A Quiet Honeymoon – Episode 09

A FEW days later, Ruth asked Mary Greville to meet her in Bosham to take tea beside the quay. Mary Greville arrived in her father’s carriage, looking lovely in a pale green dress, her tiny waist emphasised by a grey sash.

“You look to be in better health, Miss Greville,” Ruth said.

“I believe I am, Mrs Greene,” Mary said, sitting and hanging her parasol from the chair back.

They ordered tea and talked about Sussex.

“I think there is a zoo at Chichester,” Ruth said. “Is that right?”

“I don’t believe so,” Mary said.

“That’s a pity. I enjoy a zoo. You mentioned the zoo at Edinburgh.”

“Oh, yes, I did,” Mary said.

Ruth frowned.

“I have a dear friend from my student days, Elspeth, who comes from Edinburgh. She tells me that the zoo at Edinburgh was opened quite recently, in 1913.”

A splash of tea fell from Mary’s cup on to her dress.

“I must be thinking of another attraction there,” she said.

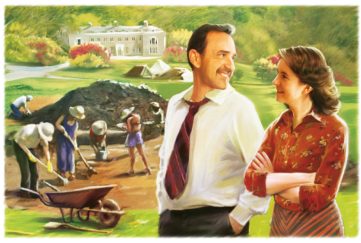

“A zoo is a very particular thing.” Ruth smiled. “But we all forget details. Mr Greene and I observed, for instance, as we left your house by the lane gate, that it is easy to hear what is said on the other side.”

Mary was dabbing hard at the tea stain with a handkerchief.

“It is almost as though,” Ruth went on, “that when you came across us that terrible day, you knew we were there because you did hear our voices, that you wanted to burst out upon us, and show a pair of strangers how shocked you were to find Mr Quirk dead. I could almost have believed that you were acting a part.”

Mary Greville stood up. Her parasol clattered noisily to the ground.

“I cannot imagine,” she said, “what you are implying! I have never acted in my life, and I cannot recall every visit to every zoo, or ”

“Miss Greville.” It was Terence who spoke, walking across the teashop floor from a distant table. “I think that I may have something of yours.” He laid the letter on the table. Mary looked at it.

“Are you Dolly?” Ruth asked.

Terence sat down next to his wife.

“Sergeant Brown’s men had to find a bed for the night for a certain old lady. She was lying in the church porch at Brakenham. After some persuasion, she said that she was a Mrs Mabel Jessop of Brewer Street, in Soho. We know, Mary, that you are called Dolly Walters, not Mary Greville. And we know a good deal more.”

Dolly Walters sat down.

“She’s a filthy old thing,” Dolly said in a low, angry voice. “I’d like to have ended my association with that woman years ago, but she does harass me so. She came here, then? Chasing her fees.”

“Why don’t you tell us your story, Dolly?” Terence said.

The young woman glared at them both, and set her mouth in a hard line, but after a minute her shoulders slumped.

“I suppose you know most of it,” she muttered. “Sarah Francis Sarah Greville she died as soon as her daughter was born. She’d got as far as Soho. Mabel Jessop saw her die. Mabel placed her child, baby Mary, in an orphanage, a place from where they pass on girls for service. They often end up in the colonies, I believe.”

“India, in the case of Mary Francis,” Ruth said softly.

Dolly took a long drink of tea.

“Jessop’s trade is fraud,” Dolly went on. “She went to prison for it soon after, but when she got out she saw her chance. I was ten years old then, my own father in prison and my mum . . .” a flush passed across her face “. . . liked the opium. Mabel Jessop saw that I looked like Sarah Francis the fair hair and knew I might be passed off as Greville’s child. There was a lot of work to be done stories to create. I had to be trained. Jessop had done it before. In this case, she knew the name of the family and the village, all from Sarah’s story.”

“What about Sarah’s funeral?” Terence demanded. “You went with Mr Greville to Edinburgh.”

“A fake,” Dolly said. “You can find a crooked minister if you look hard enough.” A look of pain passed over her face. “I would gladly have spared him that.” She looked at both of them. “Matthew Greville is a good man.”

Tears ran down her cheeks.

“And Mabel Jessop expected payment.”

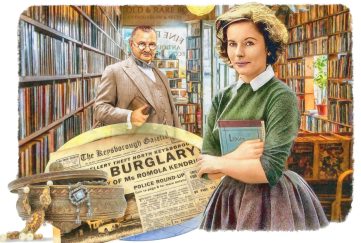

“Four times a year, beginning a year after I came here. I received an allowance when I was thirteen. Mr Quirk handed it out. I shared it with Jessop. Oh, I should have burned every letter!”

“So, Mrs Jessop came lately with demands?”

Dolly nodded.

“She wanted more. She was growing too arthritic for her usual career of petty crime. She was looking for a pension.”

Dolly seemed about to try to leave, and Terence stood and restrained her.

“Sit down,” he said, and she sat.

“Mary Sarah’s real daughter,” Ruth said, “met a young man in India, married him, and returned to England.”

“I know nothing of that,” Dolly said.

“She had a picture,” Ruth insisted, “and the story of her father, and she thought perhaps, now she was to have a child of her own, she might see him. You heard of her arrival. You were trained by Mabel Jessop to be vigilant. How did you hear?”

“Hear what? I don’t know any other Mary.” Dolly’s eyes were fixed on her teacup.

“Did you pay to have her drowned in the sea at Bosham?” Ruth said softly. “Is that the expenditure which James Quirk knew about? What money did you take from the household, and how?”

At the name of James Quirk, Dolly flinched. Ruth glanced at her husband.

“Sergeant Brown,” Ruth said, leaning across the table towards her, “enquired among the ironmongers of Chichester, Dolly. A man in Chapel Street reported that a fair-haired young woman bought a spade only a few days ago.”

Terence sighed.

“You smudged a new spade with dirt. It was nicely done. You will have to tell Sergeant Brown, Dolly, who drowned Mary in the sea at your behest.”