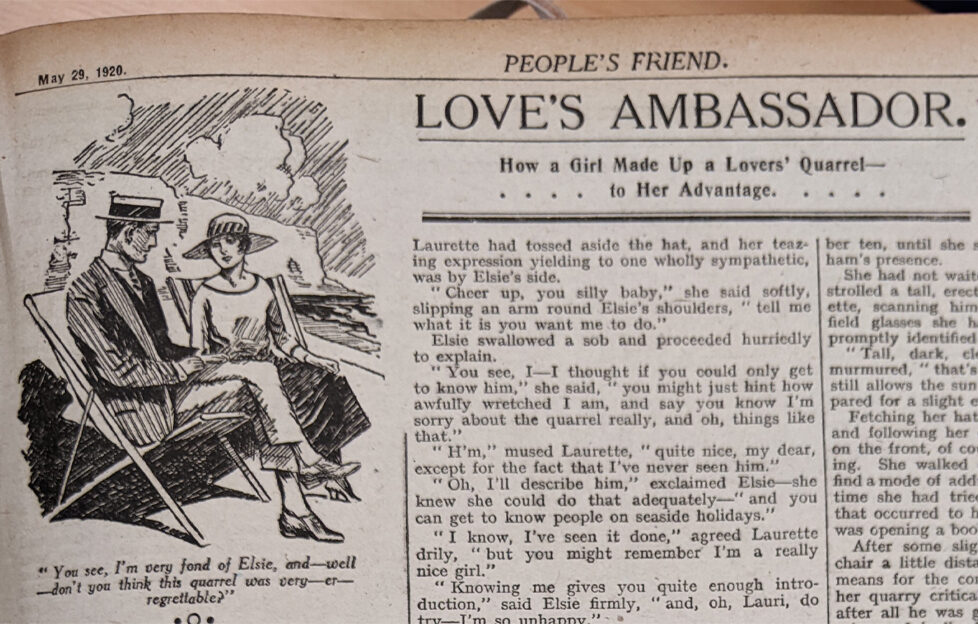

The next episode of the Reading Between The Lines podcast is “Love’s Ambassador” by Ida May, first published in May, 1920. In this episode, Jacqueline falls a little bit in love with our love interest! And the episode gets derailed slightly by David’s wild “Friend” Editor, David Paye, conspiracy theory . . . Listen along to the episode as you read and let us know what you think!

Laurette Wayne pulled the ends of ribbon into fringe, fixed it on the brim of the hat she was trimming, and then fixed her expressive eyes on the girl who sat fidgeting with the skein of cotton opposite.

“What did you come to see me for, Elsie?” she asked.

Elsie Foster, her friend and office companion, flushed. “How did you know I came to see you about anything particular?” she asked.

“Well, my dear, when a friend calls, ostensibly to wish me a pleasant holiday, and after muttering a few vague remarks about the weather, sits there saying nothing and getting my cotton into a mess, I begin to wonder.”

Elsie sat down the cotton hastily.

“Dick’s going to Margate today,” she said abruptly.

“Ah – h!” murmured Laurette, beginning to stitch.

“Edna Spence told me, Dick told her brother; he’s staying on the same street as you are.”

Laurette stitched on in silence; when its subject was Dick Woodham, Elsie could safely be left to continue her conversation alone.

“I — I, oh, I do wish we hadn’t quarrelled!” Elsie burst out.

“Why don’t you write and tell him so?” Laurette asked placidly.

Elsie sniffed. “It was all his fault,” she said, “how could anyone be so unreasonable?”

“Let’s see, you quarrelled about going to dances, didn’t you?” Laurette asked; she knew, all the office knew, why Elsie and her sweetheart had quarrelled, but she wanted to get the hat finished while Elsie talked.

“He was so — so old-fashioned,” wailed Elsie, the ready tears rising to her brown eyes, her pretty childish mouth taking on a wistful pucker, “you know how I love dancing, and he said that after we were married, of course, he wouldn’t expect me to go anywhere without him, and he doesn’t dance; he said a wife’s place was in her home and — and a lot of stuffy things like that. And I told him I should expect to go out when I liked and — and —”

“And you ended up by having a really first rate row,” said Laurette cheerfully.

“And we’ve not made it up yet,” agreed Elsie, with an extra loud sniff.

