well, never mind, I have a copy. In fact, I was only admiring it this morning.

“Then I went for a walk and happened to go further than planned.

“Did you walk from the hall? It’s quite a way.”

“Yes, I did.” Jinnie replied.

“Well, what a treat. I don’t get many visitors.” He smiled at her.

“I live above the shop, so to speak. If you’d like to wait, I could go and make us some tea?”

Jinnie thanked him.

He led her through the first room and into a room of a similar size, which was clearly where he had taken the portraits she’d seen on display.

At one end there was a chaise longue and behind it, a brown velvet tasselled curtain, swept up on one side in generous folds.

Hubert’s camera was set up opposite, on its stand. Against the side wall were other chairs and a small table bearing an aspidistra plant.

Hubert left to make the tea but Jinnie was too excited to sit down.

She walked around, too scared to touch anything but admiring everything.

She approached the table in the corner and at first didn’t recognise the photograph lying there.

It was of a very pretty girl with unkempt hair, taken from the waist up and a slightly low angle.

She had a dimpled smile, and her arms were raised as she unpegged the corner of a white sheet from a washing line.

“Ah, you’ve seen it.” Hubert had appeared again. “You photograph well, if you don’t mind my saying so.”

Jinnie shook her head to show she didn’t mind.

For the moment, she couldn’t speak. She was afraid if she did, tears would start to fall.

Hubert poured the tea and suddenly it all came out in a rush, the reason she had not seen the portrait he had sent to the hall.

Hubert shook his head.

“Real beauty is lost upon some people,” he said simply.

Having been revived by the tea, Jinnie realised she was about to say what she had been thinking of saying since seeing the card in the window.

“May I apply for the position of assistant?”

“Do you know what it entails?” he asked.

“Not really, but I have always had to look after myself in life, Hubert, and I am a quick learner.”

“I believe you.”

What a relief to find him taking her proposal seriously.

“It will involve minding the studio while I am out, keeping it clean and dealing with the public.

“I also need someone careful I can train up to help develop the plates.

“Do you have any days off from your work at the hall?”

“One day a month and it’s due this Friday.” Hope was rising in her heart. “I could come and spend the day here, as a try out?”

“That would suit very well. And by the by, the boarding house two doors down is very respectable and I know they have a vacancy.”

Hubert smiled, and although it might have been too early, clinked the edge of his teacup against hers.

Here’s to my new assistant.

They talked for another hour, until the time came for her to head back to the hall.

They shook hands and Hubert said he would look forward to seeing her on Friday.

It was a glorious afternoon, one that could well make Jinnie believe that nature takes care of her own.

The fields and hedgerows were a riotous show of wildflowers in bloom.

All around, the birds were singing their hearts out, and Jinnie’s heart was singing along with them.

Never miss an issue ‘The People’s Friend’ packed with even more stories on sale every Wednesday.

Paula Williams

Deborah Siepmann

Alison Carter

Teresa Ashby

Beth Watson

Alyson Hilbourne

Katie Ashmore

Kate Hogan

Liz Filleul

Beth Watson