Far From The Island – 26

Far From The Island

« Previous Post- 1. Far From The Island – 01

- 1. Far From The Island – 26

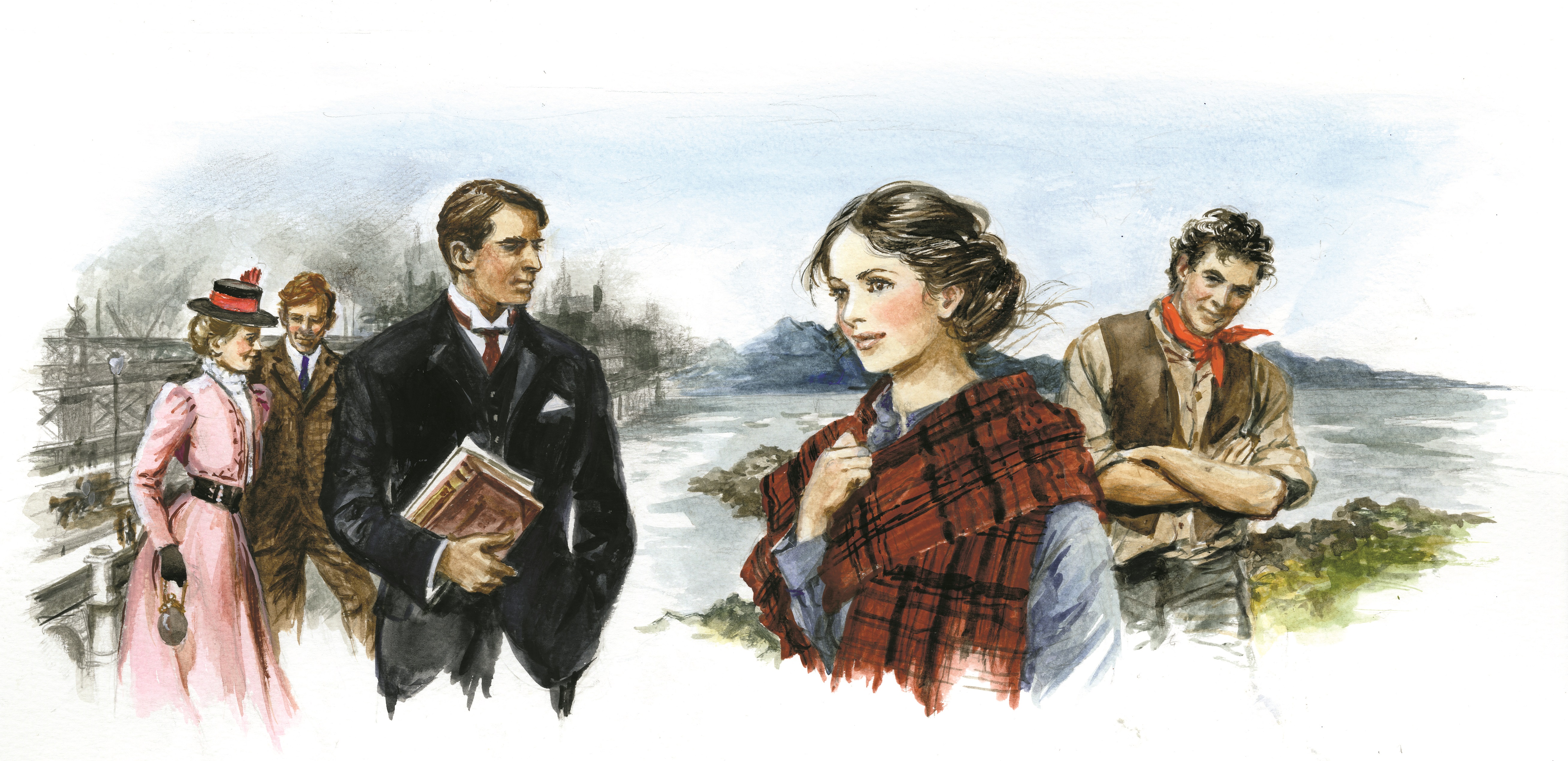

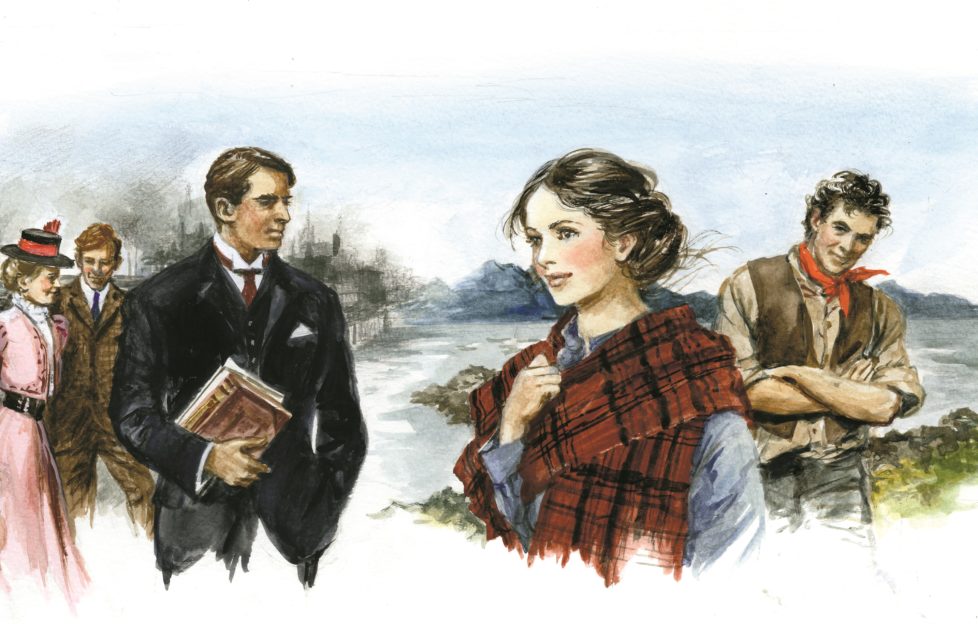

It struck Fiona every time how different these people were from the Cunninghams. It wasn’t just that they were so friendly and so grateful, but it was the way that they got on with the very raw deal life had dealt some of them. Last Sunday, Matthew had taken her on a walk around the streets of Govan.

It was Fiona’s first experience of true poverty, and she’d been appalled at the dark and dingy tenements, built so closely together that the limp washing was strung out on lines stretching across the alleyways. It was a million miles from the wide-open, windswept spaces of Heronsay, and yet there was a similarity in the people’s resilience, their tight sense of community. Their pride.

“Though the parish health officer does his best to act on the reports of the sanitary officers,” Matthew had explained, “forcing the landlords to comply with the recommendations is an uphill struggle. Some of the back courts still have ash pits and middens, despite the fact that we know for sure that clearing them out and installing proper communal sanitation has an incredibly positive effect on health.”

Mortality rates, cholera and the spread of infection due to the chronic overcrowding: Matthew spoke with an evangelical enthusiasm about his plans for eliminating them all as they walked through the crowded streets. Around them, children skipped and played, while women sat on the doorsteps watching, nursing their babies. Most of the doorsteps were scrubbed clean, Fiona noticed. Despite the smoke-filled air and the lack of a good drying breeze, the quantities of washing on the lines spoke of the women’s determination to keep their standards high.

