With Room To Grow

All Seònaid wished for was for some hope to blossom in her granddaughter’s heart...

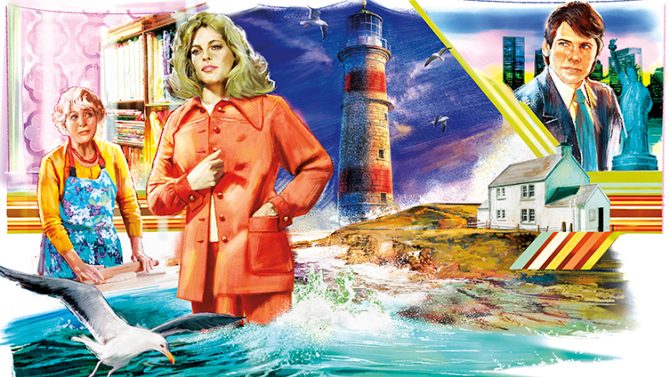

Illustration credit: Mandy Dixon

Subscribe to The People’s Friend! Click here

All Seònaid wished for was for some hope to blossom in her granddaughter’s heart...

Illustration credit: Mandy Dixon

MODERN LIFE SHORT STORY BY ALISON CARTER

All Seònaid wished for was for some hope to blossom in her granddaughter’s heart…

The cold pressed on Seònaid, crushing her ears where they peeped out from the lower edge of her beanie hat.

Why did she ever think of Christmas as a wintry time?

Winter was now, late January and the first days of February, when her knees creaked with the cold if she walked her hillside more than half an hour.

She should have put her walking boots on instead of wellies.

But she had no expectation of being out long. Not with Ishbel, who had made it clear that she didn’t like nature.

“We might see snowdrops,” Seònaid said.

The girl trudged, head down.

Her ankles were bare. Seònaid shook her head.

But she told herself that her granddaughter’s inadequate clothing was not going to kill her.

No response came to the mention of snowdrops, and they walked on.

It was a start – Ishbel even agreeing to a walk.

She’d been at the house four days with barely a movement except a finger on her phone, and eating.

The child was eating, which was a blessing.

“I’d forgotten,” Seònaid began, “until I saw the calendar this morning, that they have other names.

“One is ‘Fair Maids of February’.”

“What has names?” the child said.

Ishbel wasn’t so much a child now, at fourteen.

“The snowdrop.”

“I read that it’s also called ‘Little Sister of the Snows’,” Seònaid added.

“Cute,” Ishbel said.

Seònaid knew she was starting to repeat herself, and teenagers got bored so quickly.

But what else was there to talk about?

Ishbel refused to talk about her parents.

Seònaid’s daughter and her husband were getting divorced.

The concept was fresh to both these winter walkers. The news was less than a month old.

Both were shocked.

Seònaid had offered to give her granddaughter a short holiday.

Seònaid’s daughter Anna, Ishbel’s mother, said the school thought the absence was worthwhile to help the girl’s mental health.

Seònaid had been to Ishbel’s Edinburgh school.

It was all concrete, and it was crying out for someone to plant some trees there.

Seònaid’s own mental health wouldn’t fare well there, but she had lived most of her life in the middle of nowhere, so what did she know?

It was hard to cheer a girl up when it wasn’t above six degrees all day.

“It’s a thing I’ve always liked about the snowdrop,” Seònaid said, mentally kicking herself for going on about the flower.

“It flowers when winter is at its bleakest.

“I see it as a symbol.”

Ishbel blew out her breath into a great cloud.

“Symbol?” she said, a little scornfully.

Seònaid ploughed on.

She’d been given the thankless, uphill job of trying to cheer the girl up, or at least mind her as she raged.

Ishbel had done no visible raging. It was all inside her mind.

The girl had other problems that crowded in on her, too; like the bad results in her school tests and the braces on her teeth which never stopped aching and losing their tiny elastic bands.

“I’ll tell you a story about the snowdrop,” Seònaid said. “A legend, if you will.”

Ishbel sniffed.

Yet silence did not feel like a good option to Seònaid.

It encouraged misery in this particular child.

She looked at Ishbel’s long dark hair.

“It will all be all right,” she wanted to tell her.

“You are beautiful, and you are bright despite those tests.

“I love you. Your mum loves you, and so do your father and your brothers, and you have a great future before you.”

But the girl wouldn’t listen.

Seònaid knew the young enough to know that much.

“The snowdrop is a symbol,” she said, “or if you don’t like symbols, it’s a sign of hope.

“Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden, and it was a terrible time for them.”

“Granny,” Ishbel said heavily.

Ishbel had arrived on a Saturday and her first comment had been that no way was she going to church in the morning.

“This is just Adam and Eve, and just a legend. Surely you can tolerate that?” Seònaid said.

“OK,” Ishbel said. “Will we turn back soon?”

“Let’s go through the copse, then back.”

“OK.” Ishbel sighed.

“Well,” Seònaid began again, “there’s Eve – miserable, regretful, about to give up hope.

“What a terrible thing, to be close to giving up hope.”

The girl’s head dropped again, her arms clamped to her sides.

“Eve wondered if the long winter would ever end,” Seònaid went on.

“Then, out of the blue, an angel appeared.”

“You said it was just Adam and Eve,” Ishbel pointed out. “What’s with the angel?

“Also, I’m hungry. Have you got anything to eat?”