Laurette rose and, going to the mirror, placed the hat on the shining waves of her chestnut hair.

“Does it suit me?” she asked, crinkling her pretty tip-tilted nose in an endeavour to make sure.

“Yes, they always do,” sighed Elsie vaguely. “I wish you’d fall in love Lauri, then you’d understand.”

“Thank you,” answered Laurette with the fine scorn of the entirely heart whole, “my friend’s love affairs give me quite enough diversion at present.”

A sudden tear dropped on the skein of cotton Elsie was still playing with and in an instant, Laurette had tossed aside the hat and, her teasing expression yielding to one wholly sympathetic, was by Elsie’s side.

“Cheer up, you silly baby,” she said softly, slipping an arm around Elsie’s shoulders, “tell me what it is you want me to do.”

Elsie swallowed a sob and proceeded hurriedly to explain.

“You see, I — I thought that if you could only get to know him,” she said, “you might just hint how awfully wretched I am, and say, you know, I’m sorry about the quarrel really, and oh, things like that.”

“Hmm,” mused Laurette, “quite nice, my dear, except for the fact that I’ve never seen him.”

“Oh, I’ll describe him,” exclaimed Elsie — she knew she could do that adequately “— and you can get to know people on seaside holidays.”

“I know, I’ve seen it done,” agreed Laurette drily, “but you might remember I’m a really nice girl.”

“Knowing me gives you quite enough introduction,” said Elsie firmly, “and, oh, Lauri, do try. I’m so unhappy.”

Laurette crinkled her nose, a habit usual to her when she was dubious over anything. The coming weeks held her one holiday of the year and, for their all too brief days she wanted to lie on the sun-warmed sands and look over the blue waters, to wander on the poppy blazoned cliffs and forget that there were such things as offices with typewriters that clicked and ledgers that rustled; she wanted to do many things, but making up Elsie’s quarrel with Dick Woodham was not one of them; yet, essentially kind-hearted, how was she to refuse? Poor Elsie, she was really sorry for her; she had been deeply attached to her sweetheart, their wedding day had been already on the point of being settled; and she shrewdly suspected that Dick, who, she had heard from several sources, was wholeheartedly in love with Elsie, and was as unhappy as the girl herself; each, after the usual manner of quarrelling lovers was waiting for the other to give way first.

“Why don’t you write to him, Elsie?” she asked gently, “that would be much the easiest way.”

“My pride won’t let me.” Elsie sniffed, “besides, it was his fault.”

“Oh, well,” said Laurette with more cheerfulness than she was feeling, “I’ll see what I can do. I’ll waylay him in my best hat, and a special smile I practise before the glass, and I daresay I shall bring the young man to reason; now give me a full description of him and his address at Margate.”

Nothing loth, Elsie launched forth into descriptions so flattering that Laurette decided addresses and all details were superfluous, there could only be one man as handsome as that in any town.

“And,” wound up Elsie, “Peggy Mason is down there, too, and I know she’s in love with him.”

“I don’t wonder,” murmured Laurette. “If he’s all you say, she couldn’t help it.”

Elsie wrote down the address. “It won’t be a boarding house because he doesn’t like them, so you can’t make any mistake,” she said, “but be sure and don’t let him guess I told you to do it; you can say someone pointed him out to you,” and then, after many more instructions and entreaties, she went.

On the morrow, Laurette arrived at her destination with the holiday spirit waxing strong within her. The skies were clear, the sun shone, there was the sea, the glorious sea, blue and flecked with fairy foam.

Laurette nearly danced from the station to the boarding house; there was a merry company assembled there, mostly young people intent on making the most of their holiday, and for the next day or two Laurette enjoyed herself to the full, but her promise to Elsie weighed heavily upon her, and on the fourth day she took up her stand on the little balcony from which all other houses in the street could be seen, and determined to keep watch on number ten — yes —she consulted the address Elsie had given her again, it was number ten, until she should be sure of Dick Woodham’s presence.

She had not waited long when, from number ten, strolled a tall, erect, flannel-clad figure and Laurette, scanning him eagerly through the pair of field glasses she had borrowed for the purpose, promptly identified him.

“Tall, dark, clean shaven, um-um-um,” she murmured, “that’s the lad, of course; his beauty still allows the sun to shine, but I was not unprepared for a slight exaggeration on Elsie’s part.”

