The Tanner’s Daughter – Episode 29

The Tanner's Daughter by Pamela Kavanagh

« Previous Post- 1. The Tanner’s Daughter – Episode 01

- 1. The Tanner’s Daughter – Episode 29

“Mistress Leche?”

Dorcas’s tone was more querulous than was acceptable in a servant and Jane turned to her sharply.

“Yes, girl. Do what you must and be quick about it. Dear goodness, is that the hour striking? I should be at my desk by now.

“Mind you close the casement when you are done here, Dorcas. The draught makes the fire smoke.”

A final jerk to the offending headdress, and Jane vacated the room.

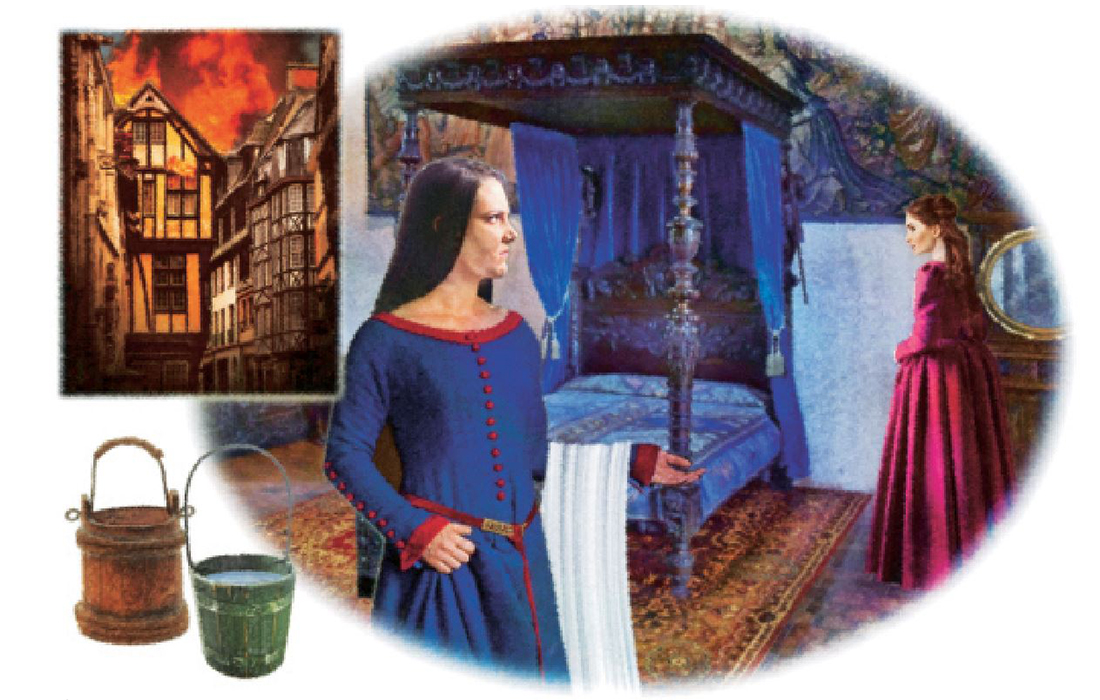

Tight-lipped, Dorcas put away the linen and then slammed shut the open casement, provoking a protesting huff of smoke from the chimney.

She looked around her. A pox on Will Leche! All her enquiries as to his origins had come to nothing.

The very nature of it all seemed suspect. He was too careful, too intent on covering his tracks. Why?

All she needed was a single clue.

Dorcas scanned the room again. In here, the furniture mostly contained Mistress Leche’s garments, apart from a heavy oak writing-desk under the window where the young mistress attended to her personal correspondence.

What if the husband did likewise?

Blessing her mother’s wit for ensuring that her daughter knew her letters, a fact she had not disclosed to the mistress, Dorcas went to riffle through the drawers and cupboards of the desk.

Nothing. Nothing but bundles of dressmaker’s bills and such. Nothing at all relating to him.

Dorcas decided to try his dressing-room. She was taking a chance, since Master Will was known to slip back to check his appearance in the looking glass before venturing out on business or to his gloving shop on White Friars.

