Parachute Silk

Lesley and I weren't the only ones who found ourselves drawn to the fluttering material...

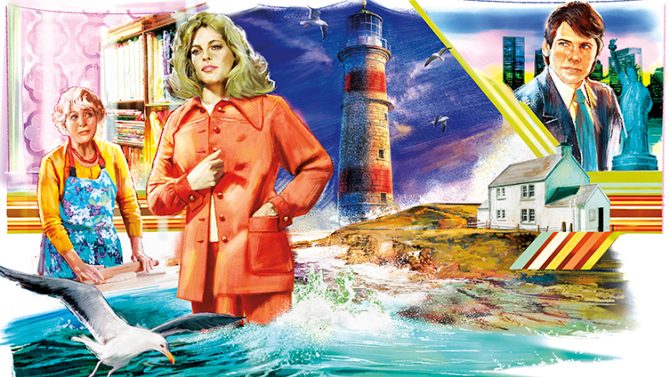

Illustration: Sailesh Thakrar.

Subscribe to The People’s Friend! Click here

Lesley and I weren't the only ones who found ourselves drawn to the fluttering material...

Illustration: Sailesh Thakrar.

HISTORICAL SHORT STORY JESSMA CARTER

In this story, set in 1944, Lesley and I weren’t the only ones who found ourselves drawn to the fluttering material…

My name is Maggie Strachan, and I grew up in a small town on the east coast of Scotland.

We could see Edinburgh from the beach, so we felt we were in touch with a bigger, grander world. But the war changed all that.

It was 1944, and many of the young men who would have become fishermen or miners or worked in the linoleum factories were now doing military service.

My mother died when I was still an infant and my minister father did his best.

He had a hard time persuading me to stay on at school and sit my exams.

He had tried before to encourage me to do things like piano playing or swimming, neither of which I excelled at or enjoyed, but he was adamant that I should get some qualifications for university.

“Women’s lives are going to change for good after the war, believe me,” he said. “You’ll get a chance to be doing things women never did before.”

I was reluctant, but wanted please him.

However, had I known that Lesley Armitage would join our class, I would have shown more enthusiasm.

Lesley Armitage had come to school, in a car, with her mother driving no less, just a few days before the summer holidays.

They had moved into a small, rented farm cottage a couple of miles from town and from it there was a wonderful view of the sea and the world beyond.

Little was known about Mrs Armitage and her daughter.

But our village was no different from any other.

Someone knew someone who knew someone who could tell you a thing or two about the Armitage family.

Right enough, there had been a divorce and Mr Armitage had left his wife for a younger woman.

Sympathy veered towards Mrs Armitage in the town talk – but then, you never know, do you?

No-one, however, disputed that Mrs Armitage was a beauty.

She seemed shy. Her smile was hesitant, her skin smooth and pale.

There was a look of loss, of sadness, about her.

While folk spoke to her, muttering an encouraging “Good morning” as she passed, she rarely stopped to talk.

Even then, it was usually a brief comment on the weather or an enquiry about where was the best place to go for firewood and a polite “Thank you”.

Sometimes she smiled and said she was glad to see the sun was out.

“Nonetheless,” folk said, “divorce is no’ just the best thing when you have a family.”

Others, as always, pretended charity.

“We don’t know the circumstances, do we?” they said, their eyes gleaming with curiosity.

On first glance, I knew that I would like Lesley.

She had very definite brown eyes.

There was no need for her to say that she found something interesting, puzzling or amusing; her eyes would show it.

“So you know one another, do you?” old Mr Sinclair asked, when we first met in his classroom, to learn about the Romans and their language.

“We soon will,” Lesley said.

She always seemed to be on the verge of being cheeky, and then withdrew just in time.

Don’t you think we’d do better with lots of gods like the Romans had, sir?

she’d ask.

Sometimes she’d ask about their clothing.

“Don’t you think that the togas the men wear are very like women’s clothes today?”

Sometimes she questioned their diet.

“Does the word panis, for bread, mean that it’s like a pan loaf, sir?”

Lesley was relentless in her questioning in a way that couldn’t have happened in a larger class.

“I don’t like the way they watched men fight to the death, and then called it a circus, do you?” she’d say.

I liked Lesley. I liked her openness, and the way she talked to everybody, as if they were all equal. I liked her opinions. I liked the way she voiced her doubts.

Often, after school, we’d walk up to her cottage. We sat outside on a bench, facing the sun and the sea, looking down to the village, and talked.

Occasionally, her mother would appear and potter around the garden.

It felt, as I look back on it, that that summer went on for ever, and that war was far away.

By late September, Lesley and I had been in class together for more than a month.

We were sitting lazily outside her cottage when, suddenly, there was a loud screeching in the sky.

It became louder and louder so that we had to cover our ears and rush inside to stop the pain.

Then there was a frightening crash and an eerie silence.

Even the birds stopped calling.

A small aeroplane was on the ground about half a mile away. Inside the house we could sense the heat of the flames and see the smoke rise into the air.

When the smoke lessened we saw a beautiful sight borne on the wind towards us, and then falling slowly to the ground.

The sun caught its silvery glow.

It was like a huge umbrella, gold and silver and pale blue, shimmering, shaking and folding itself into an untidy bundle near where we had been sitting.

