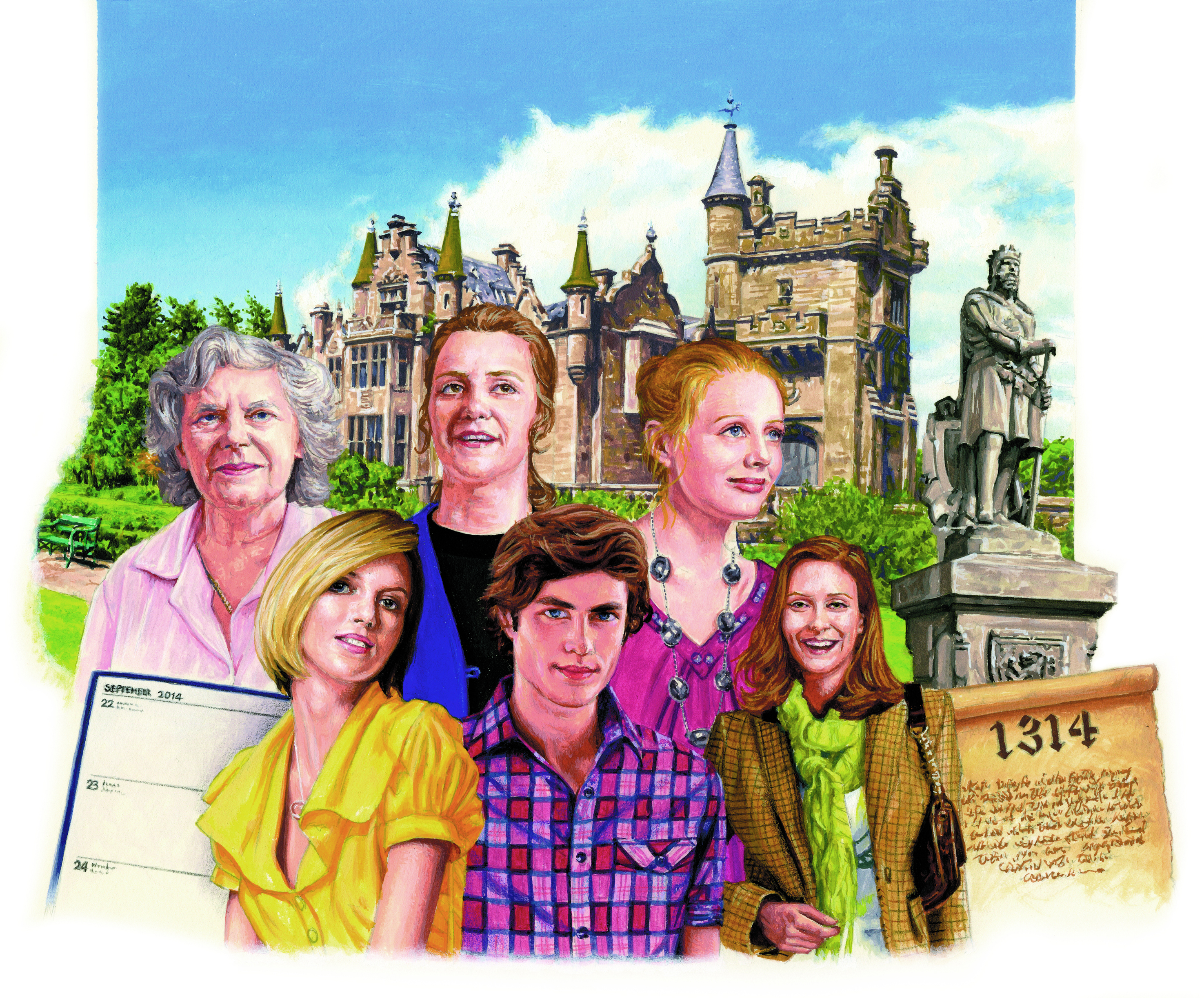

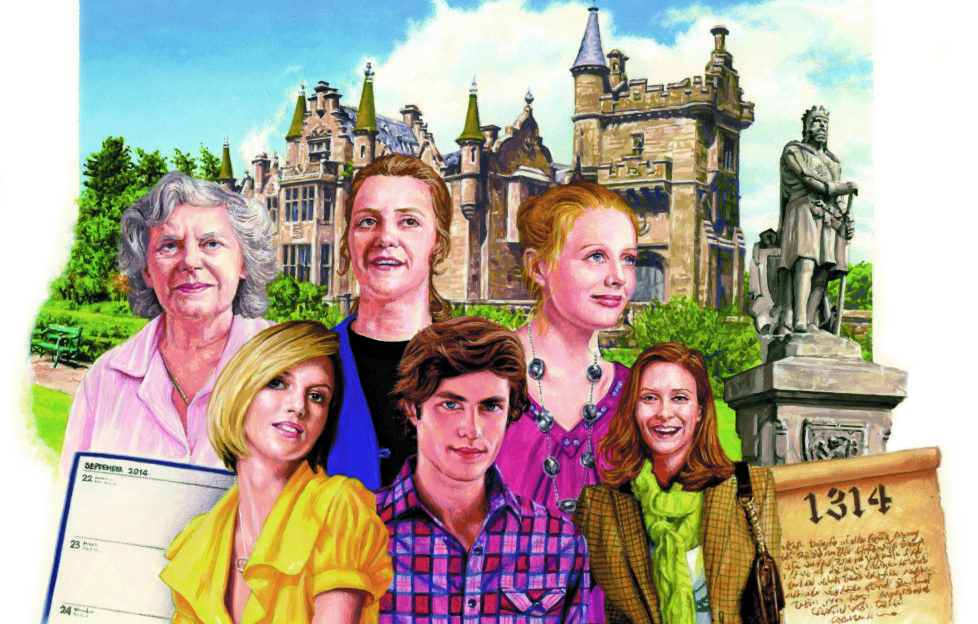

Echoes From The Past – Episode 18

Echoes From The Past by Joyce Begg

« Previous Post- 1. Echoes From The Past – Episode 01

- 1. Echoes From The Past – Episode 18

Mirin spent a terrifying day behind bars in splendid isolation. She could hear the voices of other prisoners, yelling their frustration and pleading both innocence and starvation. The very idea of being there for any length of time sent shivers of terror through her. She tried to convince herself that her father would somehow get her out, or that Thomas would bring English authority to bear on the sheriff, but frequently the terror won. Sleep that night was fitful and shallow, lying as she was on a bit of sacking on the floor. She was almost relieved when the sheriff’s men came back for her in the morning, and carried her by the elbows into the court.

The court was a large room with wooden panelling, and in normal circumstances would have looked handsome rather than threatening. The sheriff at last came in, and sat in his high official chair, surrounded by men in black who chattered about legal proceedings in such cases. Mirin looked wildly round, trying to find a known face in the well-filled benches. Word had got around that Mirin of the Black Cockerel had been accused, and all sorts of people had come to view the scene. Some were faithful customers, and others were strangers. At last she saw her father, restrained at the back of the room by two more strong men, and threatened with removal if he opened his mouth. And in the far corner, swathed and cowled in black, was the thin figure of Petrus, the Dominican friar.

The sheriff – an imposing man with ferocious brows – looked down at Mirin, standing before him trying very hard not to shake.

“Mistress Mirin, daughter of Hector the publican?”

She cleared her throat and said, “Yes,” as defiantly as she could.

“And according to the paper here, you are accused of witchcraft.”

“I am no witch, sir. Who accuses me?”

The sheriff raised his brows.

“A good question.” He turned to the lawyer nearest to him, and repeated it.

“The accuser is not here, Your Honour.”

The sheriff’s brows came down.

“You have brought me here to make a judgement according to the law, and you have no accuser?”

“We have an accuser, sir, but they wish to remain anonymous. They fear that the witch will exact a revenge.”

The brows went back up again.

“I suppose that’s possible. Could the person be sitting in court, watching to see justice done?”

