On Your Bike Flying High

Hildy didn't want anyone's help to make her dream come true...

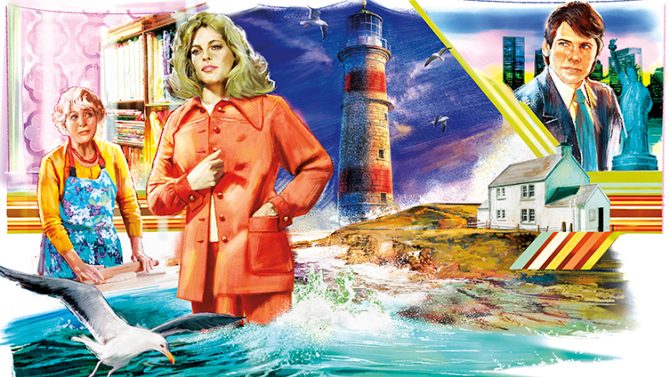

Illustration: David Young

Subscribe to The People’s Friend! Click here

Hildy didn't want anyone's help to make her dream come true...

Illustration: David Young

HISTORICAL SHORT STORY BY PAMELA ORMONDROYD

In this story, set in the 1890s, Hildy didn’t want anyone’s help to make her dream come true…

Mam, mam! Come quick! Our Hildy’s riding a bicycle.”

Norah Schofield stopped rolling out her pastry and sighed. It had taken over an hour to settle the baby and, already weary, she had just begun preparing a meat pie for the evening meal.

“Stop your shouting, Agnes! Can’t you see I’m busy?”

“It’s true, Mam,” five-year-old Agnes said as she pulled on her mother’s sleeve. “Hildy’s on a bicycle! I just saw her. Wobbling all over, she is.”

Norah wiped her hands on her apron and jostled her younger daughter into the front parlour where the door to the street was already wide open.

Cheers and laughter sounded from the factory end and, as she stepped out on to the pavement, she saw her older daughter weaving and twisting all over the road on a machine that was far too big for her.

There was no mistaking that mass of copper-coloured curls.

Norah put her hand to her mouth. Hildy was an accident just waiting to happen.

“Mind the baby, Agnes,” she said, and then she flew along the road as fast as her legs could carry her.

She could hardly bear to look as her feisty daughter took one hand off the handlebar and waved wildly to her audience as if she was a circus act.

And then a second later, both the girl and the bike were lying in the gutter, the wheels still spinning rapidly.

Hildy lay splayed out in a most undignified fashion, while a tall boy in a cap ran over to help.

At least she was still grinning and didn’t look badly hurt apart from a huge hole in her stockings and a grazed knee.

“Honestly, Hildy Schofield,” Norah said.

You’ve made a real exhibition of yourself this time, haven’t you?

Hildy sat up and shrugged her shoulders.

“Come on, home with you. Let’s get you cleaned up.” Then Norah turned to the boy in the cap who had now retrieved his bicycle and was checking it over.

“And as for you, Archie Slack, you should know better than to encourage a girl to ride a dangerous butcher’s bike when she has no sense of direction at all.”

“I didn’t encourage her, Mrs Schofield,” the eighteen-year-old delivery boy replied, looking peeved.

“She took it from in front of my uncle’s shop.” He held out a hand to Hildy and eased her up.

“And if it’s been damaged, I know who will be getting the bill.”

“That bicycle shouldn’t be on the road,” Hildy mumbled.

“The brakes don’t work for one thing.”

“Don’t give me that, Miss High and Mighty. I could have you arrested for theft.”

“Now, now, you two,” Norah said as she stepped between the warring pair.

“Let’s not get all het up, eh?

“I reckon this daughter of mine has learned a hard lesson. She won’t do it again, Archie.” She took Hildy’s arm and glared at her.

But Hildy wasn’t finished yet.

“So, where’s my sixpence, Archie Slack?” she yelled back as Norah led her down the street.

“You bet me sixpence I couldn’t ride your precious machine!”

“Well, you couldn’t!” Archie shouted, looking surprised at her audacity. “You fell off!”

“Not before I rode it for a full five minutes. I’ve got witnesses.”

“Oh, just get in the house before I lose my patience,” Norah said as she pushed her errant daughter through the front door, where she found Agnes, trying to soothe a red-faced infant.

”You’ve woken the baby up now.”

As the door slammed shut, Archie Slack picked up his bike and a broad smile spread over his face.

The following week at the cotton mill, all Hildy could think of was owning a bicycle: a magical two-wheeled machine that would pluck her from the drudgery of the factory and the

grimy, smoky terraced streets and transport her to places she had only ever seen in old school books.

