On this day 80 years ago, the Britain declared war on Germany.

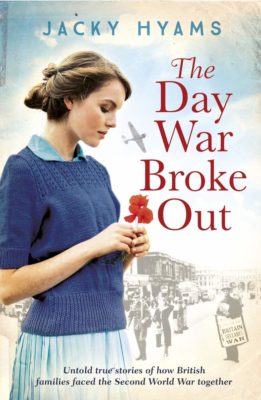

Journalist and author Jacky Hyams has commemorated this event with “The Day War Broke Out”, a book which sheds light on the untold stories of how British families coped with the outbreak of the conflict.

Here, she shares an extract from her work.

My mum and dad were in the midst of the crowd that night near the London Stock Exchange.

A “Daily Express” photographer had been sent out onto the city streets to capture the moment — the instant-reaction shot as the people in the crowd scanned the newspapers.

I have a print of that black-and-white photo hanging on my wall. Mum smiling for the camera amid a sea of men’s suiting; Dad, bespectacled, startled, a bit confused. Twenty-somethings frozen in time, caught up in the historic moment.

The date was 30 September 1938.

“IT IS PEACE”, the headlines screamed, “NO WAR WITH GERMANY”.

Many were already convinced by then that war was imminent.

But on that September night, Britain’s Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, had flown back from Munich after his third meeting with German Chancellor Adolf Hitler.

A last chance for peace

He was waving an important piece of paper: a nonaggression pact with Germany. Hitler had been readying to invade Czechoslovakia. Now, thanks to Chamberlain’s diplomatic efforts, he had agreed to desist.

The bit of paper, the PM told the cheering crowds, “was symbolic of the desire of our two peoples never to go to war with each other again”.

“Peace for our time,” he said that night.

“Yes, but how long is ‘our time’?” came the cynical response.

Perhaps understandably, some people clung to the hope that this was genuine. Here was a last chance for peace.

Others who had watched events in Germany in the previous few years with growing alarm saw the Munich fiasco for what it was: a last-ditch diplomatic attempt to stave off the inevitable; a way of buying urgently needed time for both sides to prepare for war.

Germany had openly rearmed while Britain’s defences were in a parlous state.

iStock.

Preparations and planning for war, a shade too tentative until then, would now have to be accelerated with all speed.

In July 1939, the Civil Defence Act enabled faster progress to be made in the implementation of many wartime plans.

Employers with more than thirty workers were now required to organise ARP training, while those with a workforce of more than fifty based in a large city or danger area had to provide a form of air-raid shelter for their employees.

By August, the annual British holiday season had been completely overshadowed by the threat of war.

Naturally, families hesitated about heading off to the seaside or to country beauty spots in this situation.

But for many people, common sense prevailed.

“Well, it might be our last good holiday before war breaks out,” they thought, so they opted to take the holiday.

Getting ready for war

The announcement that petrol would be rationed if war broke out was a sobering reality check, though.

In the early morning of 1 September 1939, under cover of darkness, German troops marched into Poland.

Within hours, the capital, Warsaw, was being bombed. That same day, the planned evacuation of thousands of mothers and children from British cities began.

iStock.

Toddlers clutching tiny cases and gas masks, with luggage labels pinned to their lapels, boarded buses, trains and — in some cases — boats, to make their way to the safety of the countryside, waved off by anxious parents.

Photographs of these partings appeared in all the mass-circulation newspapers, creating a positive sense that the country was protecting its most vulnerable.

That night, two days before Britain’s formal declaration of war, the blackout went into effect throughout the country. Many cinemas, theatres, clubs and places of entertainment were closed. (Most would, in fact, reopen after the declaration of war.)

Television broadcasting was shut down – the government was concerned that the VHF transmissions would act as a beacon for enemy aircraft homing in on London.

In fact, in 1939, very few owned a television set — around 20,000 in London — but those who were watching discovered in the middle of a programme that the signal had been switched off, without warning.

It would not be switched back on again until 1946.

An entire nation held its breath – and waited.

You can buy Jacky’s book in bookshops and online in paperback, published by John Blake, RRP £8.99.

Our Archives offer some glimpses into the homefront during the both World Wars, including reader correspondence and even recipes making the most of rationing.