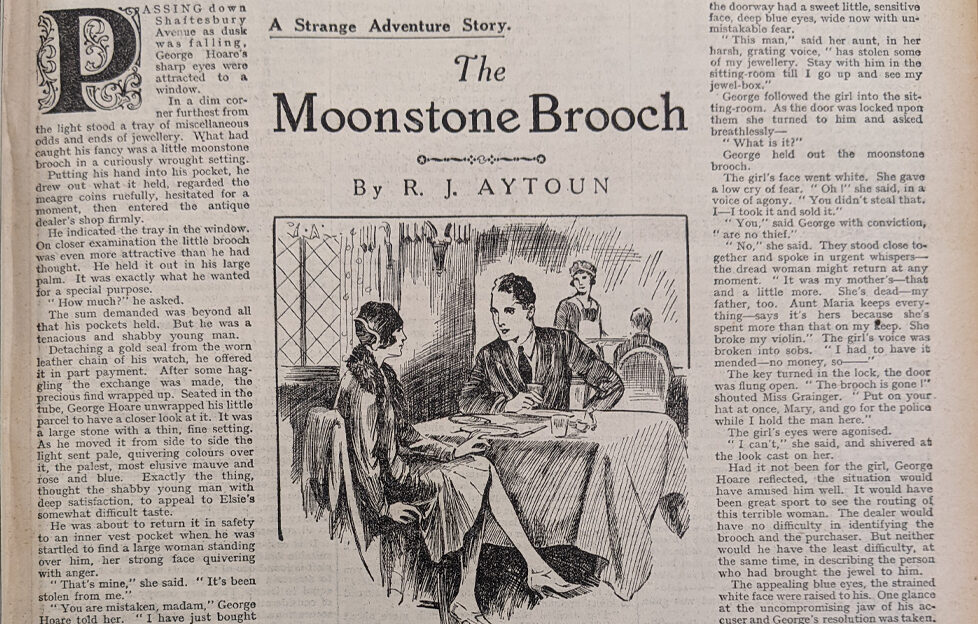

This episode of the Reading Between The Lines podcast is “The Moonstone Brooch” by R. J. Aytoun, first published in March 1, 1930. This “strange mystery” falls a bit flat with the team! Is it well written, or just a bit too daft? Listen along to the episode as you read and let us know what you think!

Passing down Shaftesbury Avenue as dark was falling, George Hoare’s sharp eyes were attracted to a window.

In a dim corner furthest from the light stood a tray of miscellaneous odds and ends of jewellery. What had caught his fancy was a little moonstone brooch in a curiously wrought setting.

Putting his hand into his pocket, he drew out what it held, regarded the meagre coins ruefully, hesitated for a moment, then entered the antique dealer’s shop firmly.

He indicated the tray in the window. On closer examination the little brooch was even more attractive than he had thought. He held it out in his large palm. It was exactly what he wanted for a special purpose.

“How much?” he asked.

The sum demanded was beyond all that his pockets held. But he was a tenacious and shabby young man.

Detaching a gold seal from the worn leather chain of his watch, he offered it in part payment. After some haggling the exchange was made, the precious find wrapped up. Seated in the tube, George Hoare unwrapped his little parcel to have a closer look at it. It was a large stone with a thin, fine setting. As he moved it from side to side the light sent pale, quivering colours over it, the palest, most elusive mauve and rose and blue. Exactly the thing, thought the shabby young man with deep satisfaction, to appeal to Elsie’s somewhat difficult taste.

He was about to return it in safety to his inner vest pocket when he was startled to find a large woman standing over him, her strong face quivering with anger.

“That’s mine,” she said, “It’s been stolen from me.”

“You are mistaken, madam,” George Hoare told her. “I have just bought and paid for it.”

“You can tell any story you like to the police,” said his antagonist violently. “You are coming with me now.”

The tube was crowded. The sensation began to spread.

An elderly man seated next to George said in a judicial and precise manner—

“It’s a serious matter to accuse anyone of theft, madam. You may involve yourself in a highly unpleasant suit.”

