A Quiet Honeymoon – Episode 02

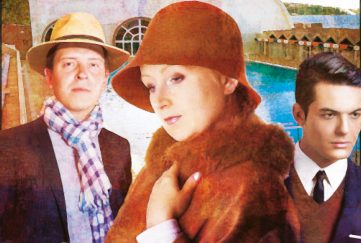

THEY settled on a trip to West Wittering in Sussex. A relative of Mrs Rutherford recommended a boarding house close to the sands, and sent a guidebook as a wedding present. Ruth gazed on the picturesque quayside and declared the place ideal.

So there they were, with the week’s holiday ahead of them. Terence demanded that they visit no churches that day. They sat and drank morning coffee in a public house in West Wittering. Terence read the local paper, and Ruth said he looked like an old married man.

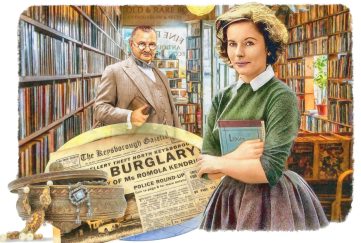

“Here’s a sad thing,” he said, laying the paper on the table, “and in such a quiet place as you say Bosham is.”

Ruth leaned in to look. On the front page was the photograph of a young woman.

“Drowned,” Terence said.

They both thought of their first case.

“Who is she?” Ruth asked.

He shook his head.

“They don’t know. The picture is published here to see if anybody can name her.” He folded the paper. “Very sad. She must be younger than you.”

“Scarcely twenty, I’d hazard,” Ruth agreed.

Later, they followed a footpath away from the coast for a mile or so until they reached a hamlet with a winding main street. A well-kept sign read, Brakenham.

“Now this,” Ruth said as they passed an ornate wrought-iron gate, “is a fine example of Tudor.”

Terence looked through the gate at the house. It was of a good size but not over-large, built of dark red brick, interspersed with blackened timbers. Tall, narrow chimneys gave it an elegant air. An old brick wall that enclosed the gardens of the house. Masses of ivy grew up the wall, and vigorous hydrangeas were just beginning to flower in a dense shrubbery below.

“Blue flowers,” Ruth said. “The soil here must be Oh, Terence!”

He had been lagging behind, thrashing at nettles with a long stick. He heard the note of distress in Ruth’s voice and hurried to her.

A pair of black shoes could be seen protruding from the hydrangeas. They were shiny, and old-fashioned in style.

Terence crouched, and carefully pulled back the shrubs. Ruth bent over his shoulder.

“Don’t look!” he said, but it was too late.

“So much blood,” she whispered. “His head!”

“He is certainly dead.” Terence sat back on his haunches. “The suit and shoes tell me he’s a middle-class man. He’s perhaps fifty,” Terence went on. “The blood is dry . . .”

“It was several hours ago, I suppose,” Ruth said.

“Yes, I think so. Perhaps last night.”

The man’s face was whole, but the back of his head had suffered terrible damage.

Terence looked up into Ruth’s eyes.

“Poor man,” she said.

“Indeed.” Terence let the hydrangeas fall gently back into place. “Now, it’s a tiny village. The nearest police with any skills for this will be Bosham, or even Chichester.” He stood up slowly and took her hand in his. “What was it your father said about our walking away from crime?”

“Impossible,” Ruth said briskly. “So now we must decide our next step.”

“Mr Quirk?” A woman’s voice was approaching, on the other side of the wall. “Tea is ready on the terrace, Mr Quirk.”

Ruth and Terence had not noticed an arched gate in the wall, six feet or so beyond the body. The heavy wooden door opened with a creak, and from it walked a pretty young woman, a little younger than Ruth, in a handsome summer gown of pale pink silk. She had very pale fair hair, pinned up under her hat, and shining blue eyes.

“Oh, good morning,” she said in mild surprise, seeing Ruth and Terence. She stood just outside the arch and looked from side to side, up and down the lane.

“Mr Quirk!” she called again, and then turned to Ruth and Terence. “You have not seen, I suppose, a gentleman? He is uncharacteristically late, and my father will be home shortly.”

Then she saw that they both looked shocked and her face changed.

“Are you quite all right?”

Her gaze followed Terence’s.

“Surely those are the shoes ” She looked at Terence, bewildered. Her face began to contort into an expression of intense anxiety.

“Do you think you know this gentleman?” Terence asked quickly. As the girl stepped towards the body, Terence moved instinctively towards her.

“Don’t look, miss,” he said. But she had been able to move aside enough hydrangea to see part of the face. All the breath seemed to go out of her.

“But it’s Mr Quirk.” Her voice fell to a whisper. “He is coming for tea.”

“I am a police officer,” Terence said, “with the Oxfordshire constabulary. I believe this man has been murdered, miss.”

She stared up at him, the colour draining from her face.

“No!” A sob escaped her throat. “How? Who would do such a thing?”

“If you don’t mind,” Ruth said gently, “my coming into your garden, I think it would be best if I escorted you away from here.”

She took the girl’s arm.

“Have you a servant who can run to fetch the doctor?”

The girl stared at her.

“Janet is making the tea. We have a cherry cake. I feel faint.”

The two young women made their stumbling way towards the gate.

“See if there’s someone to keep watch while I find the local boys,” Terence called.

Ruth and the girl walked past a small table laid with china, a vase of flowers at its centre. A pair of French doors was open at the house, and Ruth laid the girl on a sofa. It was a beautiful house, its furnishings simple and elegant and the room full of light. Through an open interior door, Ruth could see a spacious hall and a great open fireplace. She rang the bell, and explained briefly to the maid, who ran to tell the housekeeper, and then to fetch a doctor.