Shutterstock / antoniradso©

Shutterstock / antoniradso©Did you read this week about the plan to raise the wireless equipment Harold Bride and Jack Phillips famously used to call for help as the RMS Titanic was sinking?

Apparently the coronavirus pandemic has put paid to that idea for the moment.

It reminded me of this article I found in the DC Thomson Archives. It was first published in May 1912, just one month after the disaster.

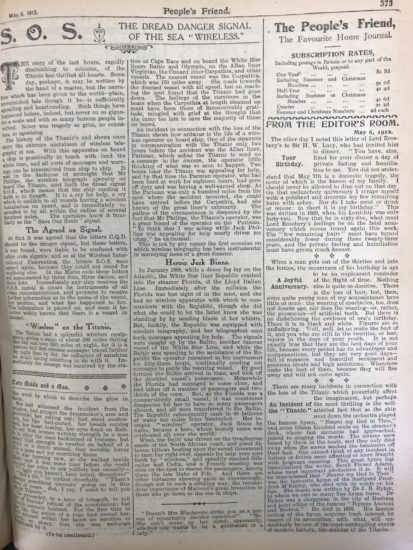

S.O.S. The Dread Danger Signal Of The Sea Wireless

The story of the last hours, rapidly diminishing to minutes, of the Titanic has thrilled all hearts.

Some day, perhaps, it may be written by the hand of a master. But the narrative which has been given to the world — plain, unvarnished tale though it be — us sufficiently appalling and heartrending.

Such things have happened before, indeed, but never on so gigantic a scale and with so many famous people involved.

Never was a tragedy so grim, so relentless, so agonising.

The history of the Titanic’s end shows once more the extreme usefulness of wireless telegraphy at sea. With this apparatus on board a ship is practically in touch with land the whole time. All sorts of messages and warnings can be transmitted from ship to ship.

It was in the darkness of midnight that Mr Phillips, the wireless telegraph operator on board the Titanic, sent forth the dread signal S.O.S. which means that the ship sending it forth is in danger.

It is a cry for help. A cry which is audible to all vessels having a wireless installation on board, and is immediately responded to by all within the radius of several hundred miles.

The operators know it familiarly as the “Save Our Souls” signal.

The Agreed On Signal

At first it was agreed that the letters C.Q.D. should be the danger signal. But these letters, it was found, were liable to be confused with other code signals.

And so at the Wireless International Convention the letters S.O.S. were agreed upon.

In the Morse code these letters are represented be three dots, three dashes, and three dots. Immediately any ship receives the S.O.S. signal it clears its instruments of all other communications. They prepare to receive further information.

The information is passed on, and soon it becomes widely known that there is a vessel in danger.

“Wireless” On The Titanic

The Titanic had a splendid wireless equipment, giving a range of about 500 miles during the day and over 1000 miles at night. For it is a curious fact that wireless messages travel farther by night than by day.

Immediately the message was received by the station at Cape Race. Also on board the White Star liners Baltic and Olympic, on the Allan liner Virginian, the Cunard liner Carpathia, and other vessels.

The nearest vessel was the Carpathia, which was 170 miles away. She made towards the doomed vessel with all speed.

But on reaching the spot found that the Titanic had gone down.

The feelings of the survivors in the boats when the Carpathia at length steamed up must have been those of inconceivable gratitude. But mingled with grief at the thought that she came too late to save the majority of those on board.

She could have arrived before the Carpathia

An incident in connection with the loss of the Titanic shows how arduous is the life of a wireless operator on board ship.

One of the steamers in communication with the Titanic only two hours before the accident was the Allan liner, Parisian. She had asked the Titanic to send on a message to the owners, the operator little thinking of what was soon to happen.

Two hours later the Titanic was appealing for help. And by that time the Parisian operator, who had been hard at work for eighteen hours, had gone off duty.

The Parisian was only a hundred miles from the spot where the accident occurred. She could have arrived before the Carpathia, had she known of the great liner’s extremity.

The pathos of the circumstance is deepened by the fact that Mr Phillips, the Titanic’s operator, was a great friend of the operator on the Parisian.

“To think that I was asleep while Jack Phillips was appealing for help nearly drives me crazy,” he exclaimed.

This is not by any means the first occasion on which wireless telegraphy has been instrumental in conveying news of a great disaster.

This is just one of the fascinating things I’ve discovered in the Archives while researching stories for “Reading Between The Lines”, our story podcast.

You can hear those stories by subscribing to the podcast. The next episode is out tomorrow!