“The unpleasantness won’t be mine,” The accused said viciously, “but the thief’s.”

“This brooch has been taken from your house, you saw?” the lawyer questioned her. All the passengers within hearing were listening with intense curiosity, George among the rest. This would be a grand yarn to spin for Elsie’s amusement when he presented her with the moonstone brooch.

“I didn’t know that it was stolen,” said the woman, “till I saw it just now. But I’ll find it gone when I get home. And he’s coming with me to the police station, and there’ll be a policeman there when I open the jewel box.”

The lawyer was shocked.

“And you accuse a stranger on as slight grounds as that?” he reproached her.

“I’d know that brooch anywhere,” she said sullenly, “No mistaking it.”

“But, even so, there are a hundred possibilities of it having been stolen by someone else, sold, and bought by its present owner, as he avers.”

George Hoare broke into the discussion.

“It’s all right,” he said easily. “I’ll go home with you, madam, and wait while you find your brooch.”

“Then we get out here,” she said. They were slowing down for Golder’s Green station.

The last sight the other passengers had of the two were striding together towards the exit, the woman holding George firmly by his shabby sleeve.

In complete silence they strode along the street, George struggling with a growing desire to shout with laughter. Here was a very pretty little adventure that exactly suited his humour. Glancing at his accuser’s face, he was struck by the vindictive set of her thin mouth. He was sobered by a sudden idea. If t turned out that the brooch really was the property of this spiteful woman, and the real thief was within her reach, heaven help the wretch, thought George Hoare.

They had not far to go. Opening the gate of a semi-detached villa, and locking her arm through her victim’s, the woman produced a key and opened the front door.

“Mary!” she called imperiously. A door opened on the right, and a girl stood in the doorway.

“Yes, aunt?” she said.

In a moment George Hoare was alert. The girl in the doorway had a sweet little sensitive face, deep blue eyes, wide now with unmistakeable fear.

“This man,” said her aunt, in her harsh, grating voice, “has stolen some of my jewellery. Stay with him in the sitting room till I go up and see my jewel-box.”

George followed the girl into the sitting room. As the door was locked upon them she turned to him and asked breathlessly—

“What is it?”

George held out the moonstone brooch.

The girl’s face went white. She gave a low cry of fear. “Oh!” she said, in a voice of agony. “You didn’t steal that, I—I took it and sold it.”

“You” said George with conviction, “are no thief.”

“No,” she said. They stood close together and spoke in urgent whispers—the dread woman might return at any moment. “It was my mother’s—that and a little more. She’s dead—my father, too. Aunt Maria keeps everything—says it’s hers because she’s spent more than that on my keep. She broke my violin.” The girl’s voice was broken into sobs. “I had to have it mended—no money, so—”

The key turned in the lock, the door was flung open. “The brooch is gone!” shouted Miss Grainger. “Put on your hat at once, Mary, and go for the police while I hold the man here.”

The girl’s eyes were agonised.

“I can’t,” she said, and shivered at the look cast on her.

Had it not been for the girl, George Hoare reflected, the situation would have amused him well. It would have been great sport to see the routing of this terrible woman. The dealer would have no difficult in identifying the brooch and the purchaser. But neither would he have the least difficulty, at the same time, in describing the person who had brought the jewel to him.

The appealing blue eyes, the strained white face were raised to his. One glance at the uncompromising jaw of his accuser and George’s resolution was taken. If the police arrived he must act the thief to save this trembling girl. It was a nasty situation.

He met the girl’s eyes. She moved nearer to him.

“You have the brooch restored to you,” George said as he laid it down on the table. “Will that satisfy you?”

Miss Grainger took not the least notice of him.

“Go as I tell you,” she commanded the girl sharply.

George nodded to her to obey. With reluctant steps the frightened girl went her way.

