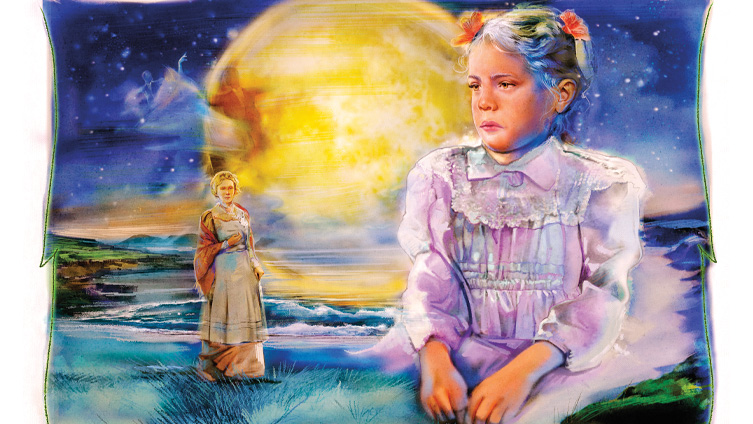

The Moon Child

On the rugged shoreline of this forgotten isle, Catriona had met her kindred spirit...

Illustration: Sailesh Thakrar.

Subscribe to The People’s Friend! Click here

On the rugged shoreline of this forgotten isle, Catriona had met her kindred spirit...

Illustration: Sailesh Thakrar.

HISTORICAL SHORT STORY BY CHARMAINE FLETCHER

In this story, set in 1880, On the rugged shoreline of this forgotten isle, Catriona had met her kindred spirit…

Catriona Sinclair glanced around, awaiting the boat’s impending arrival.

There had been no cordial welcome for her when she’d first arrived on Alba, just a few curious faces, the lingering remnants of the Neal family, crofters charged with caring for her.

Even then, she was “neither fish nor fowl”, as Shona Neal, the matriarch, had said, and they hadn’t known quite how to treat her.

This time, she was determined it would be better.

Gulls cried in the distance, their sound mournful and haunting.

The wind was fashioning blonde streamers from Catriona’s hair.

How would Selina find such desolate surroundings?

Moreover, what of Catriona’s own plans?

The ones she and Sandy had made for her future were, due to her cousin’s predicament, in disarray.

As Angus Neal, Shona’s husband, lifted the child from the boat, setting her down, Catriona extended a hand to her new charge.

Motionless and rigid, she refused it.

Instead, the girl looked past Catriona to the stretch of fine, bleached sand, a fleeting, secretive smile crossing her face.

The “moon child”, as she was known, had arrived.

“As you please.” Catriona sighed.

Sadly, she dropped her hand, adjusted her paisley shawl and strode towards the house, turning occasionally to ensure her small cousin was following.

It was a phrase she would often use during their one-sided conversations.

While she was sympathetic, the child’s elective silence became increasingly frustrating.

Catriona frowned, watching Selina from her bedroom window one evening, skipping in and out of the watery light, pausing sporadically, staring out to sea.

Selina was so otherworldly, it was little wonder the family had abandoned her on Alba, a remote island off Scotland’s west coast.

Catriona recalled, from 11 years before, heated arguments and hushed conversations her relatives assumed she couldn’t hear.

Yet, in the gloomy recesses of her aunt and uncle’s cold, dismal house, young Catriona had tilted her head to listen.

“Tragedy or no’, what with her parents dying of influenza, she cannae stay here,” Aunt Mary had stated firmly, “especially with us so recently

married . . .

“She isnae our child – an’ she’s no’ like us, or anyone else, either! Catriona’s different!” she had spat.

Whom was she like, Catriona had wondered, if not her family?

Agnes, her elderly nanny, had explained in that matter-of-fact way of hers.

“It’s the ‘sight’, hen. Ye have it and they dinnae; I’ve seen it, so I know.”

Catriona recalled the looming, liquid figures at the end of her bed, the far-off children’s voices in the corridors and the soft woman’s keening in the empty attic bedroom.

Everything had been so vivid. How strange that nobody else heard or saw anything – including her parents.

“Hush now, dearest,” her mother had soothed. “It’s just your imagination.”

But Catriona had seen the meaningful look Mama and Papa exchanged.

They’re city folk, they dinnae understand such things,

Agnes had continued, “so they shove it away instead.

“But ye have the gift, like yer granny.

“People dinnae like talk of ‘seeing’ things: spirits, bogles and suchlike, shadows that aren’t. They’re afeared of folk being different, d’ye ken, Miss Catriona?”

At that time, Catriona wasn’t sure she had understood.

Now, she realised that people invariably dismissed what they couldn’t explain.

But finding something distasteful was one thing.

Banishing an innocent child, bereaved of their parents, was another.

Yet here, on the island, she’d been accepted.

Perhaps Selina would be, too, but how – and what about Catriona’s own life?

Several months had passed since her cousin’s arrival.

Despite Catriona’s efforts, the girl never spoke, simply gazing into the distance.

She was unwanted, unloved and misunderstood; once again, the island had served as a conveniently discreet depository for the Sinclair family’s supposed “misfits”.

Yet it was as though the poor girl didn’t seem to belong. It was as if she felt detached.

Initially, Catriona had assumed it was shock.

Losing her parents in the Tay Bridge rail disaster, leaving the child grieving and alone, was doubtless devastating, but it was more than that.

The pale, fey, silvery-haired five-year-old was named Selina, for the moon. Like a shaft of light, she was slight, her movements minimal.

Selina was enigmatic, enchanting, enchanted . . . apparently able to see things that others didn’t.

If it hadn’t been for her solicitor Sandy Rintoul’s letter and wise counsel, Catriona would have despaired.

