This is part two of “Major Cameron’s Wife” by M.C. Ramsay, first published in “The People’s Friend” in 1915.

If you missed part one, click here.

Marjory’s next letter was written from sunny Southern France. It was longer than any which had preceded it, for it told him of the persistent rumours that war between France and Germany was an almost inevitable thing, and that Britain would more than likely be forced in too.

Before the letter reached him, the war-clouds had burst, and his first thought was —

“I hope Marjory and her people have got safely home. It would kill her to see the awful horrors of war!”

Never for a single moment did he imagine that his pretty, doll-like, helpless wife had defied parents and friends, refused to accompany them home, volunteered for Red Cross Service in France, and had been accepted the more gladly because she could speak both German and French.

And even as Dick was reading her letter, she was living through scenes of horror which might well have driven a stronger-minded woman mad.

But Marjory Cameron did her work unflinchingly, her one desire to relieve the sufferings of the brave men entrusted to her care. Her most secret thought —

“I know Dick would approve if he knew! But, oh, though I know it is cowardly, yet I cannot but feel thankful that Dick, as an officer in a native regiment, will not be sent to the Front.

“It—it would kill me if I had constant dread and fear for him.”

Yet only a few days later, the clever French surgeon who openly showed his admiration of the brave young Scotswoman, uttered words which sent the colour flying from her cheeks.

“Have you heard the latest, Mrs Cameron? The Kaiser has got another bitter disappointment! India was to rise en masse, and throw off the hated British yoke.

“Instead, every Indian Prince has offered his personal services, his men, his gold! And it has been decided that picked Indian troops will play their part in the great struggle — some are, indeed it is said, already on their way!”

“You do not know what regiments?” Marjory faltered.

Dr Le Feuvre shook his head.

“No. That is one of the secrets of your wonderful Kitchener of Khartoum. I fear the news does not please you?”

“Yes, oh, yes,” said Marjory hastily. “I know what our gallant Indian troops can do. My husband is an officer in a native regiment, and I—I can be strong and brave for myself, but not for him!”

The surgeon laid his hand on her shoulder.

“I understand, Madame,” he said gently, “yet I know you would not keep him back if you could.” And to her own surprise Marjory answered emphatically —

“No, oh no! I have learned many things in these past weeks — but nothing more certain than this, that the Daughters of the Empire must give of their best and dearest without grudge if the Right is to prevail!”

Dick’s heart would indeed have thrilled with pride if he could have seen and heard her then.

He was writing at that moment to tell her his glorious news — that his regiment was ordered to the Front, that the men were wild with joy!

“The unswerving loyalty of India and the Colonies is the most wonderful bit of it all,” he wrote. “Won’t you try now, dearest, to understand my passionate attachment to the regiment, to believe, at the same time, that it never filled the place belonging of right to you!

“I am going forth to face death. I cannot do so without telling you that I love you with my whole heart and soul!

“It would strengthen me for what lies before me if I found a note with but the one message, ‘Dick, I love you,’ awaiting me when we set foot on French soil!”

That letter duly reached Marjory’s Scottish home, but went astray on its journey to France.

And, when his regiment reached Marseilles, Dick looked in vain for the message she would so gladly have sent.

He only set his teeth the harder, and thanked God that one thing was left him — to fight — he hoped to die! — for the old Flag.

What was there to live for now that he had received this absolute proof that Marjory had entirely ceased to care!

Until then he had hoped against hope that some sparks of the old love still slumbered in the grey ashes, that he knowledge of his danger would fan them into flame.

Now hope was dead and his heart and his emotions alike seemed to have died with it.

Nothing could move him. Even their wonderful reception by the French populace — who hailed them as deliverers, showered gifts upon them, strewed their path with flowers —had no power to stir him.

His one conscious desire was to get away from the excited, cheering, weeping, laughing crowds, into the fighting line. If Death awaited him there, so much the better, for thus only could Marjory be freed from the hated bondage of her marriage to him.

And all the while Marjory was praying that the line of march would bring him though the town where she was doing her part so nobly and so bravely, that they might see each other though it were for but a moment.

One glance into his face would tell her if his love for her were indeed dead.

There came a morning when that prayer was partially answered.

