A Quiet Honeymoon – Episode 07

THE following day they walked to East Wittering and to the butcher’s shop there. Inside, a very fat woman with red arms was hanging sausages on hooks from the low ceiling. The sleeves of a vast white blouse were rolled up past her elbows. An old man with a noticeable lack of teeth and a jacket too large for him leaned against a wall.

“Good morning,” Ruth said.

The woman smiled.

“What can I get you?” she asked. “We’ve nice fat chickens, just in.”

“We are thinking,” Ruth said carefully, “of some game.”

She frowned.

“It’s not the season for it, dear. We might have game come September.”

“Where do you get your pheasants from?” Ruth asked.

At that moment the old man sprang out with surprising agility from his place against the wall.

“Are you come from that nuisance they call Quirk?” he said.

Ruth looked startled.

Terence stepped forward.

“I am sorry to have to tell you, Mr . . .” he looked expectantly at the man, waiting for a name, but the man only sniffed, and rubbed a greasy sleeve across his face. “I am sorry to have to tell you that Mr Quirk ”

“Mr Quirk is a prig and a gossip,” the man said. “He should keep himself to books and ledgers. He ”

“He’s dead,” Terence said.

The man’s eyebrows lifted for a moment. They heard the fat woman whistle.

“Is ’e?” the man said. “Well, maybe that’s what happens when you go poking around among your neighbours.”

“What happened to him?” the woman asked. “When?”

“He was murdered, in Brakenham, three days ago.”

“The police will be establishing,” Ruth said casually, “where his neighbours were that night.”

“That was Saturday, then?” the butcher said. “I don’t know why I should tell you, but I was at a church meeting here, in the room next to the church.”

“Were you there, too?” Terence asked the man.

He snorted.

“Not likely,” he said. “I can’t remember where I was and I’m not about to share my engagements with you.”

Ruth and Terence turned to go, but the man blocked their path. He smelled none too sweet in the cramped environment of the shop.

“I never killed anyone,” he said, “though I might have brought down a bird or two. On Saturday I was at ’ome, and I live on me own, before you ask, between here and West Wittering.”

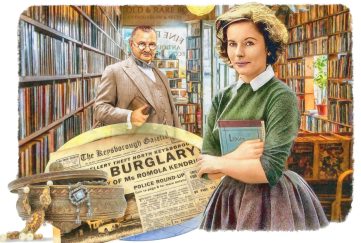

Next, Ruth and Terence called in at the Wittering police station and reported their findings to the stout sergeant.

“Sergeant Brown,” Terence asked, “did your men establish the weapon with which Mr Quirk was killed?”

The sergeant assumed an expression of professional efficiency.

“The quantity of blood,” he said, and then shot a glance at Ruth. “Would Mrs Greene prefer to wait in ?”

“Mrs Greene,” Ruth said firmly, “is perfectly able to listen.”

The sergeant looked doubtful.

“Well, the quantity of blood indicates several blows. We found nothing at the scene. My own view is that the object used had . . .” He looked uncomfortable again, and gave Terence an imploring look.

Ruth rolled her eyes.

“I will wait for you outside,” she said to her husband.

Terence joined her five minutes later.

“The weapon, Sergeant Brown believes, had a blade, but not a sharp one.”

“A farm implement,” Ruth suggested, “or something similar?”

“He is sending his men as many as he has in a small station to the farms inland.”

“They must focus on motive,” Ruth said firmly. “It is always motive.”

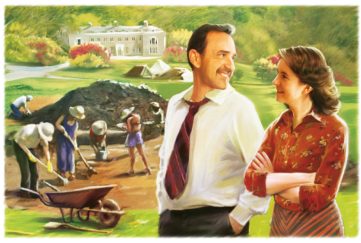

Feeling that their investigations, at least for now, had stalled, they walked homeward. They were engaged to dine with the Grevilles early in the evening.

Mr Greville had sent the invitation that morning, explaining that Mary was very tired, but that they valued the company of their new friends, who had some understanding of their present distress.

Mr Greville sent a carriage in very good time, and they were nearly 45 minutes before the appointed hour. They thanked the driver and said that they would alight on the edge of the village and walk along the stream to the house.

“You look particularly beautiful this evening,” Terence said to her as they strolled. “I am a very fortunate man.”

She laughed.

“Let’s look at the stream here,” she said. “It’s very pretty, and we never got to complete our walk in Brakenham. We must not, anyway, be early for an appointment with such smart people.”

They made their way gingerly down the bank to a tiny stretch of sand.

“It’s a fairy beach,” Ruth said, smiling, “barely large enough for my shoes and for your great policeman’s boots.”

Terence looked offended.

“These are my wedding shoes,” he said, “and cost nine shillings flat!”

“Flat is precisely the word!” Ruth laughed out loud. “What’s that on the other side?” she said, pointing to a tangled mass of undergrowth, four feet from them on the opposite bank.

“What?” Terence asked.

“Look, it’s too straight to be vegetation,” Ruth said. “We need to examine anything unusual.”

“We are about to dine with such smart people!”

“You won’t get very damp,” she said.

“Well, evidence comes first,” Terence said with resignation. He took off his boots and socks and handed them to Ruth with a wry smile. With his trousers rolled and his ankles exposed, he waded carefully across the stream, and pulled out a garden spade. Its handle was broken off. Only the post had been protruding out of the reeds. Terence held it up as he re-crossed the stream.

“Blood?” Ruth said, squinting into the evening sunlight.

“Why must I have such a gruesome wife?” Terence asked as he landed. They both looked at the spade. “If there was blood, it has been washed away,”

“It’s been buried among the undergrowth. There’s no rust, so not for long. But where does this come from? How far are we from the lane?” Ruth asked.

“Only a minute at a trot,” he said.

“Our murderer might have used this, fled, and thrown it into the stream as he went. Perhaps he thought it would sink to the bottom. It’s deep enough.”

Terence looked down at his trousers, soaked to above the knee.

“Then he threw it too far,” he said. “He did not know his strength.”

He carefully exchanged the spade for his shoes.

“Now we are late,” he said.