Our first episode of season 3 of Reading Between The Lines is “Changing Heart” by Margaret Scott, first published on July 21, 1945. You can read along with the story (written as it first appeared) as you listen to the episode and what the team had to say about it.

Sarah Ramsay had two interests in her life, one was the bleak, north-country farm to which she had come as a bride nearly thirty years ago and the other was her son Ian.

Widowed five years after her marriage when Ian was still a baby, she poured all her energies into scraping a living from the unwilling soil of Greenlaw and all the love of her proud, reserved heart on her son, although an onlooker might have found few outward traces of affection, because Sarah—like Greenlaw—had a bleak exterior. But Ian understood his mother—he never expected caresses nor soft words. Sarah Ramsay wasn’t that kind.

There was nothing bleak about Ian, with his frank face and his russet hair sweeping upwards from a wide brow. Ian was clever, so Sarah scrimped and saved in the difficult years before the war to give him his chance. There was no thought of leaving school at fourteen to start work on the farm for Ian. He took the Leaving Certificate at sixteen, went on to the university and graduated with honours at twenty-one; at twenty-two he was in the army, and at twenty-three, Captain Ian Ramsay was married in England to Nina Rosemary Williams—whom Sarah had never seen.

His letters were full of Nina; happiness spilling across every page. Nina was wonderful. He’d never met anybody like her before. Everybody loved Nina, so that proved he wasn’t just prejudiced in the matter! He knew his mother would think they were too young, but times and values had changed. There was no time to wait for anything. Time was too precious to be used up in waiting.

Nina had never had a real home of her own. Her parents had died when she was a baby. She was crazy to come north to Greenlaw with him, and he hoped to wrangle a leave pretty soon. “So kill the fatted calf, Mother—”

Of course Sarah had disapproved. Ian was far too young, and the young had no sense when it came to picking themselves wives. But she’d had to accept it now it was done. Sarah never believed in crying over spilt milk.

But Ian never did bring his bride to Greenlaw. Instead, Sarah left the farm for long enough to make the awkward journey to Aberdeen to meet the south train, and bring back a white-faced, grief-stricken young girl, with her—alone.

Sarah had never shed a tear that anybody saw, but she forgot her habitual reserve of manner for long enough to hold the sobbing girl gently in her arms during those difficult first days until the shock died away and Nina settled down at Greenlaw, still white-faced, but composed. Then Sarah retreated within her shell again, and Ian’s name was seldom mentioned between them, although he was never far from Sarah’s thoughts—and they were bitter thoughts. It seemed as if the mainspring of her life was broken. Ian had been everything to her. She had been so proud of him.

She respected Nina’s grief and made her welcome at Greenlaw because she was Ian’s wife—but what was Nina’s loss compared with her own? Nina had known him only a few short months, but he was her son, her bairn that she had watched grow from dependant childhood to vigorous manhood, loving him every moment of it.

She and Nina were united by their common grief, but if Sarah became fond of the girl, she never was aware of it. She had no room in her heart for anything but the memory of Ian, and Nina was not part of that memory. The girl merely fitted into the life of Greenlaw so that the visit lengthened until there was no longer any talk of her going away. She was too fragile for heavy work, but she was useful in the house and eager to learn. Soon Sarah was glad to hand over the running of the house and all the clerical work in connection with the farm, which had been such a burden to her.

They led a very quiet life. Twice a week one or both of them went by car to the village for messages; every Sunday saw them in the family pew in the Parish Church, but they were too far from the village to take much to do with its social life—if they had wanted to.

One year slipped into two; Sarah’s joints were a bit stiffer, and Nina could now bake on the heavy girdle that hung onto the sweep above the open fireplace. The oil-heated oven held no terrors for her now.

