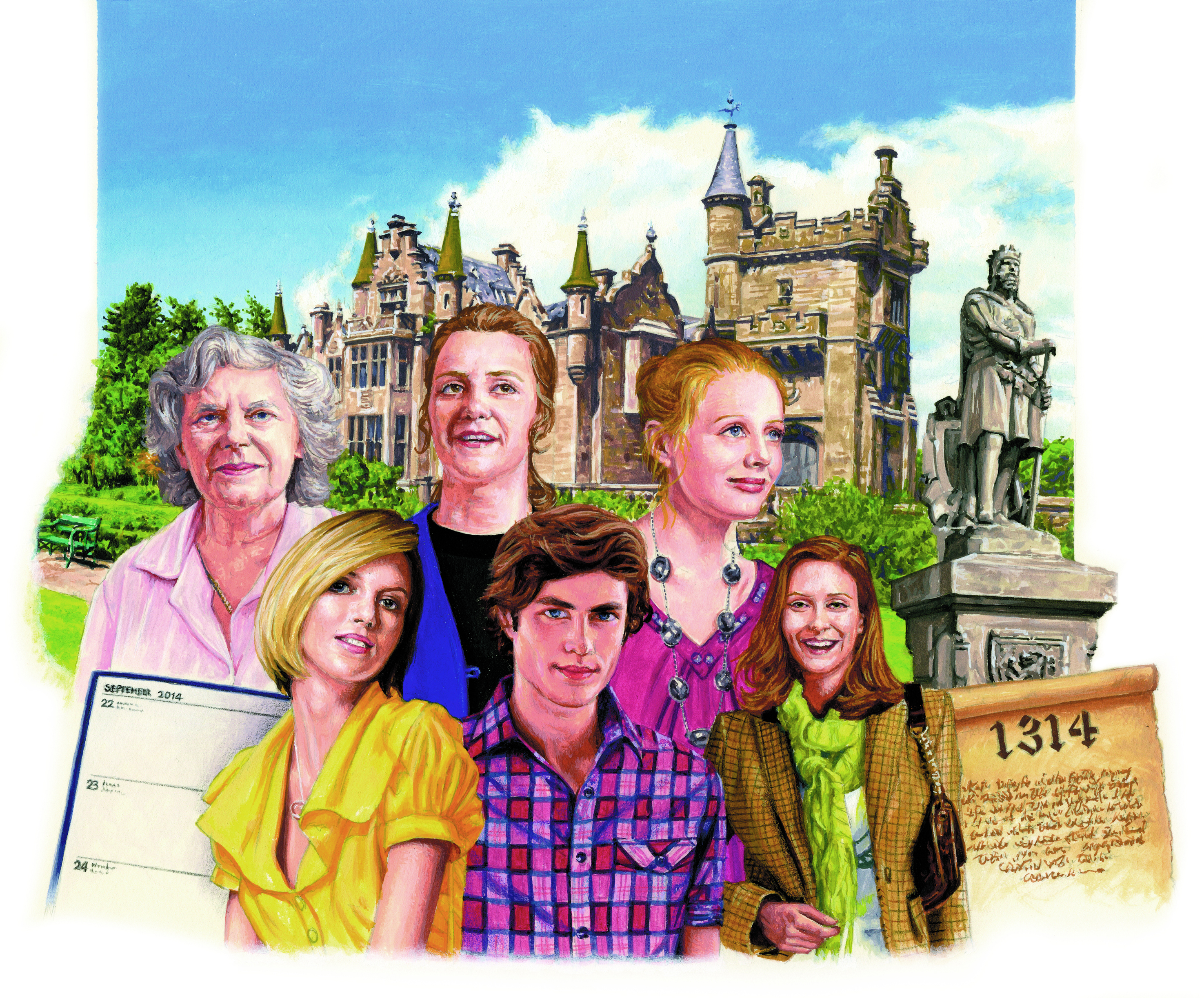

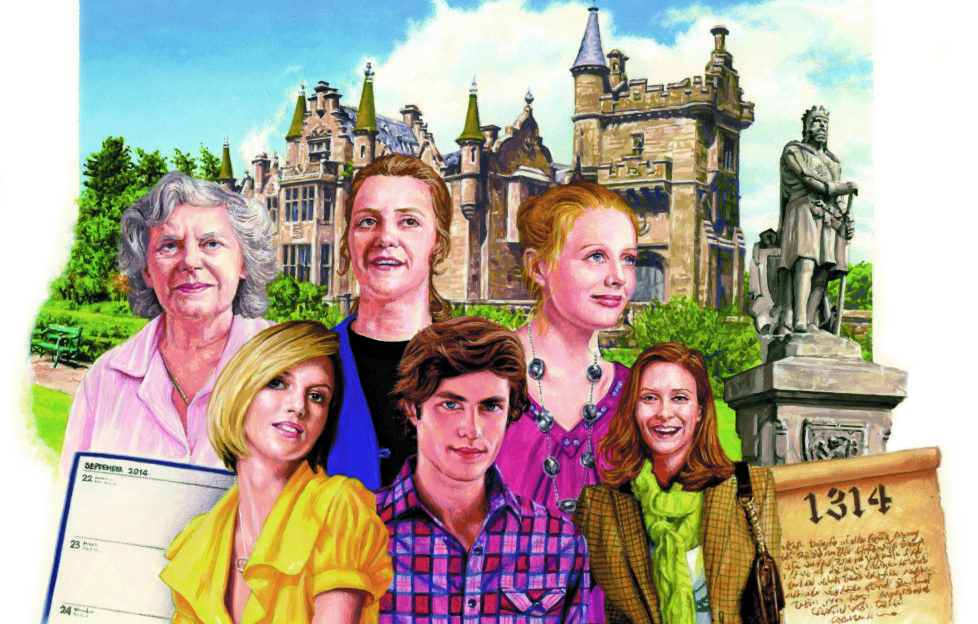

Echoes From The Past – Episode 05

Echoes From The Past by Joyce Begg

« Previous Post- 2. Echoes From The Past – Episode 02

- 3. Echoes From The Past – Episode 03

- 4. Echoes From The Past – Episode 04

- 5. Echoes From The Past – Episode 05

- 6. Echoes From The Past – Episode 06

- 7. Echoes From The Past – Episode 07

- 8. Echoes From The Past – Episode 08

Mirin was almost nineteen years old, and unmarried. Since the death of her mother some years before, she had been her father’s main support, both emotionally and in the running of the tavern. She had learned how to control men so that they didn’t realise it was happening. She bent and twisted and cajoled, and generally she won them round. The trouble with this kind of skill was that it did not attract a husband. For who would marry someone who, for all their good nature and good looks, could make men feel inferior?

But even Mirin was sometimes pushed to maintain the peace in the Black Cockerel. Usually, her father was on hand to rule the roost. Today, he was in the kitchen, a hot haven of simmering mutton and rough dark bread. The other occupant of the kitchen was Etta, there to scrub pots and keep the dogs out. She was as dim as Mirin was clever, thin and pale, and greatly given to superstition.

At Mirin’s call, Hector came through from the kitchen with bowls of steaming stew to quieten the workmen.

“There you are, Joseph. Get that down you. And no complaints, mind. That’s good stew.”

Fortunately, Joseph was too hungry to argue. Hector stood over them for a moment, then turned to view his other customers. He was a square man of medium height, with square shoulders and square hands. His face was a mask of polite indifference. He didn’t care for the English, but he needed their money. It was the same all over Stirling.

It was inevitable, once Joseph had been fed and Humphrey had consumed another tankard of ale, that sparks would fly. Joseph’s friends were calmed by the meat and bread, but it seemed to have the opposite effect on the cobbler. It gave him strength and confidence.

“There’s a terrible smell in here today, Mirin,” he said, as she passed to take food to Pate Joiner. “Could it be the smell of Englishmen?”

“Well, it’s not the mutton,” Mirin said sharply. “It could be the smell of the tannery, which everyone knows stops the nose entirely.”