Sandy’s father, Murdo, had been her parents’ solicitor, writing sporadically – Christmas and birthdays – to assure himself of her continued welfare.

Later, he began sending her books: poetry, novels, geography, history and newspapers, alas, out of date.

On his father’s death, Sandy had taken over the practice in Edinburgh.

After exchanging letters, Sandy had visited.

Quite unlike his father, he was tall and handsome, with a lively wit.

Catriona had listened, enthralled, and they had agreed her departure from Alba, but then they had received notice of Selina’s imminent arrival.

Any arrangements had had to wait and, disappointingly, she was making no headway with the child.

Finally, recalling his invitation to consult him in confidence, she’d written to Sandy. His reply came the next month.

My dear Catriona,

I found it astonishing, that your aunt cast you out simply for being a fanciful girl with a lively imagination.

Equally troubling is that your cousin has suffered the same fate.

Show me a lonely child without imaginary friends.

As to ghosts, well, is not Edinburgh the most haunted of cities?

Indeed, I firmly believe that there is more to this world than ether, yet it is only the lucky few who see as well as believe it.

Regarding concerns about your cousin.

Some people are naturally taciturn and, of course, she has suffered a terrible shock.

The Tay Bridge was an avoidable, devastating catastrophe.

It’s hard enough for an adult to grasp, let alone a child, suddenly without parents.

All she needs is love, compassion – and time in which to heal.

In the circumstances, who better to provide them than you?

I am glad you felt able to confide in me and, possibly, embrace what comfort I have offered.

There is also the matter of your inheritance, to which you are fully entitled, having come of age.

It will help fund the many experiences, so far denied to you, that you clearly deserve.

When it is appropriate, I hope you will allow me to show you such a life.

Nothing would give me greater pleasure.

Your friend,

Sandy Rintoul.

Catriona smiled wistfully.

Sandy had unlocked a Scotland beyond Alba and, with his gentlemanly charm, her heart, too. But he had also presented her with a dilemma.

She couldn’t stay on the island, Catriona thought.

The Neals were elderly and Alba was bleak, especially in wintertime.

Barely touched by life beyond its rugged shoreline, strangely, time appeared to stand still.

Catriona knew it had not.

There was a world waiting for her and Sandy Rintoul had awakened her memories of it.

Parks, museums, galleries, theatres and shops spun tantalisingly before her eyes, occupying her dreams.

Her parents had attended balls in Edinburgh and the opera in London – it all sounded magical, yet, unlike illusions, it was no longer out of reach . . .

If, like Grandmama, she was careful about mentioning the “sight”, Catriona might live in the Scotland she remembered: kaleidoscopic, energetic, alive . . .

Then Selina had appeared, complicating matters.

Catriona’s gaze returned to the child, a dot on the horizon.

Selina often wandered on the deserted beach, sometimes spinning and dipping with the gulls, on other occasions, still.

Was it then, perhaps, that she, like Catriona, had first seen them – the trio of ethereal couples dancing?

Gliding gracefully in the moonlight, the men wore tail suits, the women white dresses, tiny reticules a galaxy of shimmering stars, swinging on their wrists.

Selina was also dancing; a dappled, pearlescent figure on the inky shore.

Evidently, Selina saw them, too.

Careful to avoid asking the Neals, yet intrigued by the dancers, Catriona had discovered their story in a local history book.

Before they had turned sheep on to it, Alba had been a playground, of sorts, for younger Sinclair family members.

One summer, a party was held at Sinclair Hall, their estate on the mainland, just over the bay.

Someone had decided it would be amusing to sail out to the island and dance on its moonlit shore.

The night was mild and the waters calm. Soon, they were hand in hand, lost in the music of the sea.

Then, almost before they realised it, a ferocious storm had blown in from nowhere. The boat’s moorings had detached.

Marooned, the dancers were unable to reach shelter, the remains of a tumbledown bothy.

By the time they were noticed missing it was too late.

Understandably, the pull of Alba’s wild beauty was sometimes irresistible – dangerously so, Catriona concluded sadly.

Now, though, she wondered if there was more to it.

Perhaps they were not merely “moon shadows”, fragments of years gone by, but told a story straddling both worlds.

Were they, Catriona wondered, more than a link to the island, an ancestral property and its past?

Could they also be a portent of the future?

Why did they continue dancing when the moon was full, illuminating a velvet sky as the tide ebbed, pulsating hypnotically?

What had they been telling her, and now Selina, these mysterious shades, lingering, seemingly celebrating life long after it had forsaken them?

Slowly, Catriona smiled.

She understood, at last, the reason they kept reappearing to dance in the moonlight.

They were telling her to leave the island while she still could, before it was tragically too late, as it had been for them . . .

Only, what of Selina?

Making her way along the beach, Catriona watched Selina’s small feet tracing the pattern of the dance in the sand.

Abruptly, the girl halted, staring at Catriona.

Then, echoing the slow manner of the dancers, Catriona swayed to the time-remembered rhythm.

Gradually, Selina beamed, extending her hands to Catriona, who enclosed them in hers.

How they danced!

Their footsteps travelled to the music of the rolling sea, rising, sinking and turning.

They were splendidly at one until, tired, they stopped, scanning the sky, then the shore.

The moon sank beneath darkening clouds. The wind, but a soft breeze, stirred.

A whisper of silk, and the dancers disappeared.

Companionably, Catriona and Selina, the moon child, walked home, knowing this time it didn’t matter where that was . . . if they were together.

Never miss an issue ‘The People’s Friend’ packed with even more stories on sale every Wednesday.

Deborah Siepmann

Alison Carter

Teresa Ashby

Beth Watson

Alyson Hilbourne

Katie Ashmore

Kate Hogan

Liz Filleul

Beth Watson

Alison Carter