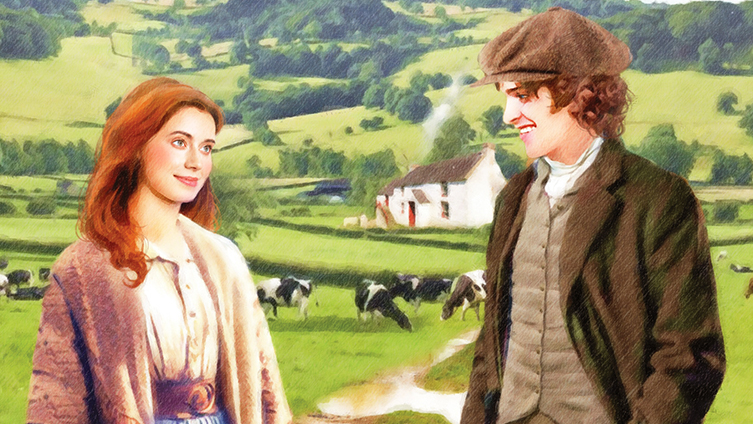

Her English Summer

To Niamh’s mother, George was the enemy. Could she persuade her otherwise?

Illustration credit: Ruth Blair

Subscribe to The People’s Friend! Click here

To Niamh’s mother, George was the enemy. Could she persuade her otherwise?

Illustration credit: Ruth Blair

A ROMANTIC SHORT STORY BY WENDY JANES

To Niamh’s mother, George was the enemy. Could she persuade her otherwise?

The early morning rays of summer sunshine warmed Niamh’s face.

She returned along the two-mile dirt path leading from the O’Brien cottage back to her family’s large dairy farm.

Hoisting up her long skirts, she stepped to one side to avoid a large, muddy puddle from last night’s rain.

She loosened the shawl that had kept her warm on her walk to the cottage and glanced down at the empty basket hooked over her arm.

Earlier, it had contained a loaf of bread she’d made and a dozen eggs laid by the hens she tended daily.

On her parents’ instruction, she’d got up an hour before dawn to make the delivery.

Not wanting to embarrass or disturb Mrs O’Brien, Niamh had left the items wrapped in a muslin cloth on her doorstep.

Her parents always said it was their Christian duty to help those less well off than themselves, and Mrs O’Brien was in sore trouble.

The O’Briens’ only son had emigrated to America right after the Irish Free State had been established six years ago, leaving the two of them to work the patch of land they rented along with the cottage.

That had been hard enough, but then Mr O’Brien had been taken bad with the influenza on Palm Sunday, and had passed away on Easter Sunday.

Niamh paused as she caught sight of the slate roof of her family home in the far distance, the chimney sending up puffs of smoke.

She gazed across the fields to the parlour where her da and her two older brothers, Colm and Finn, were milking the herd.

Further to the west were the stables where her younger brother, Darragh, would be grooming the horses, one of which he’d hook up to the cart in order to take her to this afternoon’s mid-week market.

Although he was the youngest child, he was the bravest, wildest and most wilful of them all.

He’d even been known to disagree with Mammy on occasion, which was a terrible thing to witness.

He’d been hopeless with the cows, but thank goodness he’d found a stillness when he was with the horses.

She resumed her journey home and was halfway there when she saw a tall male figure coming along the path towards her.

Unable to recognise his outline, she wondered what a stranger was doing out here.

She saw he had a mass of brown curls that seemed to be trying to escape from under a felt cap, and he was wearing a thick jacket over a collarless shirt.

One hand was thrust into his trousers pocket and the other was carrying a small suitcase.

As he got closer she realised that the young man was smiling directly at her.

She looked down at the tips of her boots poking out from beneath her skirts.

“Good day,” the man said.

The surprise at hearing English made her glance up.

She gasped when the bluest eyes she’d ever seen twinkled back at her.

“It’s a beautiful morning, isn’t it?” the stranger asked in his lovely voice.