Everyone, including Mirin, looked about them. Only one person looked straight ahead, his burning gaze focused on Mirin herself. Friar Petrus.

Her attention was brought back to the sheriff, who again looked towards the lawyers.

“Are there any witnesses?”

“None, your honour. Only the accuser.”

The sheriff chewed his cheek thoughtfully, and then spoke to Mirin.

“Do you have anyone to defend you, girl?”

The terror that had seized Mirin ever since the sheriff’s men had come for her was suddenly transformed into anger. How dare anyone do this to an innocent citizen? Was this the Scottish law that people were so proud of?

“I have not, Your Honour. I was taken from my home, put in a cell, and given no chance to speak to any lawyer, or indeed anyone else.”

“Then you must defend yourself. That is the law.”

“Then I will.” Mirin straightened her shoulders, rage making her resolute. “Of what exactly am I accused?”

She had no idea what to expect, her mind spiralling off into realms of bringing down curses and changing people into animals, which her brain told her were lunatic inventions. But how does one defend oneself against lunacy?

The sheriff looked again at the paper in front of him.

“You have been heard to recite spells and charms, in magical gibberish.”

Mirin stopped dead in astonishment.

“Spells and charms?”

The sheriff looked at her from under his massive brows.

“You are here to answer questions, girl, not ask them. Have you been guilty of chanting spells?”

Suddenly, Mirin understood. She saw herself, in and around the Cockerel, serving up food and clearing up after customers, reciting under her breath the lessons Murdo had passed on from the monks. That could well sound like gibberish to the uninitiated. Confessing to learning Latin might get her off the charge of witchcraft, but it might also lead her into different troubled waters.

She had never thought faster in her life.

“I may well have been guilty of reciting recipes to myself,” she said. “My grandmother left me many of her recipes, some of which I use in the Cockerel kitchen, but others have to wait till the fruit comes into season. I recite them to myself in case I forget them, sir. Would that be what my accuser heard? Whoever he is, he’s a craven coward. Frightened of a granny’s recipes.”

That drew a murmur of laughter from the public benches. It looked as though the sheriff did not know whether to join in the amusement or object to levity in court, but before he could decide, there was a commotion at the main door of the courthouse. Something was happening that put Mirin’s trial completely in the shade.