As the door closed he turned towards Miss Grainger, shrugged his shoulders, pointed to the moonstone brooch. “This pleasant interview may end now, I think,” he said and moved towards the door. With a swift stride that her put her powerful shoulders against it, eyeing him maliciously.

“So you think that ends it, you young thief! You’ll soon find out the sort of person you are up against. There you stay until the police arrive—”

She never could understand how it happened, but in a moment the room was plunged in darkness, and when the lights went on again the window was open and the man had completely disappeared.

Running, as he left the gate, George nearly ran down a girl who stood rooted on the pavement under a lamp.

“What—you!” He stopped and gazed into the trouble blue eyes. “Why haven’t you gone for the police?”

She wrung her hands.

“I couldn’t. I was trying to get courage to go back and tell her it was I.”

“That was a brave offer,” said George admiringly.

“No, no—of course I couldn’t have let you be accused. If the police had come I’d have had to confess before them.” The girl was distraught with fear. “And be taken for a thief.”

They were walking rapidly down the road as they talked.

“But the brooch is yours,” said George.

“How could I prove it?” Mary Grainger asked him. “Only my word against hers. Oh, you don’t know what she is like.”

George thought that he had more than an inkling. His face grew stern. To think of a sensitive child in the power of a woman like that made him feel murderous.

“Have no more fear,” he smoothed her. “I practically confessed to the theft. You are out of it. Get the police for her, or there’ll be trouble over the omission.”

“Oh, how good you are—how wonderfully good.” The eyes raised to her rescuer were so warm and sweet that George’s heart beat faster. “But it’s not safe for you. How can I?”

“No man better able to look after himself than I,” Hoare assured her in light tones. “This neighbourhood, I grant you, may not be a healthy one for me for some time to come. I might wear a fake beard and tortoiseshell spectacles, of course—”

“How can I thank you?” asked Mary Grainger softly. “You do everything for me and get nothing out of all the trouble for yourself.”

“I get the moonstone brooch, of course,” George answered. “And it has quite a particular value for me.”

The girl’s eyes were white.

“I thought you gave it back to Aunt Maria?”

“And took it again, along with my unceremonious leave. I bought it for a girl who is hard to give presents to, she has so much already.”

Mary fell silent, considering this happy girl who had so much, and the love of a hero like this besides.

The police station was within sight. They paused abruptly.

“I must know how you get on,” he said.

“You must promise never to come near here. Promise me.” Her eyes were dark with anxiety.

“Done, if you promise to meet me somewhere else,” George said. “What about lunch together in town tomorrow? I’d meet you outside the Piccadilly tube station at half past one o clock.”

“I’ll try—I’ll try,” Mary assured him eagerly.

“The crook vanished from her sight with long, stealthy footsteps,” said Hoare, in a stage whisper, “carrying his plunder with him. The lights from the police station glared for a moment upon him before the darkness swallowed him up. The girl ran like a hare to give the villain in charge. Alas!—too late!”

He lifted his hat, waved it gaily, and was gone from her sight.

He waited on the pavement beside the Piccadilly tube next day, and the moments dragged, each more intolerably. Hundreds of people seemed to pour out incessantly, but never the one he looked for. His anxiety grew.

The small, wistful face had haunted him all night. Nothing had ever put him off sleep before. What was he to do if she did not come? She had no address of his—he cursed his folly. He could not writer to her, for he was convinced that the dreaded aunt would think nothing of opening letters. Perhaps she was suffering acutely even now. What was he to do? Should he send Elsie to call on some pretext or other?

She would not come now, he fretted, an hour gone, but still he lingered. Suddenly Hoare’s frowning face changed. She was coming towards him, her white face rose-colour, her blue eyes alight. His relief was so great that he held her small hand in a crushing grip, forgot to let it go.

“I’m so sorry!” gasped Mary. “I couldn’t help it. Oh, I’m so glad to find you. I thought you’d have gone, it’s so late.”

“Time,” said George Hoare pleasantly, “is nothing, but my hunger is great.” He hurried her along.

In a few minutes they were seated in an almost deserted upstairs room, where Hoare was apparently well known. Succulent food appeared at once.