Niamh had learned both English and Gaeilge at school. While she loved her own language, there was something about the English language that spoke of daring and adventure.

Things she’d never experienced in all her seventeen years.

Niamh gave a quick nod and hurried on, eyes firmly back on her boots.

There was only the O’Brien cottage at the end of the path, but what would an Englishman be doing visiting Mrs O’Brien?

She’d ask later at breakfast if anyone in the family had heard anything.

Soon everyone was settled at the table, drinking mugs of tea and tucking in to porridge, hunks of bread and butter, and thick rashers of bacon.

As usual, her da was complaining about the rates the Co-operative were paying for the herd’s milk, which was turned into cheese and butter at the creamery.

Niamh waited until her da had run out of steam.

“I saw a gentleman heading towards the O’Brien cottage this morning –”

“The rumours are true, then,” Mammy snapped before she had a chance to say any more.

Mammy continued as though they’d not uttered a word.

“There’ll be no more hand-outs from us now.”

“Why be so harsh, Brigid?” her da asked. “What was the poor woman to do?”

“She should have asked for help from kin closer to home.

“Or insisted her no-good wastrel of a son come home to do his duty by his family.

“She’s always been too soft. And look where it’s got her.”

“Come, now, she’s a good woman fallen upon hard times.”

Mammy pursed her lips and made a face that her husband and four children recognised as her declaration of “disagree with me at your peril”.

Niamh had been trying to follow the conversation, but she was too nervous of upsetting Mammy further to ask what rumours she was talking about.

She hoped one of her brothers would speak up.

Sure enough, bold as brass, Darragh asked.

“What has Mrs O’Brien gone and done?”

“The woman’s only brought over her cousin’s lad.”

Here she paused and took a deep breath.

“From England,” she spat out.

Mammy’s dislike of the English was legendary.

Niamh was too young to clearly remember a time before the Irish Free State, but she knew it was a political thing, and it was the reason why lots of people in the area said negative things about the English.

However, Mammy’s attitude seemed more of a personal thing, which Niamh didn’t dare to ask about for fear of her sharp tongue.

Niamh knew better than to let slip that the young man over from England had smiled at her less than an hour ago, and he’d spoken to her, too.

In fact, Niamh thought the good Lord himself would probably be more understanding about what happened than her mother, who was telling them all to keep their distance.

All through the morning, Niamh kept seeing those beautiful blue eyes and hearing that delightful voice.

They accompanied her as she loaded the cart and for the hour it took Darragh to take them to the nearest town for the weekly market.

Darragh unhitched the cart in the usual spot and rode off to find his friends for a game of football.

As people came up to buy the eggs and other produce from the back of the cart, she enjoyed hearing about the various engagements, births, health issues and squabbles that filled their lives.

She was thirsty for their news since nothing of interest ever happened in her own life.

On occasion her brothers would attend a local dance or a football match, but she wasn’t allowed to go.

She had learned to silence the little voice that questioned why her brothers had more freedom than she did, and she was grateful her parents allowed her to sell their wares at the market, as long as Darragh accompanied her.

Niamh was just casting her eyes over the few unsold items when she looked up and saw those twinkling blue eyes.

She instinctively took a step back, glancing from side to side, hoping no-one would report to Mammy that she’d been seen talking to Mrs O’Brien’s relation from England.

Gossip could spread like wildfire in the county.

“Hello, again.” He raised his cap. “It is you, isn’t it? From this morning?”

She nodded and couldn’t stop a little smile playing on her lips.

Nor could she stop looking into those blue eyes.

“My name is George Wilson. I’ve come to help Mrs O’Brien.”

He paused, obviously waiting for her to respond with her name.

“I’m Niamh Tierney.”

She noticed that now he was no longer wearing his thick jacket, his white shirt was the whitest white she’d ever seen.

“Oh, from the Tierneys’ farm?”

She nodded again.

“You’re so lucky,” he said.

She frowned, not understanding how she could possibly be lucky.