“Sorry, sweetheart, I don’t. But it’s not long to home.

“Anyway, let me have the angel.”

She saw the hint of a smile on Ishbel’s face, but quickly it vanished.

“The angel stood there, looking at Eve, just as snow began to fall.”

“It had better not snow now. Will it snow? My head will freeze.”

Seònaid had offered her other beanie hat to Ishbel, but it was refused.

Nobody, apparently, wore them any more, and Ishbel would not be seen in a red beanie for any money.

If they were to get snowed in, the house was half a mile from the nearest other human being.

Seònaid didn’t mention that, either.

Her granddaughter was, for now, to be given the kid glove treatment.

“Let’s hope the snow holds off here, sweetheart,” Seònaid said.

Seònaid smiled.

“Back to the legend. The snow began to fall, and the angel reached out and caught a few flakes, and turned some into the flowers that we now call snowdrops.

“The angel breathed life into them. They come back every snowy time of year. And that is proof that winters turn into springs.”

“Proof? How is that proof?”

“Well, the flower comes back every year.”

Seònaid hoped Ishbel was not going to start an intellectual argument.

But Ishbel left it at that.

They walked on.

The copse loomed ahead, the trees close together, their branches bare and twisted.

Seònaid loved it here, but Ishbel was unlikely to.

“What’s the date?” Seònaid said.

She knew, but she needed conversation topics.

At least the sky was getting lighter.

If she was lucky, a milky sun might show itself before the end of the walk.

But it was so, so cold!

Seònaid allowed herself a brief daydream about her walking socks, tucked into the back of her drawer.

“I can’t remember my own name these days,” she said. “What’s the date?”

“I don’t know, Granny.”

The tone made Seònaid smile – the girl considered her beyond dim-witted.

“If it’s Friday, it must be February the second,” Seònaid said. “My goodness, it’s Candlemas.”

She remembered something from a book she’d had as a girl.

It had been full of lovely illustrations.

“The snowdrop, in purest white array, first rears her head on Candlemas Day,” she said.

Ishbel stopped suddenly, her feet making the frost crackle underfoot.

“That rhymes, but doesn’t scan. There are too many syllables in the second line.”

“True,” Seònaid conceded. “Anyway, Candlemas is the celebration of Jesus being presented in the temple.

“It’s one of the oldest festivals.”

“Granny,” Ishbel said, in a warning voice.

“Sorry,” the elder woman apologised. “Ah, we have reached the copse.

“We’ll duck our heads in and see what’s what, then head back for some of that cake, and cocoa.”

“People don’t drink cocoa any more, Granny,” Ishbel said. “They drink hot chocolate.”

“We’ll have that, then.”

The girl’s voice was still flat and dull.

It seemed to Seònaid that Ishbel was holding on to her unhappiness, clinging to it because she felt it was all she had.

Seònaid allowed herself a moment of worry.

These days some young people seemed to drown in their troubles.

They lacked resilience.

Or maybe, she thought, it was just that in my day, they drowned but we didn’t see them doing it.

The ground of the copse was easy underfoot, all needles and moss, and very dark in colour.

Seònaid looked up as some of the weak sunshine she had been hoping for broke through.

“Ever seen a winter aconite?” she said.

Ishbel rolled her eyes.

She would go home to her mum, Seònaid knew, with tales of Granny – how all she knew about were plants and church stuff.

“No,” the girl said.

“Oh, lovely little yellow things,” Seònaid went on.

“I have some in the garden, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen them on this walk.

“They share something with the snowdrop.”

Ishbel stopped again.

“Is there really more to say about snowdrops?”

Seònaid laughed, but Ishbel’s face was stony.

“The winter aconite flowers about this time of year, to take advantage of any sunlight it can get.”

Seònaid looked up.

“Before the light is blocked by the tree canopy. See.”

But Ishbel continued to gaze at the ground.

“Winter has its benefits,” Seònaid said.

“The trees can be bare and everything can be bad, but a few flowers get the best out of it.”

Ishbel turned to her.

“It’s obvious what you’re doing, Granny. The whole metaphor thing won’t work on me.”

The child was so sophisticated, so cynical!

Seònaid sighed.

Ishbel set off into the denser trees.

Seònaid had not been here for a while.

She wondered if a tree that had died in the summer would have fallen over by now.

Then the child changed course, making her way round the one huge beech in the copse.

“Oh!” Ishbel’s voice was different.

Seònaid took two steps to get round the tree.

There, spread like an eiderdown of bright perfect white, were hundreds – maybe thousands – of snowdrops.

The whiteness stretched out under the trees, more solid with distance.

“It’s beautiful,” Ishbel said.

“I can’t believe… I had no idea.”

Seònaid thought of the city Ishbel lived in, where she was born and raised.

It might be years since she had been such a sight.

Perhaps she never had.

Ishbel stood for a long time, drinking in the sight.

She got out her phone and took photos.

Seònaid could almost reach out and touch Ishbel’s mood as it lightened.

The child pushed back her long hair.

“It’s an OK walk,” she said.

Seònaid blessed the snowdrop, the bell of Candlemas, and they set off back home.

Enjoy exclusive short stories every week inside the pages of “The People’s Friend”. On sale every Wednesday.

Deborah Siepmann

Alison Carter

Teresa Ashby

Beth Watson

Alyson Hilbourne

Katie Ashmore

Kate Hogan

Liz Filleul

Beth Watson

Alison Carter