The flush had fled out of Mary’s face. Hoare suddenly saw its pallor. The dark blue marks under her eyes.

“You’ve had a bad time?”

The girl nodded.

“Aunt Maria was so upset at your escape and the second loss of the brooch. She told the police that you belong to a gang of crooks, that your escape was assisted.”

George smiled delightfully. “That was very like a finished crook, wasn’t it, to offer to go home with her? Why, the slightest wrench of her arm and I could have escaped any moment.”

“She’s very strong,” said the girl gravely. “She prides herself she’s stronger than most men.”

Hoare saw the shrinking girl along with the strong woman, dominating her grim childhood.

“How old are you?” he asked abruptly.

“Eighteen,” she told him.

“Leave the woman,” he advised. “Go on your own.”

“I am trying,” she said eagerly. “If I only could get violin pupils. I would have to be in their own houses, but I don’t know how to go about it.”

Hoare’s eyes were full of thought.

“Well,” he said, “I think I could secure you one for a beginning.”

She thanked him fervently.

“You would have to teach him from the beginning,” he said. “He doesn’t know his notes, but he has a passion—I might call it the beginning of a consuming passion—to be taught.”

“A musical little boy.” Mary’s face grew rosy again, her eyes bright. “How ‘d love that more than anything! Are you sure, quite sure, you could get him for me?”

“Nothing surer,” Hoare returned. “But he isn’t a very little boy. Indeed, he is thirty years old, one month and six days. His is a sad case. His musical education, poor child, has been entirely neglected.”

She looked inquiringly at him. The colour died out of her face.

“I see,” she said slowly. “You are very generous, but I have taken far too much from you already.”

“It is not generosity,” he assured her. “You see, the girl I mean to marry is musical. She would like me to know enough to appreciate her playing. I should like it myself.”

“If that is the case”—Mary’s voice was small and quiet—“I’ll only be too glad to teach you what I can.”

“Come with me now, can you, and buy a violin?” he asked. They went out together.

“You try them over,” he told her, as they entered the shop, “and choose the one you like best for me.”

The music seller, overhearing, beamed.

This was the class of customer he spent his days hoping for—the best required, the price immaterial.

In an inner room he handed out a violin. Mary took it with an exclamation of joy, drew the bow lightly across it. Her eyes were full of beaming joy.

“You like that one?” said Hoare. “Then I’ll have it.”

“It’s a lovely one,” she said reverently. “Will you show us some moderately-priced ones for a beginner?”

As the shopman departed, crestfallen, Hoare turned to his companion.

“I’ve decided that I’d learn much more about music,” he said, “if you played to me several times a week and explained all about it than if I scraped a bow up and down the strings. I honestly don’t think Elsie would stand much of that from me.”

So Elsie was the name of the girl he loved—the girl who was hard to please because she had so much.

The shopman returned with a cheap new violin in his hand, proffering it to Mary to try.

“I prefer the tone of the other,” said Hoare.

“Well, naturally.” The shopkeeper could not forbear to smile. “The one is six pounds and the other five hundred pounds.”

“Pack it up and send it, then,” said Hoare.

“Which, sir?”

“The decent one, of course.” He began to hunt through the pockets of his shabby suit. “I’m always forgetting to bring money,” he said to Mary. “That day I saw the moonstone brooch I’d spent it all. Ah, here’s a cheque-book. Good.”

It was a month later that George Hoare, seated beside the fire in a comfortably-furnished library, brought the moonstone brooch out of his pocket.

“What a charming little brooch!” The girl on the opposite side of the fireplace laid down the book she was reading.

“Yes. I bought it for you, Elsie, for your last birthday.”

“And forgot all about it?” his sister said. “How like you—hand it over.”

George Hoare’s large hand closed over the moonstone brooch. His eyes were gleaming.

“Its destination has changed,” he said. “It is to be my first present to my wife.”

Read and listen to our previous Reading Between The Lines stories.