“You live in such a beautiful, lush, green land.” He ran his hand through his curly, springy hair. “I’ve seen so many beautiful sights in the short time I’ve been here.”

She sensed he wasn’t just talking about the countryside and felt a fiery blush flood her cheeks.

Niamh’s heart thumped in her chest, but this was altogether different from when she got out of breath wringing the family’s clothes on wash day.

She needed him to go away.

She longed for him to stay.

George was clearly oblivious to her turmoil.

“I hope I’m not being too forward, but I don’t know anyone in the area. I was wondering if you would show me around?”

“I’m sorry. I’m not allowed…”

This time it was George who looked confused.

At that moment, Darragh returned, red-cheeked and sweaty from his football game.

He swung down off the horse and greeted George.

When he discovered who he was, he immediately offered him a lift home on the cart.

“But what about Mammy?” Niamh hissed.

“Oh, Mammy’s bark’s worse than her bite.”

Darragh laughed as he hitched the horse back on to the cart.

“If she finds out, don’t worry. I’ll take the blame.”

And then Darragh told George far too much about their mammy’s temper and her dislike of the English.

“Under the circumstances, I shall decline your generous offer of a lift,” George replied.

He turned to Niamh.

“I wouldn’t want you or your brother to get into trouble on account of me, Niamh.”

The way he said her name in his English accent made her heart melt.

“It’s been lovely to meet you both, and I hope, in time, your family will see I’m a decent Englishman. Until then…”

He lifted his cap and gave a bow.

Niamh watched him stride off.

Over the next few days, thoughts of George filled Niamh’s mind.

At church on Sunday, she couldn’t stop picturing his handsome face.

After Mass, she followed her parents and her brothers down the aisle of the church and saw George helping Mrs O’Brien to her feet.

He seemed to turn instinctively at her approach and smiled.

Safely behind her family, she smiled at him from beneath her hat, her heart thumping for fear of the thunderbolts about to strike her for her wantonness.

The following week at the market, Darragh was in the middle of explaining he’d stay with her, rather than go off for a game of football with his friends, when she saw George making his

way towards them.

Darragh gave her a wink, and she realised he must have somehow spoken with George and arranged to be there so there could be no suggestion of impropriety.

Darragh and George chatted about horses and football while Niamh served any customers.

Then, while Darragh served, she told George about her family and George told Niamh about his.

Like her, he had three brothers and four uncles.

Throughout the rest of the summer, which always coincided with the times Darragh wasn’t playing football with his pals, George would happen to pass by at the market and spend a few precious minutes speaking with them.

Bit by bit, she learned about his life in England: how proud his father was of his Irish roots.

How George hated living in the town, and longed for the countryside, but the closest he’d come was working for a brewery who used huge horses to cart the beer around to pubs.

When the call for help had come from Mrs O’Brien, he’d jumped at the chance.

Niamh loved how he’d usually address Darragh in Gaeilge, but he’d speak English with her.

The more time that passed, the more fond she grew of George, and the less worried she became that anyone would tell Mammy about their meetings.

Niamh’s eighteenth birthday fell on the third day of September, a Monday.

At breakfast, Darragh said he’d take her for a special ride on the cart for fun, and suggested she could dress up in her Sunday finest.

Mammy agreed to let her off her chores, seeing as it was a special day.

Niamh skipped down to the stables, and was surprised when neither the cart nor Darragh were waiting for her.

She stepped inside the stables and called Darragh’s name.

George stepped out from the shadows.

“Happy birthday,” he said.

“Oh.” Niamh put her hand to her chest in surprise.

“I hope you’re not disappointed that I’m your present rather than the cart ride.”

He grinned at her.

“Not at all.” She grinned back.

“When Darragh told me it was your birthday today, I had to see you.”

His smile wavered, and he tentatively reached out and took her hand in his.

“Niamh, I love you.” He stopped, his blue eyes so earnest. “Please, tell me you feel the same.”