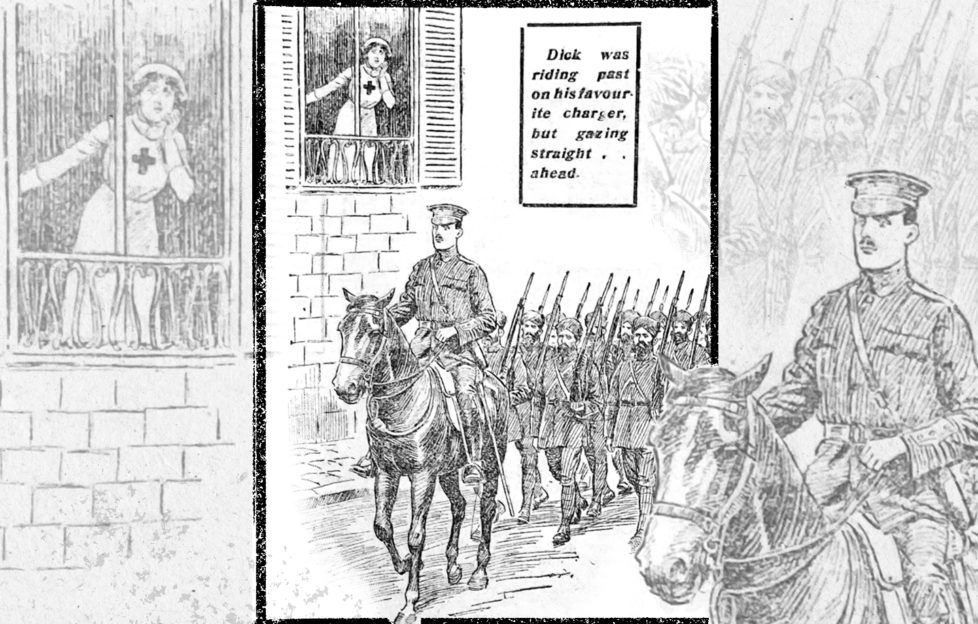

The surgeon had finished his round of her ward — a big room of a fashionable summer hotel now turned into a house of pain — and before passing out, he glanced from a window which looked down into the street.

The next moment he had called her name.

“Nurse Marjory, the Indian troops!”

On the instant she was by his side, white to the very lips. Her hand caught his arm, and closed convulsively around it.

Dick was riding past on his favourite charger, but gazing straight ahead. With all her strength, she willed that he would look up. He did not.

In her high strung state, this seemed proof positive that he did not care.

“If he loved me, he would know by instinct that I was near,” she thought, with all a true woman’s lack of reason. “But now, as always, the regiment is his first thought.”

At the same time she felt a strange thrill of pride as the warriors marched past. Had not his Colonel told her that the regiment owed more to Dick than to any other living man?

“It has been father, mother, wife, and child to him until you came,” the old Colonel had said.

“Don’t make the mistake of being jealous of it — of trying to wean him from it as some foolish women would do!”

Yet that was what she had done. She knew it now. She had rightly failed. Her punishment was no greater than she deserved.

The windows of the house opposite were crowded. A young girl suddenly leant out and tossed a great bunch of white La France roses to the grave-faced man on the big brown horse.

Instinctively Dick caught it, then with a exclamation of pain let it drop.

“Roses just like these formed my wedding bouquet. I suppose he can’t bear the look of them now!” And much that had puzzled the doctor became plain, yet he was too wise to give her any answer then.

The last company was passing. The senior subaltern — a happy-go-lucky boy with whom Marjory had flirted light-heartedly during her Indian year, stooped and lifted the roses which had escaped destruction as by a miracle.

He glanced towards the great building above which the Red Cross floated. He saw a nurse fling wide a window. He heard his name called —

“Harry! Harry Carnegie! Give them to me!”

And as he tossed the flowers towards her, a radiant smile lit up his frank, open, sun-browned face.

“By Jove, that’s the queerest thing I’ve seen since I came here,” he murmured to himself. “Mrs Cameron a Red Cross nurse! And a hundred times more beautiful than before. I wonder if the Major does not know!”

Then he, too, passed out of her sight, and Marjory was left behind, clutching the roses which Dick had flung from him as if he had been stung.

A long thorn pierced her delicate flesh, drawing blood. She did not feel it, because of the pain at her heart.

A wounded young French officer called to her. He wanted to know what troops had passed.

When she told him, he feebly raised a cheer.

Nurse Marjory’s smiles gave little sign of her breaking heart. He glanced at the roses. She placed them in a bowl on a table near his bed.

His lips quivered.

“They grow in hundreds in the old garden at home,” he whispered. “My Felicie should have been carrying them as a bridal bouquet this very day!”

Hastily Marjory turned aside. She felt that she could endure no more.

To be concluded next week.

Click here to read more of our fantastic Fiction content.

Click here to delve into our dramatic Daily Serial.