There’s Always Tomorrow – Episode 10

There's Always Tomorrow by Mark Neilson

« Previous Post- 7. There’s Always Tomorrow – Episode 07

- 8. There’s Always Tomorrow – Episode 08

- 9. There’s Always Tomorrow – Episode 09

- 10. There’s Always Tomorrow – Episode 10

- 11. There’s Always Tomorrow – Episode 11

- 12. There’s Always Tomorrow – Episode 12

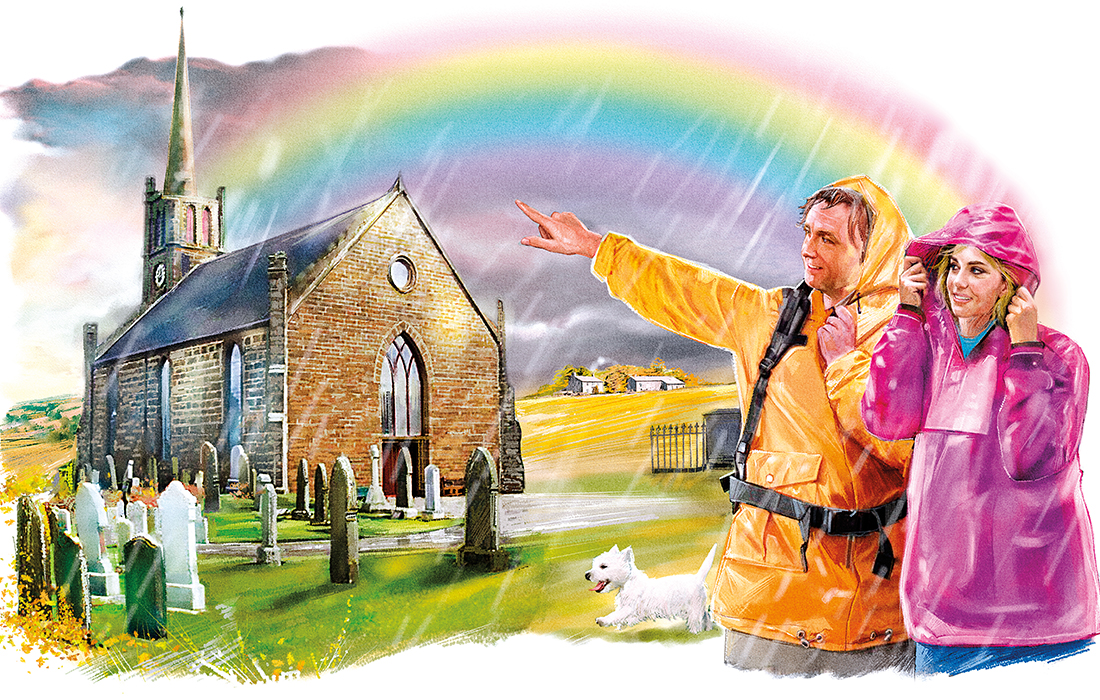

The sudden shower swept across from the hills, sending the temperature plummeting while the rain came down in sheets.

“Inside, Wullie!” Lorna shouted, running to the kitchen door.

He straightened up, water dripping from his cap.

“Why?” he asked. “It’s only rain. It stops at the skin.”

“I’m making a cup of tea,” she called from the kitchen.

“That’s different. I’m on my way,” he returned, bringing in his fork and the rake she had been using.

He parked these in the deep shelter of the doorway, then looked as if he was about to do the same with himself.

“Don’t stand there,” Lorna demanded. “You’re letting in a draught.”

He shuffled inside, closed the door and stood with his back to it, dripping water on to the door mat. He looked lost and uncertain.

He was shy, Lorna realised, behind the gruff exterior.

“Hang your wet stuff on the pegs behind the door,” she said more gently.

He shrugged out of his old tweed jacket, a bit like a crab discarding its carapace, looking vulnerable and lost.

“Sit here at the kitchen table,” she said.

“Right.”