Dorcas darted into the adjoining room, wrinkling her nose at the pungent smell of hair pomade that met her.

She headed straight for the carved oak coffer that held his belongings.

It was full to the brim and she had to remove some of the clothes, piling them carelessly on the planked floor.

Right at the bottom was a saddlebag.

Listening out for a step in the corridor beyond, Dorcas began to search the various compartments, her fingers struggling with the stiff leather straps and buckles.

And there, tucked into a pocket where it must have been overlooked, was a scrap of parchment with writing in faded ink.

Eyes gleaming in triumph, Dorcas stowed it away in her bodice, before replacing everything back in the coffer.

Shortly afterwards she was out of the room and descending the staircase, a dusting cloth in hand; a housemaid going about her daily duties.

In the office, a sealed letter awaited Jane.

“It came off one of the Irish boats,” Will said. “A lad brought it by request of the harbourmaster.”

“Jethro Taggart? What can this be?”

Jane broke the seal and unfolded the parchment, scanning her eye over the content.

“It is from Diarmaid O’Hare, the Drogheda merchant that Father dealt with.”

“The man whose ship was lost in a storm and a vital order with it? What does he want?”

“He has obtained another ship. He wishes to know if we would consider resuming trading with him.”

Jane looked up.

“His skins were of the best quality, Will, and very reasonably priced. Father had every faith in him.”

“Oh, yes? Is that all he says?”

“No. He had heard about Father. He sends his condolences and says how much he valued dealing with Father.

“A fair and excellent man to do business with, he says.

“Here, you read it.”

She passed the letter to Will and occupied herself with opening more correspondence while he perused it.

“What do you think?”

“About resuming trading? Well, I am in agreement but for one thing – this silting of the estuary.

“I was talking to a horse dealer from Ireland only recently. He said the channel to the harbour had narrowed drastically over the past year.

“How long will it be before Chester ceases to be a port altogether?”

“That is a risk all traders take.”

“But not us, Jane. Where is the next port from here?”

“A three-hour ride northward along the coast. A place called Little Neston, very small and poor.”

“No matter, as long as it serves our purpose. Want me to look into it?”

“It would do no harm.”

“Then I shall put it about what our intentions are and suggest that other merchants do the same.”

Will paused, thoughtful.

“When is the next guild meeting?”

“Friday week. Why so?”

“You might inform them as well, but with reservations.

“We do not want to antagonise them any more than we need and they could take umbrage to our taking the trade – and the revenue it brings – away from the city.

“What if we play them at their own game? What if you suggest they put it to the City Authorities that they draw up a plan for building a workable port at – where was it?”

“Little Neston.”

“Aye. Do not let them know that the idea stemmed from me, or it stands to be rejected on principle!

“Let them think the idea arose from your late father. He and I discussed the silting threat often enough.

“I might also have a word with our vintner and grain merchant acquaintances – decent fellows, both.

“Likely they will think fit to put the idea to their own guilds. There is strength in numbers, Jane.

“If all the subsidiaries were to join forces and put it to the Town Authorities, there is a chance that between them they could persuade the privy council to raise some cash to fund the building of the new port, thereby retaining the customary revenues.”

“You think so?”

“Well, I would not know for sure. How Chester’s governing bodies work is a mystery to me and seems likely to remain so. All I can say is we can but try.

“And Jane, when you attend the guild meeting make sure you dress for the part.

“Wear your crimson farthingale and embroidered kirtle. Your finest ruff, and chopines on your feet to give you height.”

Jane pulled a face.

“The deep soles make me feel I am walking on stilts.”

“It will give you dignity. And wear your jewels. That will impress the most cynical of them.”

Jane raised an eyebrow.

“Anything else, husband?”

“Not for the moment,” Will said, grinning.

Jane turned her attention back to the letter.

“Do I write and inform Mr O’Hare that we shall be pleased to resume trading with him?”

“Aye, do that. And if the Guild does not rise to the occasion, be it on their own heads if revenue is lost because they have failed to listen to reason!”