Although it was a quick retort, it was not a wise one. In spite of the differences in the way the Scots spoke, Humphrey and Thomas picked it up and laughed spontaneously. Even Joseph’s friends found themselves covering their mouths. It was an insult to the soutar’s profession, but at the same time, there was no doubt that anyone who dealt in leather ran the risk of smelling of the tannery.

Joseph’s complexion turned an ugly red. He jerked to his feet, filled his chest like an angry bull, and set off for the soldiers’ table.

“You, Englishman,” he shouted, pointing a finger at Humphrey’s chest. “You find that funny?”

“Yes, indeed,” Humphrey replied, smiling affably but with a glint in his eye. “So did everyone else. Look around you. Even the old pair beside the fire are trying not to laugh.”

By the time Joseph turned round, the old pair had their heads down over their plates. No-one could have told if Humphrey was right or not. Joseph swung back again.

“No-one laughs at me, English,” he said.

Humphrey felt compelled to respond. In spite of Thomas’s restraining hand, he got to his feet, and made the mistake of prodding the cobbler in the chest.

“I do laugh.” He grinned. “So does everyone else. You are a fool, man.”

It seemed it was a day for mistakes. Instead of backing down, Joseph responded with a punch to the Englishman’s face. A soldier with Humphrey’s experience should never have been caught out so simply. He responded with a blow to Joseph’s chin, which sent him reeling back to the table and the friends he had just left.

By normal holy day standards, it was a mild enough affair, but it took Hector and Mirin some time to restore order. They were helped, it had to be admitted, by Thomas, who, once he had floored one of Joseph’s companions with a blow to the midriff, concentrated instead on getting Humphrey to desist before he resorted to using his sword.

In that respect, Hector knew he was indebted to the Englishman. There would be no blood-letting that day in the Black Cockerel. But the threat was there. As the soldiers stood in the doorway, they were lit up from behind by a sudden shaft of sunlight, so that the motley crew of bruised and battered local men saw them for what they were – the embodiment of a foreign power, over which they had scant or no control.