“Doctor Usher wants to see you before you leave,” Nurse McEwan said at the end of another busy day, as Fiona tidied herself in readiness for the journey back to the prosperous West End via the dreaded subway. To think it even went under the Clyde. No, best not think about that!

Most likely Matthew wanted to ask her for a progress report on Francis, Fiona thought as she tapped on the door of the consulting room.

The doctor was sitting behind his desk. His hair was dishevelled. He had a habit of running his fingers through it when he was thinking. Euan used to do just the same thing, Fiona remembered with a little stab of pain. She used to reach up and pull his hand away, smoothing down his curls. He would smile at her when he did that, a lop-sided smile that she always found endearing.

A pang of homesickness washed over her for Heronsay, but she gave herself a little shake, and smiled brightly at Matthew, who had jumped up from behind his desk.

“I was worried you’d already left.”

“It’s been a busy day. Nurse McKinley taught me how to listen for the babies’ heartbeats. It was wonderful.”

“You’d make a fine nurse, Fiona. I’ve said it to you before – you should think about formal training. Francis won’t need you for much longer, and then . . .”

Matthew took her hands between his. His fingers were warm and long, the nails cut close and immaculately clean. He looked nervous.

An answering flutter started up in Fiona’s stomach.

“Matthew? What are you trying to say?”

“I thought that if you trained as a nurse, you might like to work here, at the clinic.”

“I – yes,” Fiona replied uncertainly, confused and strangely disappointed.

“With me, I mean,” he continued.

“Oh.”

Matthew took a deep breath. His fingers tightened around hers.

“Fiona, you must know that I . . . that I want to . . . that I think we could . . .” He broke off with a rueful smile. “Fiona, what I’m trying to say is, I’d like to take you home next Sunday. To meet my parents.”