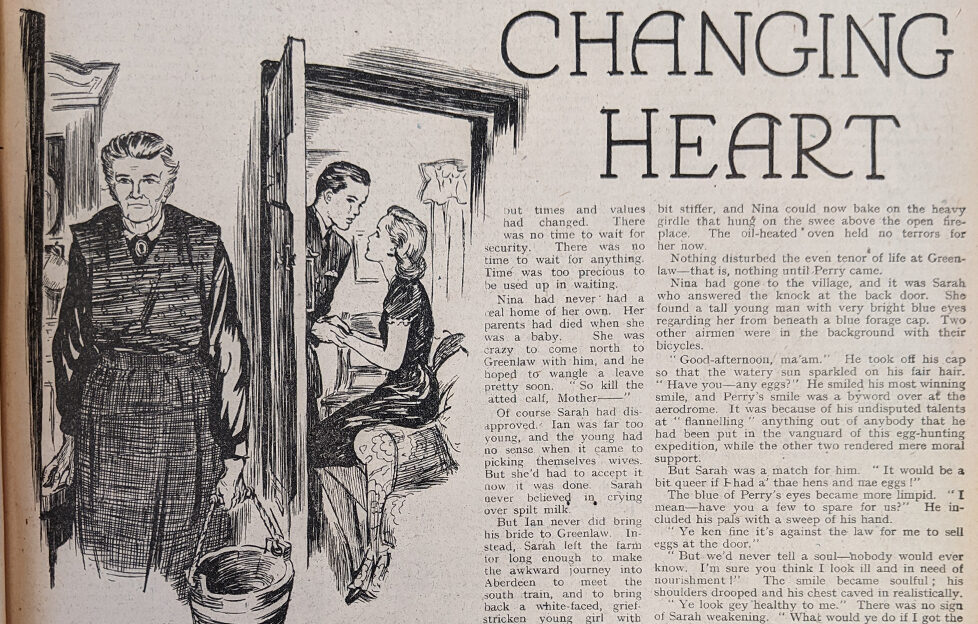

Nothing disturbed the even tenor of life at Greenlaw—that is, nothing until Perry came.

Nina had gone to the village, and it was Sarah who answered the knock at the back door. She found a tall young man with very bright blue eyes regarding her from beneath a blue forage cap. Two other airmen were in the background with their bicycles.

“Good afternoon, ma’am.” He took off his cap so that the watery sun sparkled on his fair hair. “Have you—any eggs?” He smiled his most winning smile, and Perry’s smile was a byword over at the aerodrome. It was because of his undisputed talents at “flannelling” anything out of anybody that he had been put in the vanguard of this egg-hunting expedition, while the other two rendered mere moral support. But Sarah was a match for him. “It would be a bit queer if I had a’ thae hens and nae eggs!”

The blue of Perry’s eyes became more limpid. “I mean—have you a few to spare for us?” He included his pals with a sweep of his hand.

“Ye ken fine it’s against the law for me to sell eggs at the door.”

“But we’d never tell a soul—nobody would ever know. I’m sure you think I look ill and in need of nourishment!” The smile became soulful; his shoulders drooped and his chest caved in realistically.

“Ye look gey healthy to me.” There was no sign of Sarah weakening. “What would ye do if I got the jail?”

“I’d come and see you,” he countered gleefully at once.

A gleam of something that might have been a smile chased itself across Sarah’s grim face. Her hand itched to warm the ears of this impudent loon, but instead she stepped back. There were few folk whose tongues could get the better of Sarah Ramsay.

“Come in, but wipe your feet and no’ foul my clean floor.”

He came in, and so did his companions, so that the kitchen seemed to be overflowing with sergeants in blue-battle-dress. They were quiet and stood around self-consciously, that is, two of them did. Perry was never quiet under any circumstances. He sat on the edge of the table, and conversation came tripping off his tongue as easily as rain flowing off a roof.

Nina drove into the yard as they were leaving, her fair hair escaping at the front of her blue knitted hood. All three of them came off their cycles again and helped to carry the messages into the house. Then they went—reluctantly—and Sarah breathed a sigh of relief.

“Who were they?” asked Nina without much interest, crouching down at the fire to heat her chilled fingers. She’d never become really used to the biting winds that swept in from the sea.

“They were wanting eggs.” Already Sarah was regretting her momentary weakness. She was afraid they would be back. The farms close by the aerodrome had no peace at all. Aye, they would be back—and the aggravating thing about it was that she had nobody to blame but herself.