Out of the corner of her eye, Lorna saw him look down at his feet, then stoop to untie the laces and take off his boots.

He was wearing thick woollen socks sensible for any outdoor man, but his toes were poking through both of them.

She smiled.

“If my dad’s hand shears were a disgrace, Wullie, what about these socks?”

He smiled wryly, tucking his feet under the table and out of her view.

“They’re only working socks,” he replied. “They look decent enough when my boots are on.”

She poured milk into both mugs.

“Sugar?” she asked.

“Yes, please.”

“Sugar’s bad for you,” she warned. “How much?”

“Two spoonfuls. Heaped.” Wullie’s eyes stared up at her defiantly.

Sighing, she put in two flat teaspoons – as much as her conscience would allow – and stirred the tea.

Lorna handed his over, then sat down at the other side of the table.

“We’ve got that flower-bed nearly finished,” she said. “But the soil is more red than brown.

“Is there iron or something in the ground, discolouring it? Should I order new soil at a garden centre?”

Wullie raised a bushy grey eyebrow.

“Then ye had better order enough fresh soil for the whole of the Mearns,” he declared. “Have you never heard of the red soil of Kinraddie?”

Lorna frowned.

“That’s Lewis Grassic Gibbon, isn’t it? His novel ‘Sunset Song’.”

“Aye. For a man of books, he got his farming right.”

“Don’t tell me that you’ve read it!” she exclaimed.

“Aye, and without moving my lips, either.” A faint grin appeared on his weather-beaten face.

“You’re a man of hidden talents, Wullie.” She smiled.

“Maybe, but they’re few and buried deep.”

“Of course, this is the Mearns of ‘Sunset Song’.” Her mind ranged back. “It was such a bleak landscape he described. And farming such a thankless task.”

“Crofting,” Wullie corrected her. “It barely scratched a living. You need the scale of modern farms, with mechanisation, soil analysis and balanced feeding.

“But it was a good story. His characters were real people. You’ll still find folk exactly like them in any village round here.”

Helen nodded. The story had made a huge impact on her as a student. She had loved the rhythm of the words.

It read more like poetry, at times, than prose. And, as Wullie said, its main and fringe characters were solid and authentic.

The thought triggered another question in her mind.

“What happened to the village shop? Why did it close down?”

He sipped his tea.

“When Jimmy Scobie lost his wife, he couldnae be bothered to run the shop. And the village is dying on its feet these days.

“All the younger men went off to work on the oil rigs, then took their families away, leaving the older folk behind.

“Jimmy’s shop barely made a living, but it helped people here.

“With his wife gone, he didn’t want to carry on,” Wullie explained. “He went to stay with his daughter. The shop’s been empty ever since.”

Lorna frowned.

“So where do people get their shopping?”

Wullie shrugged.

“They drive to Inverbervie. If they’ve no car, they can order online. Get their weekly shopping delivered.”

“But the small things. The bits and pieces you forget to buy or order?”

Another shrug.

“You do without.”

Lorna rose, gathering the mugs and taking them over to the sink.

“Why doesn’t somebody do something about it?” she asked. “Re-open the shop?”

“Because it doesn’t sell enough to make a profit,” he replied.

“What if it doesn’t want to make a profit, but only cover its costs? To provide a local service?”

He stared at her.

“No profit? Any mannie who did that would be off his head,” he declared. “The rain’s stopped. Your garden will never get done by sitting here.”

He rose.

“Now don’t you be staring at my toes. It embarrasses me.”

“I’ll buy you another pair of socks at Christmas.” She smiled.

Then her smile faded.

“Wullie, does it have to be a mannie who opens up the shop? What if it’s . . .” She searched for the word. “What if it’s a wifie?”

The grey eyebrows came down.

“Ach,” he said. “That’s different.”

“Why?”

“Because women will do what they want to do whether it makes sense or not.

“The more you try to talk reason to them, the more determined they become.”

He sighed, staring at her.

“Now don’t you be getting daft ideas,” he warned. “It’ll end in tears.”