Fetching her hat, she was soon out in the street and following her quarry; he was going to stroll on the front, of course — everyone did in the morning. She walked on, Dick well ahead, trying to find a mode of address and failing utterly. By the time she had tried and rejected all the openings that occurred to her, Dick had seated himself and was opening a book he carried.

After some slight hesitation, Laurette found a chair a little distance away and, still seeking the means for the conversation she intended, studied her quarry critically. Yes, she decided suddenly, after all he was good looking; his dark hair was crisp and inclined to curl, his features clear cut, his mouth firm and pleasant; suddenly he looked up and their eyes met.

Laurette tried to grasp the opportunity and failed utterly, while the man, after a fleeting moment, looked back on the printed page, but his attention seemed to wander, and more than once he found himself studying the girl in the green gown, watching the sun playing in her hair, looking at the pretty mouth and feeling sure there was a dimple when she smiled. Somehow she made the heroine of his book seem dull and he felt dull with her.

Presently Laurette, deriding her own shyness, rose to go; it was no use this morning, she knew, “But I will tomorrow,” she vowed fiercely. “I will, whatever I feel like,” and then she was conscious Dick had risen, too, shutting his book with a bored yawn, and was following her up the parade.

But she did not address him the next day, nor the next, nor even the day after that, despite her resolution. Holidaymakers do the same things and go to the same places, and she passed him a dozen times and with each passing she was uneasily conscious that his glance grew more admiring and his interest more apparent. “Wonders what I stare at him for, of course,” she told herself angrily.

It had seemed so simple when she had given Elsie that promise, and she had intended to approach him with an elder sister young-man-you’re-behaving-foolishly kind of attitude, and now, looking at those blue eyes with the twinkle in their depths, that firm mouth curling so pleasantly at the corners, she found it in her heart to wish Elsie and her love affairs elsewhere.

On the fourth day, goaded by an imploring epistle from Elsie, she took the plunge. Strolling along the front at an hour too early for the usual crowd of promenaders, she saw Dick in a deck chair; he was without the usual book and, passing, their eyes met; for a moment Laurette halted, then she gathered her courage tight in both hands, and dropped quickly into the chair next to him.

“Mr Woodham, I’m a friend of Elsie Foster,” she began breathlessly, and then stopped short; how silly it sounded, how unlike the careful speech she had planned!

He turned to her and for a moment he hesitated, surprise and something not so easily read in his smile, then he raised his hat, and seeing his smile, somehow Laurette grew more at ease; you could, she felt, explain things to a man who could smile so understandingly.

“You must forgive my interference,” she said, her own eyes beginning to twinkle in company with his, “but you see, I’m very fond of Elsie and — and — well, don’t you think this quarrel was very – er – regrettable?”

“Nearly all quarrels are,” he agreed gravely.

“It seemed such a foolish thing to part two people who were — and, I expect, are so fond of one another,” she went on.

He looked out over the waters and sighed, and Laurette, hearing that sigh, grew hopeful, and some of the young-man-you’re-behaving-foolishly speeches came flowing back to her.

“Did Elsie tell you about the quarrel,” he asked?

“Yes, she can’t think of anything else just now; I believe you think once a girl is married she ought to stay in her home and not go anywhere, nor have any amusements you didn’t share?”

“Those are my ideas,” he said firmly.

“But don’t you think a girl would get dull if she gave up all her amusements just because she was married; and the man wouldn’t like a dull wife, would he?”

“No-o,” mused her companion, but I should sort of hope my company would keep her from it.”

“There must be endless give and take in matrimony,” argued Laurette with the bland inexperience of those who have never tried it, “but, anyhow, I know Elsie is very lonely.”

“So am I,” he said.

At this admission Laurette felt comfortable glow of the well-doer; she was going to succeed in her mission, the rest was easy. She went on to talk of Elsie, but her companion revealed to her that he had views of his own and knew how to express them in a manner both interesting and forcible.

One argument led to another, and they were still talking when the chime of a church clock told Laurette the lunch hour was upon her. With a gesture of dismay, she sprang to her feet.

“I had no idea it was so late,” she exclaimed, “but you do understand why I spoke up, don’t you? And I can hope that you and Elsie will make it up?”