“I do, George,” she whispered. “I love you, too.”

He brought her hand to his lips and kissed it gently.

He leaned forward, then paused, an unsaid question in his eyes.

She inclined her head and he kissed her on the cheek.

Suddenly there was a cry from the doorway and Niamh’s mother came hurtling towards the two of them, shoving George backwards and grabbing hold of Niamh’s arm with her bony fingers.

“When I heard the filthy gossip about you and this creature, I didn’t believe it.

“I swore that no daughter of mine would lower herself to speak to an Englishman.

“But when Darragh came up with that nonsense about the cart, and then I didn’t see hide nor hair of it, I knew.”

At that moment, Darragh rushed in, looking aghast at the sight before him.

Before he could say a word, Mammy cried, “Here’s my other deceitful child.”

“But, Ma –”

“Don’t you dare interrupt me. I’ll deal with you later.”

She turned to Niamh.

“You have brought ruin to this family, just like my sister did.”

“Sister?” Darragh and Niamh said together.

Niamh was stunned; she only had uncles.

“Oh, yes, I had a little sister. Róisín was the same age as you when she left with that Englishman.

“It’s not going to happen again.”

With that, she hauled Niamh from the stables and into the courtyard.

Niamh cried out in shock.

George and Darragh ran out after them.

“Mam, you’re hurting her,” Darragh cried.

“Please, Mrs Tierney,” George said.

Mammy ignored them and dragged her all the way back to the house, up the stairs and into her bedroom, locking the door behind her.

Niamh threw herself on to her bed and sobbed.

Eventually she calmed sufficiently to hear what was going on downstairs.

She heard the awful sounds of Mammy and Da shouting, her older brothers’ voices joining in the fray.

It was the middle of the afternoon and everyone was indoors.

No-one was working and everyone was angry.

And it was all her fault.

The urge to climb out the window and run away was strong.

Could she run to George? Where might they go?

She was startled from her thoughts by a loud knock at the front door.

There was a moment’s silence, then more raised voices. Mammy’s was the loudest of all.

Next she heard George’s voice, low and humble, followed by the front door slamming shut.

Then more arguing, and what sounded like her brothers leaving the house, probably to return to work.

Afterwards came her da’s footsteps on the stairs.

He unlocked her door and, with an apologetic expression, he beckoned her to come downstairs.

She trailed him into the kitchen where Mammy sat with her head in her hands.

Da kissed the top of Mammy’s head, sat beside her and put his arm around her shoulders.

Mammy raised her head, patted his hand and gave him a weak smile.

Such a show of intimacy between her parents was rare.

Her da looked so tired, but her ma looked worse; around her ashen face lay strands of greying hair that had escaped from her normally neat bun.

Despite what had just happened, Niamh’s heart went out to her ma, and to her long-lost aunt.

Her da began to speak.

“You should never have gone behind our back, Niamh.

“You, Darragh and that young man have disrespected this house.”

“I’m sorry, Da. Ma. It was wrong of me. I know that.

“But I swear, we have only spoken, and Darragh has always chaperoned us.

“I love George,” she stated.

“Love,” her ma spat. “You know nothing.”

“And he loves me,” Niamh continued. “He’s a good man.”

Her ma raised her eyes to heaven.

Her da replied.

“Yes, so we are beginning to understand.”

He glanced at Mammy, who pursed her lips.

“You may have heard from upstairs. George came to the door and, in Gaeilge, he humbly apologised for the deception you played on us.

“He also assured us that no impropriety took place between the two of you.”

Mammy tutted and cleared her throat.

“We can overlook a kiss on the cheek, can’t we, Brigid? We were young once,” Da said.

“But we weren’t strangers. We’d been to school together. Our parents were friends. We went to the same church.

“We had everything in common. Whereas we know nothing about that man. We can’t trust him.”

“Why not?” Da asked. “He stood on our doorstep and bared his heart to us. That takes guts.”