Lesley was, of course, the first to have the courage to go out and have a look.

“It’s a parachute!” she called to me.

It’s the most beautiful silk.

She was fondling the material, lifting it up, letting it flow through her fingers.

I went nearer, but slowly.

I had been unnerved by the curious shape falling to the ground and the sudden silence.

The parachute lay untidily, still fluttering, bulkier than it had looked in the sky.

Some of it had been caught in gorse bushes.

I could see a hand reaching out from beneath the untidy bundle.

Lesley and I exchanged a shocked look.

It must have been two hours later that we heard the sound of voices from the other side of the hill.

They came within sight and shouted out, “Did you see it? The parachute?”

There was a group of women, maybe seven or eight, slightly breathless, excited and curious, their eyes greedy.

We stood, Lesley, her mother and myself, outside the door of the cottage.

The sun was bright, and we had to shade our eyes with our hands.

“Can I help you?” Mrs Armitage asked.

The women stopped, for there was something disapproving in Mrs Armitage’s voice.

“We thought as how somebody might be needing help,” one of the women replied.

“What made you think that?” Mrs Armitage was cool.

“We saw a parachute come this way when we was down at the harbour.”

“And you came to help?” Mrs Armitage paused. “What help does a parachute need?”

“Maybe there was someone hanging on to it.”

“And was there?” Mrs Armitage was cool.

“Not as we could see. We thought maybe they’d fallen into the sea.”

“The parachute is there!” Mrs Armitage pointed. “Help yourselves! I expect you’ll find a use for the silk.”

She nudged us inside and we watched the women from the window.

They cheerfully packed the parachute as tightly as they could into a portable bundle, tucking in the torn strands carefully.

Then there were the straps and strands of leather to contend with.

It took some time for them to get the parachute into sufficient order to be carried back down the hill.

“Did you notice,” Mrs Armitage asked, “not one of them seems to care about the pilot?”

Then she cried – long, bitter tears. Lesley and I left her alone.

The parachute was the talk of the village.

The women fondled it, laughing and gossiping. It joined them in a kind of sisterhood.

The sun shone all afternoon and the more it shone, the more the parachute glistened, and the more they planned how they could use the silk.

“My mother is German, as you’ve probably guessed,” Lesley told me.

“She met my father when he was on holiday in Germany years ago, so she is British by marriage.

“I had a happy childhood here in Britain, but then the war came.

“A war does things to you that you don’t expect. Good friends became suspicious.

“Mum suffered. Especially with the government keeping an eye on her, like she was some sort of spy or something,” Lesley said fiercely. “As if!”

She stopped talking, although I could sense that she had a lot more to tell.

We decided, the three of us, that we weren’t doing any harm by looking after the pilot ourselves.

He wasn’t seriously hurt, for the parachute had landed silently and softly, but his leg had been twisted in the fall and he was in some pain.

Of course he, Wilhelm, was German – very young, shy and apologetic when he discovered where he was and what had happened.

He was reassured by Mrs Armitage.

It was easy, as it turned out, to keep Wilhelm’s presence a secret.

The police assumed that he had somehow been injured and unable to fasten his parachute securely and had fallen into the sea.

For Lesley and for me, looking after him became a source of great excitement.

We walked up the hill after school and helped nurse and amuse him.

Language was no problem, for Mrs Armitage acted as interpreter.

It was easy to see, however, that as Wilhelm began to get fitter, Mrs Armitage grew more and more uneasy.

I had told nobody, not even my father, about Wilhelm.

I knew that in the sight of the law I was helping to harbour an enemy.

Enemy. It sounded too dreadful even to mention the word.

Wilhelm, too, was becoming uneasy. Soon, surely, somebody would notice something.

“I have an uncle in London,” he told us. “He has been there for many years, working in a hospital. He has become a British citizen.”

It was easy after that.

Mrs Armitage managed to get hold of the uncle on the telephone and let him know that his nephew was safe and well in Scotland and would join him soon in London.

One evening, we went with her in her car to Edinburgh, where Wilhelm could catch the night train to London.

Mrs Armitage gave him several tips on how to behave if anyone spoke to him.

“Pretend to sleep,” she said. “Mutter. Other travellers will be wanting quiet at this time of night. Your uncle says he will wear a blue and white scarf so you’ll know him.”

Back home, and back at school, Lesley and I felt dismal. All the adventure had gone out of our lives.

There was a fashion show at the village hall.

The local WRI had organised it, a display of the many ways old clothes could be turned into new – how to make frocks from curtains, how to turn jackets inside out and then, the climax of the show – what to make from parachute silk.

The garments were indeed beautiful – nightdresses, underskirts, blouses, even a pair of silk knickers.

“I wish we could get hold of another parachute,” I heard the ladies say as they drank tea.

“What happened to the pilot?” one of them asked. “Was he hurt or ever found, do you know?”

They drank more tea.

“It was some mother’s son,” one of them said.

“Right enough. Right enough,” another agreed. “A mother’s a mother, wherever.”

Never miss an issue ‘The People’s Friend’ packed with even more stories on sale every Wednesday.

Paula Williams

Deborah Siepmann

Alison Carter

Teresa Ashby

Beth Watson

Alyson Hilbourne

Katie Ashmore

Kate Hogan

Liz Filleul

Beth Watson