She was right. The three airmen came back—and came in. You might as well have tried to hold back the sea as keep them at a distance. Nina was on her knees on the stone floor, surrounded by eggs and crates, and in no time she had two helpers who packed the eggs—breaking only one—nailing down the lids and addressed the labels, all in double quick time.

While this was going on, Perry talked to Sarah. The fact that he had got little encouragement did not deter him, and in the end her resolution weakened, and she gave in.

She never knew quite why she did it. Perhaps it was because she noticed that the brown-haired one—the one they called David—wore a scrap of ribbon beneath his wings, or perhaps it was because there was something in Perry’s light laughter that reminded her, suddenly and painfully, of a deeper and more resonant laugh that used to ring out in the past. Anyway, it happened.

“Would ye care for a drink of milk?” It was said grudgingly, but it was said.

They would, so Sarah went herself into the chilly milk-house to ladle the thick, creamy milk into tumblers. Scones, pancakes, butter and jam went on the table and vanished like snow in summer. What appetites loons had, to be sure.

Sarah remembered Ian, and the inroads he used to make on her pancakes, and in spite of herself her heart softened towards these English lads with their easy laughter and their unfamiliar ways.

After that, they just kept on coming, sometimes the three of them, sometimes one or two, till she almost ceased to think of them as strangers. In time, she came to know them as well—better—than she knew her nearest neighbours, and to accept their frequent appearance at Greenlaw as part of ordinary life.

David was deceptively quiet, with a sudden wit that flashed out unexpectedly. He was the only one capable of putting Perry—temporarily, anyway—in his place. Johnnie was the dark, stockily-built one who was painfully shy at first, and very boyish in his manner. It came as a distinct shock to Sarah when she knew he was married. His wife was staying near London—Pat, her name was—and he was very much in love. He showed Sarah innumerable photographs of a girl with an untidy mop of hair as dark as his own, and a wide, engaging smile. Then there was Perry, always bubbling over with some kind of nonsense. Sarah disapproved of Perry, and told him so, frequently.

“I’ll never understand how they made a daft-like fellow like yon an instructor,” she told David, when she learned they were all instructors. “I wouldn’t trust him to tell a body how to put a key in a lock, never mind fly an aeroplane!”

“Don’t let Perry’s nonsense fool you, Mrs Ramsay,” was the unexpected reply. “He’s just about the best instructor on the camp! Perry’s serious enough when he’s flying.”

At the time Sarah was unconvinced, Perry, she felt, could never be serious.

Soon she became accustomed to R.A.F slang, and they, in turn, pounced delightedly on the more unusual idioms of her north-country tongue and proceeded to work them to death—usually in the wrong places, with hilarious results.

Nina began to look more alive. They treated her like brothers, and she responded to their good-natured teasing like a flower to the sun. The shut-in look left her face, her tongue quickened, and she laughed more readily.

Sarah noticed the change in her, but her thoughts on the matter remained her own.

It was a lonely district and off-duty relaxations were few. The three young men used Greenlaw as a second home, and took joyfully to farm life. Labour was short, and even inexpert help was welcome when it was so whole-hearted. Sarah had to admit that they earned the innumerable meals that she and Nina set down before them.

One after another they were commissioned—Perry first. He preened himself visibly on the evening he walked up and down the kitchen to show off his slim figure to full advantage in all the glory of his new uniform.

“How do I look?”

“Like a bantam cock, my loon,” said Sarah dryly.

“I’ve heard it said that a P.O. is the lowest form of animal life in the R.A.F.” Nina’s eyes were innocent. “Is that true, Perry?”

He delivered a suitably scathing retort, but Sarah never heard it. She was suddenly caught in the memory of another younger and sturdier figure, who had asked exactly the same question when he tried on the new suit she had bought him to go to the university.

It was not until the matter of the Christmas dance that Sarah realised how much difference there was in Nina. It was David who broached the subject.

“You must come,” he declared. “It’s to be a really smashing effort.”