“It takes brazen cheek,” Ma replied. “Typical of the English. Untrustworthy, the lot of them.”

Niamh couldn’t help herself.

“But surely there’s good and bad wherever anyone comes from? George is good, brave and kind.”

“You sound exactly like my sister,” Ma said. “She’d lie in our bed at night telling me about her wonderful Englishman.

“Even persuaded Da to let them marry on the understanding they’d stay here, and he’d work on the family farm.

“Then within the year her husband had filled her head with stories about England, and when Da said no, they ran off.

“Upped and went without a word. I thought she might send a letter, but no.

“We never heard from her again.” Ma sobbed. “I still miss her.”

Da reached out to hold Ma’s hand, but she refused to take it.

Instead, she stood.

“And that’s why you’re not to see that man again. He’ll steal you away.”

“But Ma,” Niamh said gently. “I’m not your sister.

“George wants to stay here. He doesn’t even like England.”

Her ma looked at her through tear-filled eyes.

“Ah, Brigid, listen to the girl.” Da got to his feet, too. “I, for one, am impressed by the lad.

“I think we should allow them to step out together.”

“Let me think about it,” Ma replied. “Meantime, you’re not to leave the farm till I’ve made up my mind.

“And woe betide you if the two of you set eyes on each other before I’ve given my permission.”

She marched to the sink.

Niamh and her father exchanged a smile.

The week crawled by for Niamh.

She tried her very best to do all her chores perfectly.

She didn’t dare mention George’s name, but he was in her mind and in her heart the whole time.

Having been told about the situation, Colm and Finn had gone round to the O’Brien cottage to warn George not to even attempt to get in touch with Niamh, but to wait word of the outcome everyone was now hoping Ma would agree to.

Her brothers and her da had been telling Niamh how they’d been ever so carefully trying to encourage Ma to make the right decision.

On Sunday morning, Niamh was lying in bed wondering whether or not she’d be allowed to go to Sunday Mass.

She was about to get up when her ma came into her room.

“You’re to get ready to come to church with us today,” she said, then left the room.

Niamh’s heart leapt. Did this mean her ma had made a decision?

Would it be the one she’d been longing for?

George always accompanied Mrs O’Brien to church.

Maybe her ma had got word to him that he mustn’t attend church, which surely was too much even for her.

Or maybe her ma knew he’d be there, which meant she’d decided to allow them to at least set eyes on each other.

And if that were the case, maybe they’d be allowed to speak, or maybe even spend time together.

Niamh sat in their usual pew, unable to turn around to see if George and Mrs O’Brien had arrived and were sitting their usual places a few rows behind the Tierney family.

Darragh, sitting next to Niamh, nudged her moments before the Mass began.

“He’s here,” he whispered.

Niamh’s eyes filled with tears. The hope was overwhelming.

At the end of Mass, which seemed go on for even longer than usual, they were filing out into the churchyard when Niamh saw George and Mrs O’Brien.

They looked across the churchyard at each other, and it took all of Niamh’s willpower to stop herself from running over to him.

Next moment, Ma took hold of Niamh’s arm and led her over to George and Mrs O’Brien.

“I have made my decision,” Ma said without greetings or any to-do. “Mr Wilson may visit Niamh at our home once a week under my supervision.

“Darragh will resume accompanying Niamh to market as chaperone.

“What happens after that will be in the good Lord’s hands.”

“Thank you, Mrs Tierney,” George replied in Gaeilge.

George and Niamh took one step towards each other, then stopped.

They both glanced at Mammy, who gave a tiny nod of assent.

And as Niamh stepped into George’s arms, she knew they had been given the highest blessing.

Enjoy exclusive short stories every week inside the pages of “The People’s Friend”. On sale every Wednesday.

Alison Carter

Teresa Ashby

Beth Watson

Alyson Hilbourne

Katie Ashmore

Kate Hogan

Liz Filleul

Beth Watson

Alison Carter

Sharon Haston

Kate Finnemore