He rubbed his chin meditatively. “I must say you give me new points of view,” he admitted, “but I’m an obstinate fellow, and I don’t know yet that Elsie was altogether right. I should think it very kind of you if you would walk out to Westgate this afternoon with me and tell me more of her ideas; you may put them more impartially than she would.”

Laurette hesitated, but not for long; hadn’t she promised Elsie to do her best? And she believed in seeing things through.

“Very well,” she said, “I’ll come; I’d do anything for Elsie.”

He frowned, then laughed suddenly. “Thanks,” he said. “I’ll try not to make my company too severe a test of your friendship.”

They walked to Westgate beside the cliffs, and though Laurette started to explain more of Elsie’s views, her companion lured her skilfully off the topic and on to others he seemed to find more interesting, and when at length they parted at an hour considerably past the one Laurette had contemplated she was left with the uneasy conviction that as a special pleader she had not been altogether a success.

She crinkled up her nose in puzzled thought; how was it she had come to talk of so many other things besides Elsie, who, she decided suddenly, was a little fool to quarrel with a man like that.

Then she checked herself sharply, colouring all over her small, vivid face; what did it matter to her what kind of a man he was? She was Elsie’s friend, not his. Almost she regretted she had promised to go for a row with him tomorrow; still, she told herself that would be the last time; tomorrow he would talk of nothing but Elsie, and then, well, she’d done her best; if they didn’t make it up it was not her fault.

Out on the sunny water, she did her best to keep to her resolution, and talked only of Elsie and the amazing luck of the man who could make her his wife, but her companion showed so little interest in the subject that presently she lapsed into silence and lay back in a boat and watched Dick sending it through the water with long, easy strokes. Elsie was a little fool!

“Are you doing anything this afternoon?” he asked as he handed her out of the boat, holding her hand rather longer than was at all necessary.

For a moment she hesitated, but only for a moment; disloyalty was not in her nature.

“Yes,” she said firmly, “I’m afraid I’m booked pretty well all the rest of my holiday; thanks so much for the sail; you will make it up with Elsie, won’t you?”

He looked long at her. “Yes,” he said at last. “I’ll make it up if she wants me to.”

Then she had healed breach, Laurette told herself as she went indoors; she was delighted, she told herself so many times in order that she might be quite convinced. He would write to Elsie at once; perhaps he might even go up to see her that very day; she probably wouldn’t see him again.

But here she was wrong, for she saw him the very next morning when he waylaid her as she was going down to the front. Elsie had been written to, he assured her, and wouldn’t she walk out to Kingsgate with him? And secure in the knowledge of the letter to Elsie, Laurette went.

The next day and the next, and the one after that she spent in the same company, spent them, too, in a happiness hitherto unknown, a happiness she did not dare to define; and still Elsie did not write her the joyful letter of gratitude she fully expected. Odd, she thought, very odd, for in answer to her questionings Dick assured her that Elsie was aware of his unchanged feelings towards her, and Laurette, whose instinct in such matters was unusually sure, believed him and did not make the determined efforts to avoid him she would otherwise have done.

After a week, a week spent almost entirely in the company of her friend’s sweetheart, Laurette rose very early one morning and stole out of the house and up on to the deserted cliffs, cool and sweet in the keen air, from which the opaline mists were clearing before the coming sun, and here, seated on an upturned boulder, she faced the situation.

“You’re not playing fair,” she told herself, clutching her slim hands — tanned pale gold with the sun and sea winds — “and you know it.” There was only one thing for her now, she thought, since she could not be with Elsie’s sweetheart and remain loyal to her friend in thought as well as word; there was nothing left for her but flight, and that at once.

Why, oh, why had she consented to meddle in Elsie’s love affair, Elsie’s that had nearly so become her own! She sat long, looking seaward and bracing herself for renunciation, and when at last she rose and went down towards the town it was with the firm resolution to catch that 2.20 train the same day. It meant losing a week of her holiday, but anything, anything was better than disloyalty to Elsie.

It was long past her usual time for appearing when she reached the boarding house only to find Dick Woodham waiting at the entrance.

“Good morning,” she said, and would have passed him, but he blocked her way.

“I’ve been waiting such a long time for you,” he said reproachfully, “you didn’t tell me you were going out so early.”