“Satisfaction guaranteed or your money back,” Perry was lolling back in the armchair holding a hank of wool for Sarah.

“Please, Nina,” David said coaxingly. “It’ll be fun—I’m sure you’ll enjoy it.”

“But it’s so—long since I was at a dance.” Her face was wistful. “I’m sure I’ll have forgotten the way how!”

“Bosh!” said Perry. “You never forget how to dance. It’s like riding a bicycle; you just do it again when the time comes! Besides, we’ll make allowances for you—at least I will. It’ll be you that’ll have to make allowances for Dave and Johnnie—don’t say I didn’t warn you!”

“I’d like to come, but—”

“But what?” David’s eyes were as impish as Perry’s. “You’ll have three strings to your bow—what more could a girl ask?”

“If you’re thinking about the four unmentionably bumpy miles that stretch between here and the ‘drome—ignore them! We’ll have a car.” Perry airily dismissed the difficulties.

“Nae bother at ‘a’!” Johnnie remarked unexpectedly, and they all laughed.

“Should I go?” Nina asked Sarah.

“Please yourself.” Sarah would not commit herself, but she was remembering that she was the girl Ian had asked to be his wife, and she wound her ball of wool with increased speed.

In the end, Nina said she would go. It took her a long time to dress, and David and Perry were waiting impatiently for her with the promised car outside before she appeared. Johnnie was still on duty. Then she was in the room, her coat over her arm, and Perry shot out of his chair at the sight of her.

“Guidsakes!” he said, with his best imitation of Sarah.

David said nothing. Sarah turned from the sink and knew that this was the Nina Ian had seen when he fell in love with her.

It wasn’t only that she was using a little make-up or that her corn-coloured hair was brushed out and set so that it swung, shining, to her shoulders, instead of being confined round her head—it wasn’t just that the blue of her shimmering dress frothed round her feet like an opening flower and made her eyes as blue as sapphires. No, it was more than that. It was something in the sparkle of those eyes, in the elusive dimples in the rounded cheeks—something in her smile, and in the vitality that radiated from her. Nina was, for the first time since Sarah had met her, full of excitement and the mere joy of being alive.

Sarah sat alone for a long time after they had left her. Her thoughts were busy, and they were not happy thoughts. It wasn’t fair—it wasn’t right that Ian’s wife should go dancing off into the night with strangers, when Ian’s own brief life was cut off forever! Youth had a short memory, and Nina was like the rest of the young folk.

Sarah was no fool. She had seen the half-incredulous look in David’s brown eyes, the answering smile in Nina’s blue ones, and the tinge of colour in her cheeks. No, her own grief would endure for ever, but the young—they can laugh and forget.

Two days later, Perry arrived alone. His boyish mouth was set in a hard line, and there was a look in his eyes that Sarah had never seen before. He merely came in, took the garage keys from the hook above the dresser and vanished. He brought out the old car and spent nearly three hours cleaning it, working like a beaver.

When he came in again, the hard look was gone from his mouth. Sarah said nothing, and because she didn’t, he told her, confident that she wouldn’t make it unbearable by asking questions.

“I got word this morning. My best pal—crashed on an oil dump. He never had a chance—”

It was when Sarah saw the unprotected look in Perry’s young eyes, she knew by the quick surge of protectiveness she felt towards him, that somehow or other he had slipped into the heart that until then had no room for anybody but Ian.

Periodically they went home on leave, and letters began to come more frequently for Sarah from women she had never seen. Letters, in effect, all said the same thing. Thank you for being so kind to Perry—to David—to “my Johnnie.” That was Pat. She wrote often, and her letters were always liberally sprinkled with “my Johnnie”, and reflected a lightness of heart and an optimism that was lacking in Johnnie’s own outlook at the moment. He was distinctly preoccupied.

It was a letter Perry’s mother sent that Sarah never forgot. The crest that headed the notepaper gave her quite a shock at first, but there isn’t much difference in mothers no matter who they are.