She pictured green meadows full of wild flowers, rolling hills and country lanes leading down to the open sea.

It was all there waiting for her to explore if only she had a bicycle – her passport to freedom, where she could fly like a bird.

Then there were the practicalities of how she could make her dream happen.

How would she ever have the means to acquire such a machine?

Her wage of six shillings went nowhere when she handed over five of them to her mother for her keep.

The little she could save would take her years.

She was still trying to think of a way she might raise some extra cash when she felt a hard tap on her shoulder and turned to see one of the mill women, Rachel Slack, Archie’s older sister.

“Are you doing this on purpose, Hildy Schofield?” Her face was grim and she looked angry.”

“Oh, I’m sorry,” Hildy said, coming back to earth with a bump and handing over the new bobbin.

The noise from the looms was horrendous – it was hard to hear anyone speak, so all the women in the shed had learned to lip read.

“Are you being deliberately slow to get your own back after your spat with Archie?

You know time means money in this place and I can’t afford to lose a single penny.

“Nor can you, miss, what with your father on short time and five mouths to feed, so just pull yourself together, will you?”

“Yes, all right. I said I’m sorry and it won’t happen again.” Yet in her heart, Hildy knew it probably would.

She hated the factory, the constant racket, the dust balls that stuck in your throat, the daily predictable grind.

The sooner she got out of this place, the better!

When she got home, her father was sitting in his chair, lighting his pipe.

He was a quiet, affable man, a contrast to Norah who was more vocal and constantly fussing.

“Good week, our Hildy?” her father asked as she strode wearily through the front door.

“No more causing chaos with the butcher’s bicycle then?” He chuckled.

“Oh, don’t encourage the lass, Samuel,” Norah scolded as she laid the table.

“We don’t want any more talk of bicycles in this house, I’ll thank you.

“Those contraptions are only for them ladies of leisure with more money and time on their hands than sense.

“Hildy, go and give the stew a stir then fetch Agnes and the baby from the back alley.

“I gave her a halfpenny to mind him for an hour or so and she’s done well.

“Oh and put your wages in the tin, will you? The rent man will be round later.”

Hildy went into the scullery to wash her hands, wanting to scream.

Why was everyone always so demanding of her? She was only seventeen, for goodness’ sake.

She did her best, paid her way. Surely she should be able to have a little fun sometimes?

Later, when the younger ones were in bed, Hildy sat on the rug in front of the fire and read the paper to her father.

Samuel Schofield had spent such a long time down the mine that his eyesight was failing and reading the small print was an effort.

Hildy picked out local news and stories that she thought might interest him, and as his eyes slowly closed, she flicked through the remaining pages for her own entertainment.

An article grabbed her attention.

She had almost forgotten that Briarsfield held a large Sunday market in the square in front of the town hall.

She hadn’t been over that way for ages since the market was on the other side of town, a good two-mile walk each way.

And not a particularly pleasant walk at that, since the only route was through the poorest streets of town.

But an idea had begun to form in her head.

If she got over there early on Sunday morning, it was possible she might be able to find temporary employment on one of the stalls

Of course, it meant that she would be giving up her only day off in the week, but it would be worth it.

She would be able to keep any money earned for herself and her dream of owning a bicycle might just be a little closer to reality.

“I don’t know what you’re thinking of, going all that way on your one day off,” Norah said the following morning, as Hildy tied her apron strings and wrapped up a piece of bread and cheese for her lunch.

“I’ll be back just after lunch, Mother,” Hildy said impatiently.

The morning was chilly and the sky full of grey clouds but at least it was dry.

Hildy walked along the streets towards the town centre, noting the squalid conditions that some poor folk were forced to live in – the overcrowding, the poor lighting, the litter in the alleyways.

She had heard that at night some parts were notoriously crime-ridden and she felt grateful that at least she was walking in daylight.

The two miles seemed to take an age, but as she got nearer to the town hall, she saw the market was already up and running.

And what a bustling, joyous place it was.

Hildy was greeted by colourful bunting and lots of chatter and clatter as the square seemed to take on a life of its own.

Everything she could imagine was laid out tidily to attract the buyers –vegetables, bread and cakes, meat, flowers, crockery, haberdashery, even gleaming bicycles.

Buskers were claiming their pitches, the organ grinder was turning his handle, acrobats and other street entertainers were warming up.

Hildy enjoyed just taking it all in before she began to do the rounds and offer her services.

At first, she was greeted by negativity.

No-one needed any help – at least, not help they would have to pay for.