“I am sorry you waited,” she answered in a voice she strove to render expressionless and cold. “Something has happened that makes it necessary for me to go back to town today.”

He looked straight at her, a long, intent look that Laurette forced herself to meet without flinching. He must never guess, never, she would rather die!

“What train are you catching?” he asked suddenly.

“Ah,” he said when she told him, “what a pity; Elsie is coming down today by the 3.15; I heard this morning, and I did hope you would come with me to meet her; couldn’t you possibly stay till tomorrow?”

Laurette caught her breath sharply. So Elsie was coming down. She needn’t go, she told herself, with a bitter little smile; it was all quite safe, Elsie was coming down to her fiancé today.

“Do stay,” he urged. “I counted on you coming to meet her after all you’ve done for — us.”

Laurette came to a swift decision. She had better stay lest even a dim suspicion of her reason for going should come to him. Just now there had been a look in his eyes that sent the blood rushing to her heart.

“Oh, yes,” she said gaily, “I must certainly stay and congratulate you on your reunion.”

“That’s right, he said, “I’ll call for you this afternoon then?”

She nodded and left him, humming a gay little tune as she entered the house.

They set out in good time to meet the train, Laurette laughing and talking in a gayer mood than her companion had seen her. Only to herself did it seem that the way to the station was paved with thorns; the sun hidden; the very brilliance of the sea, the gay crowds on the beach, a mockery. She must go tonight, she told herself; whatever anyone might think, she must go tonight.

The station was reached at last, and as the train came in Laurette braced herself for the final effort. She must watch the meeting with a gratified smile and speak the words she knew would be expected of her.

“There they are,” Dick said quickly, and even as he spoke she saw Elsie coming towards her, a tall, dark man at her side.

“Why, who—?” she was beginning when Elsie saw her and rushed up, greeting her warmly.

“Oh, Lauri,” she cried. “How can I ever thank you? I know it was all your doing, though I don’t know yet how you managed it, and — and this is Dick,” she concluded, pulling her companion forward. “Dick,” she said, “this is Laurette, who helped us to make it up.”

The dark young man put out his hand and taking the one the bewildered Laurette extended, pressed it warmly.

“It was awfully good of you to bother,” he said. “Alec has told me all about you.” Here he turned to Laurette’s escort and smote him on the back. “Hullo, old chap,” he added, “you see, you’re going to be my best man after all.”

The other laughed and pushed him gently forward. “Go on,” he said. “You and Miss Foster can walk up alone, we would not spoil sport for the world, would we Miss Wayne?”

And before the astonished Laurette could reply, he had taken her arm, and was piloting her out of the station and on to a quiet seat on the front.

“Who are you?” she demanded when she could find words.

“Alec Trevor, Dick Woodham’s chum,” he answered.

“Why didn’t you tell me you weren’t Dick Woodham?” she demanded.

“You never asked me,” he smiled.

She tried to frown, and he explained. “You see,” he said, “if I had told you at first you wouldn’t have gone on talking to me and I wanted to know you more than I’ve ever wanted anything; I noticed you the very first day you came and — and after — well, I just waited until Dick could come down and you could see him.”

“But why wasn’t it him?” Laurette asked vaguely.

“We changed holidays at the last minute; he had arranged his rooms and all, and then when he quarrelled with Elsie he felt too hipped to come, so I came instead. Are you really sorry I did?” he asked softly.

“You said Elsie had been written to,” she answered, looking away.

“So she had,” he told her. “Every night after I left you, I used to sit down and write all your arguments to Dick, pointing out to him all you’d pointed out to me, and you see it worked, for between us we healed the breach. You talked to Dick by proxy; you were a loyal friend, but oh how sick I did get on the virtues of Elsie; I never thought so perfect a person existed; no man would be good enough for her.”

There was a long silence. Laurette looked out over a sea grown suddenly radiant; the sun overhead seemed to shine down into her very heart, warming it to life again.

“Don’t you think you could possibly forgive me?” he asked at length.

“I’ll try,” she murmured.

Under cover of the paper he carried his hand reached out and sought hers. “But,” he whispered, “I promise I’ll let my wife go to dances without me if she wants to.”

Laurette shot him a lightning glance.

“I don’t think she’d want to,” she whispered.

And truly enough she didn’t.

Read previous stories and updates from the podcast.