“I can’t thank you enough, Mrs Ramsay, for being so kind to Perry,” she had written. “It is such a relief to me to know that he has somewhere to go where he can feel at home. Perry is my only son, and I don’t have to tell you how much I worry about him. He has told me about your own loss, and I grieve for you. It must be a great consolation to you to have your son’s wife with you. Perry says that she is a charming girl, and I’m sure she must be a great comfort to you. Poor girl, it must be terrible for her. The world belongs to youth, and some of them have so little time to enjoy it—”

Sarah sat over her letter for a long time, and she never forgot these last words. They came back to her the day she overheard a conversation between Nina and David. She did not mean to listen, but they thought she was out and did not lower their voices.

“But don’t you love me at all?” That was David’s voice.

“I do, David. I thought that I would never be able to fall in love with anybody again—but I do love you. Somehow Ian seems like a dream to me now. Only, this doesn’t seem fair to his mother. It’s hard for me to make you understand, David, but she brought me here—a stranger—and gave me nothing but kindness, when I thought that the world had fallen to pieces round about me. Now she depends on me—although she doesn’t realise she does—and she’s got nobody else—”

“But, darling, you must think of yourself, too. You’re only twenty-four—your life is beginning! You’ve got to live. You can’t sacrifice yourself just out of gratitude!”

Sarah had heard enough. She slipped away to her bedroom where she could think. Suddenly she knew that she didn’t want to lose Nina to David—but it wasn’t because Nina was Ian’s wife and she was jealous for his sake. It was because she loved the girl herself, loved her because she was a fine lassie—because Ian had known what he was doing when he chose her for his wife. Greenlaw would be a lonely place without her.

She could hold her, too. She could talk about Ian, as she never had in all the time that Nina had lived with her. She could open her heart to the girl and tell her about Ian who had been first a sturdy child then a mischievous boy, and then the man Nina loved. She could make him live again for Nina so that she would love Greenlaw because it was a part of Ian’s life—could bring him back so vividly that the half-forgotten dream of a few months would become reality again. And Nina would send David away.

She could do all that—but Sarah knew that she never would, because she loved Nina for her own sake, and when you love people, you willingly sacrifice your own happiness for theirs. She would give Nina to David, because David was a nice lad and would make her happy. It was true what Perry’s mother had said. The world belongs to youth—and Nina deserved her share of it.

Perry collected the eggs with her that evening.

“If I ever keep hens, I’ll see to it that they lay in the appointed places!” he commented forcibly, as he scrambled down from the top of the peat stack in the shed and laid a solitary egg in Sarah’s pail.

“There’s nae harm in trying.” There was a glimmer of a smile on Sarah’s face.

They crossed the road and set up off the field.

“Mrs Ramsay—” Perry began, and then paused. It was so seldom Perry’s tongue faltered that Sarah looked at him in surprise. “Johnnie has been wanting to ask you something, but he feels that if he does, it might put you in an awkward position if you really don’t want to do it—refusing would, I mean—so I said I’d mention it first—”

“Guidsakes, laddie—what are ye trying to say?”

“Johnnie’s been hunting all over the district for weeks to find a place for Pat. Naturally, he’s keen to get her away from London just now. He’s had no luck at all—and he wondered if you might let her come here.”

Sarah wasn’t surprised that Johnnie was having difficulty. It would be a responsibility taking the girl when there was to be a baby in two months. Sarah was a realist, and she knew what it would mean if she agreed.

She looked back at Greenlaw, its unlovely lines softened by the glow of the evening sun. There hadn’t been a child born there for twenty-six years. But if she said yes, there would be no turning back. She was an old woman—set in her ways. She might not even like Pat. It would be buying a pig in a poke with a vengeance. Yet, oddly enough, she never hesitated.

“Tell him to ask me himself,” she said.

Perry was carrying the pail, swinging along beside her with the evening sun bright on his hair. Sarah’s heart held an unusual warmth as she looked at him. Time would pass and they would all leave her—Perry and Nina and David and Johnnie and Pat—but she would never really be lonely again.

She didn’t know why she knew it. She just knew that they were all in her heart for ever—beside Ian.

Read previous stories and updates from the podcast.