The lady on the wool stall was very nice and apologetic, while another one selling biscuits wished her luck.

But Hildy was undeterred and finally, as she reached the far end of the market, she struck gold!

A grumpy man selling soup and sandwiches said he had been let down that particular morning and was prepared to give her a trial.

I’ll give you sixpence if you prove your worth, young woman

he said.

“Can’t afford nothing more. You’ll need to be quick and efficient.”

If Hildy made a good a good impression, there was every chance she might secure a regular position and maybe even a pay rise!

The morning was hectic, though.

Despite the dull day, the market was well attended, and because of the chill, the hot broth proved very popular.

Hildy didn’t stop. If she wasn’t serving on the outside tables, she was wiping them or washing crockery behind the stall.

Just after midday things slowed down, and by early afternoon, as people began to disperse and the market packed up, Hildy had not just a sixpence but an extra threepenny bit in her apron pocket.

“Come back next week,” the man said, a little more friendly now, apparently recognising a good worker when he saw one.

Feeling pleased, Hildy nodded and started on her journey back home. The early start had been worth it after all.

But just as she crossed the road the heavens opened. Hildy had no umbrella, nor even a decent jacket, and she was suddenly aware of how much her feet were stinging.

She looked down at her shoddy boots, aware that there were holes in both heels which were already letting in water.

There was nothing for it but to hurry on home.

After half a mile, her hair was sopping and the rain was trickling down her neck.

She untied her apron to use as a head scarf, forgetting that she had put her wages in the pocket, and the next thing she saw through the horizontal rain was a silver sixpence fall to the ground and then slip through the grate in the gutter to be lost for ever.

She put her hand in her pocket to check that at least the threepenny bit was still there and went to sit in an empty bus shelter, angry and upset that she could have been so stupid.

“Hildy! I thought it was you. What are you doing out here?”

She looked up and there before her, red faced and sopping wet, was Archie Slack and his bicycle.

Immediately, Hildy went on the defensive. How dare he find her when she was so compromised.

“I’ve been working,” she said. “On the market. I’ve got a permanent job there, if you must know.”

“I’ve been there, too,” Archie said, leaning his bicycle against a wall and joining her.

“I sometimes help my uncle with his meat stall on a Sunday.”

He moved closer to her and she stood up and shook her wet hair.

“It’s eased off a bit now,” she said, pushing past him. “So I’ll make a dash for it.”

“What! In those boots of yours, Hildy? You’ll never make it to the end of the road.

“Come on, I’ll give you a lift on the bike.”

“No, thank you. I’d rather walk. Barefoot if I have to. I’ve done it before.”

He’d caught her when she was at her most vulnerable. But she wouldn’t back down.

“Look, Hildy, no-one will see you with me, not on a day like this.

“And I won’t tell anyone if that’s what you’re worried about. I just want to help.”

The pain in her right foot was awful. She had a blister, she was sure of it.

“All right,” she conceded. “Just this once, mind.”

Archie nodded and a wry smile spread over his face.

He helped her up on to his saddle, threw her boots into the basket on the front and then got astride himself.

He pushed off from the kerb and, standing upright and pedalling as fast as he could, took her home.

Hildy held on to his jacket, and as he pedalled faster, she hung on more tightly.

Then the emotion of the morning got to her and, tired and cold, she laid her head on his shoulder and her silent tears melted into the rain.

The following morning, Hildy was rudely woken by the six a.m. factory hooter. She rolled out of bed and as her feet touched the cold floor she winced with pain.

Then she realised that her boots were still in Archie’s basket and her heart sank. She had no other pair.

How on earth would she be able to work barefoot?

She would have to feign sickness. She hurried downstairs to catch some of the other girls in the street who were already rushing to work.

She opened the front door and there on the step sat a pair of polished, mended, good-as-new black boots. She stooped down and picked them up.

They were hers; she would know them anywhere.

Then she looked across the street and, lurking in the alley, she saw Archie Slack.

He must have had them mended, and was waiting to make sure she found them.

But why would he do such a thing, when she was always so spiteful towards him?

Hildy slipped her feet inside and, pulling her shawl about her, ran across the road.

Archie drew back into the shadow of the alley as she approached.

“Archie, I don’t understand. Why are you being kind to me? I’ll pay you back. Every penny.”

“I don’t want your money,”

Never miss an issue ‘The People’s Friend’ packed with even more stories on sale every Wednesday.

Paula Williams

Deborah Siepmann

Alison Carter

Teresa Ashby

Beth Watson

Alyson Hilbourne

Katie Ashmore

Kate Hogan

Liz Filleul

Beth Watson